XXX . V Financial Institutions and Customer Information: Complying with the Safeguards Rule

Many companies collect personal information from their customers, including names, addresses, and phone numbers; bank and credit card account numbers; income and credit histories; and Social Security numbers. The Gramm-Leach-Bliley (GLB) Act requires companies defined under the law as “financial institutions” to ensure the security and confidentiality of this type of information. As part of its implementation of the GLB Act, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) issued the Safeguards Rule, which requires financial institutions under FTC jurisdiction to have measures in place to keep customer information secure. But safeguarding customer information isn’t just the law. It also makes good business sense. When you show customers you care about the security of their personal information, you increase their confidence in your company. The Rule is available at ftc.gov.

Who Must Comply?

The definition of “financial institution” includes many businesses that may not normally describe themselves that way. In fact, the Rule applies to all businesses, regardless of size, that are “significantly engaged” in providing financial products or services. This includes, for example, check-cashing businesses, payday lenders, mortgage brokers, nonbank lenders, personal property or real estate appraisers, professional tax preparers, and courier services. The Safeguards Rule also applies to companies like credit reporting agencies and ATM operators that receive information about the customers of other financial institutions. In addition to developing their own safeguards, companies covered by the Rule are responsible for taking steps to ensure that their affiliates and service providers safeguard customer information in their care.For more information on whether the Safeguards Rule applies to your company, consult section 313.3(k) of the GLB Privacy Rule and the Financial Activities Regulations. Both are available at www.ftc.gov/enforcement/rules/rulemaking-regulatory-reform-proceedings/privacy-consumer-financial-information.

How To Comply

The Safeguards Rule requires companies to develop a written information security plan that describes their program to protect customer information. The plan must be appropriate to the company’s size and complexity, the nature and scope of its activities, and the sensitivity of the customer information it handles. As part of its plan, each company must:- designate one or more employees to coordinate its information security program;

- identify and assess the risks to customer information in each relevant area of the company’s operation, and evaluate the effectiveness of the current safeguards for controlling these risks;

- design and implement a safeguards program, and regularly monitor and test it;

- select service providers that can maintain appropriate safeguards, make sure your contract requires them to maintain safeguards, and oversee their handling of customer information; and

- evaluate and adjust the program in light of relevant circumstances, including changes in the firm’s business or operations, or the results of security testing and monitoring.

Securing Information

The Safeguards Rule requires companies to assess and address the risks to customer information in all areas of their operation, including three areas that are particularly important to information security: Employee Management and Training; Information Systems; and Detecting and Managing System Failures. One of the early steps companies should take is to determine what information they are collecting and storing, and whether they have a business need to do so. You can reduce the risks to customer information if you know what you have and keep only what you need.Depending on the nature of their business operations, firms should consider implementing the following practices:

Employee Management and Training. The success of your information security plan depends largely on the employees who implement it. Consider:

- Checking references or doing background checks before hiring employees who will have access to customer information.

- Asking every new employee to sign an agreement to follow your company’s confidentiality and security standards for handling customer information.

- Limiting access to customer information to employees who have a business reason to see it. For example, give employees who respond to customer inquiries access to customer files, but only to the extent they need it to do their jobs.

- Controlling access to sensitive information by requiring employees to use “strong” passwords that must be changed on a regular basis. (Tough-to-crack passwords require the use of at least six characters, upper- and lower-case letters, and a combination of letters, numbers, and symbols.)

- Using password-activated screen savers to lock employee computers after a period of inactivity.

- Developing policies for appropriate use and protection of laptops, PDAs, cell phones, or other mobile devices. For example, make sure employees store these devices in a secure place when not in use. Also, consider that customer information in encrypted files will be better protected in case of theft of such a device.

- Training employees to take basic steps to maintain the security, confidentiality, and integrity of customer information, including:

- Locking rooms and file cabinets where records are kept;

- Not sharing or openly posting employee passwords in work areas;

- Encrypting sensitive customer information when it is transmitted electronically via public networks;

- Referring calls or other requests for customer information to designated individuals who have been trained in how your company safeguards personal data; and

- Reporting suspicious attempts to obtain customer information to designated personnel.

- Regularly reminding all employees of your company’s policy — and the legal requirement — to keep customer information secure and confidential. For example, consider posting reminders about their responsibility for security in areas where customer information is stored, like file rooms.

- Developing policies for employees who telecommute. For example, consider whether or how employees should be allowed to keep or access customer data at home. Also, require employees who use personal computers to store or access customer data to use protections against viruses, spyware, and other unauthorized intrusions.

- Imposing disciplinary measures for security policy violations.

- Preventing terminated employees from accessing customer information by immediately deactivating their passwords and user names and taking other appropriate measures.

Information Systems. Information systems include network and software design, and information processing, storage, transmission, retrieval, and disposal. Here are some suggestions on maintaining security throughout the life cycle of customer information, from data entry to data disposal: - Know where sensitive customer information is stored and store it securely. Make sure only authorized employees have access. For example:

- Ensure that storage areas are protected against destruction or damage from physical hazards, like fire or floods.

- Store records in a room or cabinet that is locked when unattended.

- When customer information is stored on a server or other computer, ensure that the computer is accessible only with a “strong” password and is kept in a physically-secure area.

- Where possible, avoid storing sensitive customer data on a computer with an Internet connection.

- Maintain secure backup records and keep archived data secure by storing it off-line and in a physically-secure area.

- Maintain a careful inventory of your company’s computers and any other equipment on which customer information may be stored.

- Take steps to ensure the secure transmission of customer information. For example:

- When you transmit credit card information or other sensitive financial data, use a Secure Sockets Layer (SSL) or other secure connection, so that the information is protected in transit.

- If you collect information online directly from customers, make secure transmission automatic. Caution customers against transmitting sensitive data, like account numbers, via email or in response to an unsolicited email or pop-up message.

- If you must transmit sensitive data by email over the Internet, be sure to encrypt the data.

- Dispose of customer information in a secure way and, where applicable, consistent with the FTC’s Disposal Rule. For example:

- Consider designating or hiring a records retention manager to supervise the disposal of records containing customer information. If you hire an outside disposal company, conduct due diligence beforehand by checking references or requiring that the company be certified by a recognized industry group.

- Burn, pulverize, or shred papers containing customer information so that the information cannot be read or reconstructed.

- Destroy or erase data when disposing of computers, disks, CDs, magnetic tapes, hard drives, laptops, PDAs, cell phones, or any other electronic media or hardware containing customer information.

Detecting and Managing System Failures. Effective security management requires your company to deter, detect, and defend against security breaches. That means taking reasonable steps to prevent attacks, quickly diagnosing a security incident, and having a plan in place for responding effectively. Consider implementing the following procedures:

- Monitoring the websites of your software vendors and reading relevant industry publications for news about emerging threats and available defenses.

- Maintaining up-to-date and appropriate programs and controls to prevent unauthorized access to customer information. Be sure to:

- check with software vendors regularly to get and install patches that resolve software vulnerabilities;

- use anti-virus and anti-spyware software that updates automatically;

- maintain up-to-date firewalls, particularly if you use a broadband Internet connection or allow employees to connect to your network from home or other off-site locations;

- regularly ensure that ports not used for your business are closed; and

- promptly pass along information and instructions to employees regarding any new security risks or possible breaches.

- Using appropriate oversight or audit procedures to detect the improper disclosure or theft of customer information. It’s wise to:

- keep logs of activity on your network and monitor them for signs of unauthorized access to customer information;

- use an up-to-date intrusion detection system to alert you of attacks;

- monitor both in- and out-bound transfers of information for indications of a compromise, such as unexpectedly large amounts of data being transmitted from your system to an unknown user; and

- insert a dummy account into each of your customer lists and monitor the account to detect any unauthorized contacts or charges.

- Taking steps to preserve the security, confidentiality, and integrity of customer information in the event of a breach. If a breach occurs:

- take immediate action to secure any information that has or may have been compromised. For example, if a computer connected to the Internet is compromised, disconnect the computer from the Internet;

- preserve and review files or programs that may reveal how the breach occurred; and

- if feasible and appropriate, bring in security professionals to help assess the breach as soon as possible.

- Considering notifying consumers, law enforcement, and/or businesses in the event of a security breach. For example:

- notify consumers if their personal information is subject to a breach that poses a significant risk of identity theft or related harm;

- notify law enforcement if the breach may involve criminal activity or there is evidence that the breach has resulted in identity theft or related harm;

- notify the credit bureaus and other businesses that may be affected by the breach.

- check to see if breach notification is required under applicable state law.

XXX . V0 Are you prepared for an e-audit?

Electronic data processing audits, also called “e-audits,” generally have two objectives:

(1) to review the organization’s computer and information systems to evaluate the integrity of its production systems and potential security weaknesses;

and (2) to undertake a tax audit based on data analytics.

How can you anticipate and prepare? Not only should you be aware of legal obligations required for each country where you do business and in what format, you should also consider the demands that e-audits could place on your systems and operations.

Ultimately, you may need to change the way you record, store and retrieve your information for VAT/GST. You may even need to change the way you manage VAT/GST within your organization.

Seven leading practices for preparing e-audits

1. Identify your VAT/GST data The VAT/GST information needed for most e-audits includes details from customer, supplier and product databases. And don’t forget items such as the algorithm for attributing VAT/GST codes.

2. Determine which VAT/GST details are required

What do the tax authorities in each country require, and how and when do they require it? Knowing the scope of e-audit legislation can help you to comply more effectively with each authority’s requests. It can also prevent you from providing more data to the tax administration than is required by law.

3. Collaborate across your business

VAT/GST data generally consists of large amounts of accounting and management information, spread throughout the ERP or IT systems. In most organizations, designing effective systems and processes to collect, store and retrieve the VAT/GST information needed for an e-audit means involving several specialist functions, including tax, finance and IT.

4. Create a methodology for storing your VAT/GST data

Most e-audits are difficult to manage because the data is not readily available. Data storage periods differ from country to country — as do the rules related to how and where you may store data (for example, online or on paper).

What are the best ways for you to store data long term? Is the solution sustainable and cost-effective? Weigh up the costs and benefits of using the standard SAF-T audit file methodology.

5. Establish how to retrieve and deliver your data

The exact data points requested, the time frame for providing the information or the data format itself may differ from country to country. You must be able to retrieve the data requested on time and in the right format. You may need to identify specific tools for large data sets.

This information is often requested by the tax administration at the start of the e-audit. Delays in producing it can cause disruption, and even penalties and fines. Take these factors into account in considering the costs and benefits of using the OECD standard SAF-T.

6. Understand the checks that e-auditors apply

What are the tax authorities likely to look for in your data? Do you know what they might find? Anticipate the outcome of an e-audit by examining the VAT/GST data that the tax auditors will be given, using the same tools.

By conducting an internal audit before an e-audit is announced, you may avoid unexpected tax adjustments and reduce or even avoid tax penalties.

7. Use e-audit techniques to manage VAT/GST better

Improve your ongoing VAT/GST compliance by using the data analytics software and validations that tax auditors commonly employ. Incorporating these checks into your regular VAT/GST control processes can greatly reduce tax risk by allowing you to remedy errors and weaknesses as they occur. It can also help to identify areas where the tax law or treatment of your activities needs to be clarified, ahead of your next e-audit.

Modern VAT/GST audits

Technology and data analysis tools are transforming how and where VAT/GST audits are being performed. With the added pressure of tax officials carrying out more inspections, multinationals are challenged to keep pace with stricter reporting requirements, identify systemic weaknesses and design more efficient business processes.

Before defining your VAT/GST strategy, consider the following:

VAT/GST audits are increasing

One reason is due to governments needing funds. Another is the power of technology — investigations that would have taken months or years in the past can now be done in days or hours, freeing up tax auditors to carry out more inspections.

Risk-based audits are common

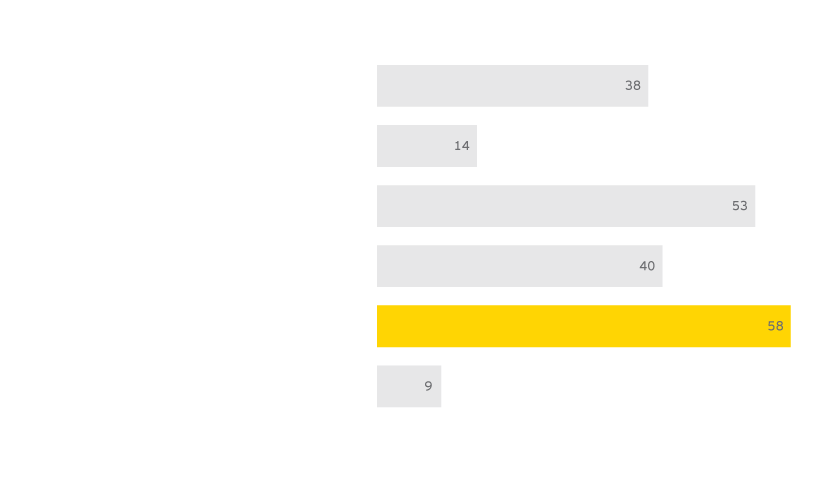

While 38 tax authorities in the countries surveyed do select taxpayers for audit at random, the majority now also apply risk-based criteria.- In 58 countries, key events, such as requesting a refund, may trigger an audit.

- In 53 countries, the taxpayers may be selected based on their industry sector.

- In 40 countries, taxpayer metrics (such as turnover compared to tax declared) play a part.

Tax administrations are collecting more VAT/GST data

Tax and customs authorities are collecting more data than ever before from VAT/ GST payers and importers about their transactions. Increasingly, they expect taxpayers to gather detailed information about customers and suppliers over and above the data they would collect for commercial purposes.Learn more at www.ey.com/indirecttaxdata.

VAT/GST data is being shared among tax administrations

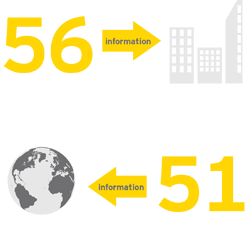

Our survey indicates that tax administrations in 56 countries share VAT/GST information with other government departments (such as customs, transfer pricing and social security), and 51 countries share VAT/GST information across borders.

Technology is transforming the tax audit landscape

The most striking trend is the rise of the e-audit. Increasingly, tax administrations are collecting indirect tax data electronically, allowing them to analyze it more quickly and more effectively.

The risk of penalties has increased

Tax administrations are imposing more penalties for non-compliance with VAT/GST obligations. Review your VAT/GST systems to ensure your business is not an easy target.VAT/GST audit outcomes

Today’s technology allows tax authorities to use diagnostic software to target taxpayers and perform audits more effectively. While some tax audits result in a “clean bill of health” for the taxpayer, many do not.

A common outcome of many VAT/GST audits is the discovery of errors in taxpayers’ reporting and accounting. If an error results in an underpayment of VAT/GST, the taxpayer is likely to face an assessment for the tax due, along with a charge for penalties and interest.

Assessments often lead to disputes. This might happen, for example, if a taxpayer does not agree with the auditor’s assessment that an error occurred, with the calculation of the taxes due, or with the penalty.

Dealing with difficult tax audits and their aftermath can be costly and time-consuming for taxpayers, and disruptive to business. Addressing common areas of weakness in VAT/GST compliance can greatly improve indirect tax performance – leading to better audit outcomes.

Deliver your data on time and in the right format

The increase in e-audits by tax administrations has gone hand in hand with the rise in the use of electronic invoicing and storage of data.

Lack of harmonization causes headaches for multinationals

Tax administrations differ in their demands for how VAT/GST data should be stored, archived and transmitted. Some require taxpayers to maintain special tax audit files (such as the SAF-T), while others request access to taxpayer’s ERP systems or use data submitted by taxpayers on a regular basis.Many use a combination of these data sources. The differences between e-audit practices and data legislation in different countries make it hard for international companies to standardize data practices. Even in the EU, VAT laws are harmonized, with every Member State having its own rules.

Adopt data policies and formats

To prepare for e-audits, you should adopt policies and practices for storing, archiving and retrieving VAT/GST data. In many countries, the information requested by the tax auditors must be available at very short notice and in the format they require.

Is SAF-T the answer?

The standard audit file for tax (SAF-T) is the closest approach to a consistent way of managing tax audits.The OECD project: The SAF-T was originally created by the OECD. It is intended to give tax authorities easy access to relevant data in an easily readable format, to allow more efficient and effective tax inspections.

A growing number of tax administrations around the world are implementing e-audits of a business’s financial records and systems. Countries are adopting tools that can interrogate these records on the basis that they must support the SAF-T methodology.

For example, Singapore is encouraging businesses to adopt the SAF-T standards. Portugal requires large companies to use SAF-T, and Brazil, notably, can require a business to hand over all its electronic financial records for scrutiny.

Adoption in the EU: SAF-T is currently used in Austria, France (on a voluntary basis), Luxembourg, Portugal and Singapore. Discussions on adopting SAF-T have taken place in Belgium, Croatia, Finland, Germany, Lithuania, Malta, Spain, the Slovak Republic, Slovenia and the UK.

Sweden and the Netherlands have their own e-audit file standards, and Germany has a mandatory electronic tax balance sheet.

The European Commission is looking to develop an EU SAF-T, along the lines of what is already in force or under development in certain Member States. It believes this would both facilitate ongoing compliance by taxpayers and allow tax administrations to carry out more effective tax audits.

A pilot project is currently under development in the specific context of the MOSS for telecommunications, broadcasting and electronic services, and further developments may be expected to follow.

XXX . V0000 Financial Services Authority

The Financial Services Authority (FSA) was a quasi-judicial body responsible for the regulation of the financial services industry in the United Kingdom between 2001 and 2013. It was founded as the Securities and Investments Board ("SIB") in 1985. Its board was appointed by the Treasury, although it operated independently of government. It was structured as a company limited by guarantee and was funded entirely by fees charged to the financial services industry.[1][2]

Due to perceived regulatory failure of the banks during the financial crisis of 2007–2008, the UK government decided to restructure financial regulation and abolish the FSA.[3] On 19 December 2012, the Financial Services Act 2012 received royal assent, abolishing the FSA with effect from 1 April 2013. Its responsibilities were then split between two new agencies: the Financial Conduct Authority and the Prudential Regulation Authority of the Bank of England.

Until its abolition, Lord Turner of Ecchinswell was the FSA's chairman[4] and Hector Sants was CEO until the end of June 2012, having announced his resignation on 16 March 2012.[5]

Its main office was in Canary Wharf, London, with another office in Edinburgh. When acting as the competent authority for listing of shares on a stock exchange, it was referred to as the UK Listing Authority (UKLA),[6] and maintained the Official List.

SIB

The Securities and Investments Board Ltd ("SIB") was incorporated on 7 June 1985 at the instigation of the UK Chancellor of the Exchequer, who was the sole member of the company and who delegated certain statutory regulatory powers to it under the then Financial Services Act 1986. It had the legal form of a company limited by guarantee (number 01920623). After a series of scandals in the 1990s, culminating in the collapse of Barings Bank, there was a desire to bring to an end the self-regulation of the financial services industry and to consolidate regulatory responsibilities which had been split amongst multiple regulators.The SIB revoked the recognition of The Financial Intermediaries, Managers and Brokers Regulatory Association (FIMBRA) as a Self-Regulatory Organisation (SRO) in the United Kingdom in June 1994, subject to a transitional wind-down period to provide for continuity of regulation, whilst members moved to the Personal Investment Authority (PIA), which in turn was subsumed.

FSA

The name of the Securities and Investments Board was changed to the Financial Services Authority on 28 October 1997 and it started to exercise statutory powers given to it by the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 that replaced the earlier legislation and came into force on 1 December 2001. At that time the FSA also took over the role of the Securities and Futures Authority (SFA) which had been a self-regulatory organisation responsible for supervising the trading in shares and futures in the UK.[7]In addition to regulating banks, insurance companies and financial advisers, the FSA regulated mortgage business from 31 October 2004 and general insurance intermediaries (excluding travel insurance) from 14 January 2005.

Abolition

On 16 June 2010, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, George Osborne, announced plans to abolish the FSA and separate its responsibilities between a number of new agencies and the Bank of England. The Financial Conduct Authority would be responsible for policing the financial activities of the City and the banking system.[8] A new Prudential Regulation Authority would carry out the prudential regulation of financial firms, including banks, investment banks, building societies and insurance companies.[8]On 19 December 2012 the Financial Services Act 2012 received royal assent and came into force on 1 April 2013.[9] The act created a new regulatory framework for financial services and abolished the FSA.[9] Specifically, the Act gave the Bank of England responsibility for financial stability, bringing together macro and micro prudential regulation, and created a new regulatory structure consisting of the Bank of England's Financial Policy Committee, the Prudential Regulation Authority and the Financial Conduct Authority.[9]

The Financial Capability division of the FSA broke away from the organisation in 2010, and became known as the Money Advice Service.

Activities

Scope

Companies involved in any of the following activities had to be regulated by the FSA.- Accepting deposits

- Issuing e-money

- Effecting or carrying out contracts of insurance as principal

- Dealing in investments (as principal or agent)

- Arranging deals in investments, regulated mortgage contracts,[10] home reversion plans, or home purchase plans

- Managing investments

- Assisting in the administration and performance of a contract of insurance[11]

- Safeguarding and administering investments

- Sending dematerialised instructions

- Establishing etc. collective investment schemes, personal pension schemes, or stakeholder pension schemes

- Advising on investments, regulated mortgage contracts, regulated home reversion plans, or regulated home purchase plans

- Lloyd's insurance market activities

- Entering into and administering a funeral plan, regulated mortgage contract, home reversion plan or a home purchase plan

- Agreeing to do most of the above activities

Statutory objectives

The Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 imposed four statutory objectives upon the FSA:- market confidence: maintaining confidence in the financial system;

- financial stability: contributing to the protection and enhancement of stability of the UK financial system;

- consumer protection: securing the appropriate degree of protection for consumers; and

- reduction of financial crime: reducing the extent to which it is possible for a business carried on by a regulated person to be used for a purpose connected with financial crime.

Regulatory principles

The statutory objectives were supported by a set of principles of good regulation which the FSA had to have regard to when discharging its functions. These were:- efficiency and economy: the need to use its resources in the most efficient and economic way.

- role of management: a firm’s senior management is responsible for its activities and for ensuring that its business complies with regulatory requirements. This principle is designed to guard against unnecessary intrusion by the FSA into firms’ business and requires it to hold senior management responsible for risk management and controls within firms. Accordingly, firms must take reasonable care to make it clear who has what responsibility and to ensure that the affairs of the firm can be adequately monitored and controlled.

- proportionality: The restrictions the FSA imposes on the industry must be proportionate to the benefits that are expected to result from those restrictions. In making judgements in this area, the FSA takes into account the costs to firms and consumers. One of the main techniques they use is cost benefit analysis of proposed regulatory requirements. This approach is shown, in particular, in the different regulatory requirements applied to wholesale and retail markets.

- innovation: The desirability of facilitating innovation in connection with regulated activities. For example, allowing scope for different means of compliance so as not to unduly restrict market participants from launching new financial products and services.

- international character: Including the desirability of maintaining the competitive position of the UK. The FSA takes into account the international aspects of much financial business and the competitive position of the UK. This involves co-operating with overseas regulators, both to agree international standards and to monitor global firms and markets effectively.

- competition: The need to minimise the adverse effects on competition that may arise from the FSA's activities and the desirability of facilitating competition between the firms it regulates. This covers avoiding unnecessary regulatory barriers to entry or business expansion. Competition and innovation considerations play a key role in the FSA's cost-benefit analysis work. Under the Financial Services and Markets Act, the Treasury, the Office of Fair Trading and the Competition Commission all have a role to play in reviewing the impact of the FSA's rules and practices on competition.

Retail consumers

The FSA had a priority of making retail markets for financial products and services work more effectively, and so help retail consumers to get a fair deal. Over several years, the FSA developed work to raise levels of confidence and capability among consumers. From 2004, this work was described as a national strategy[14] on building financial capability in the UK. This programme was comparable to financial education and literacy strategies in other OECD countries, including the United States.In June 2006, the FSA created its Retail Distribution Review (RDR) programme which they maintained would enhance consumer confidence in the retail investment market. The RDR came into force on 31 December 2012.[15]

The RDR is expected to have a significant impact on the way in which financial services are delivered to retail investors in the UK.[16] The primary delivery mechanism of financial services to retail customers is via approximately 30,000 financial intermediaries (FIs) who are authorised and regulated by the FSA. They are expected to bear the brunt of the force of the RDR. The key elements of RDR are:

- Independent advice is truly independent and reflects investors’ needs.

- People can clearly identify and understand the service they are being offered.

- Commission-bias is removed from the system and recommendations made by advisers are not influenced by product providers.

- Investors know up-front how much advice is going to cost and how they will pay for it.

- All investment advisers will be qualified to a new, higher level, regarded as equivalent to the first year of a degree[17]

- Consolidators buying up small firms of FIs as a result of the higher qualifications threshold and downward pressures on profitability resulting from RDR – E&Y estimate that the number of Registered Individuals will fall from 30,000 to 20,000 within the next 5 years.[20]

- IFAs are embracing the concept of wrap account – incumbent fund supermarkets and Life Assurance Companies are in response launching their own Wrap Platforms.[21]

- IFAs are rapidly moving from the traditional investment solution for clients: recommending a portfolio of largely equity-oriented collective investment schemes (Unit trusts and OEICs) and being paid initial and annual renewal commission by the fund provider to an outsourcing model: recommending that clients appoint a discretionary fund manager to manage the client's portfolio(s) and charging the client an annual oversight fee. A recent survey found that 89% of IFAs are considering outsourcing to discretionary managers as a result of RDR.[22]

- Several new entrants are making major in-roads into this market[23][24] at the expense of the incumbent retail-oriented funds groups such as Schroders, Gartmore, Fidelity Investments etc.[25] The larger discretionary fund managers are finding it difficult to adapt their business models to cope with these changes, given that the small average portfolio size is better suited[26] to multi-manager (portfolio of funds) solutions,[27] via wrap platforms, when these fund managers tend to prefer to retain custody and investing in direct equities.[28]

2009 regulations

The Payment Services Regulations 2009 came into force on 1 November 2009[29] and shifted the onus onto the banks to prove negligence by the holder of debit and credit cards in cases of disputed payments.[30] The FSA said "It is for the bank, building society or credit card company to show that the transaction was made by you, and there was no breakdown in procedures or technical difficulty" before refusing liability.On the same date the Banking Conduct Regime commenced.[31] It applies to the regulated activity of accepting deposits, and replaces the non-lending aspects of the Banking Code and Business Banking Code (industry-owned codes that were monitored by the Banking Code Standards Board).

Organisation

Management and accountability

The FSA was not accountable to Treasury Ministers or to Parliament, as confirmed by Hector Sants at a Treasury Select Committee meeting on 9 March 2011. Sants told TSC Chair, Andrew Tyrie, that Parliament needed to legislate to remove the FSA's non-accountable status. This was further confirmed by Mark Garnier MP who, when commenting on the FSA's negative reaction to a Treasury Select Committee (TSC) report on the RDR, stated that if the FSA chose to ignore the TSC there was nothing they could do about it.It was operationally independent of Government and was funded entirely by the firms it regulated through fines, fees and compulsory levies. Its Board consisted of a chairman, a chief executive officer, a chief operating officer, two Managing Directors, and 9 non-executive directors (including a lead non-executive member, the Deputy chairman) selected by, and subject to removal by, HM Treasury. Among these, the Deputy Governor for Financial Stability of the Bank of England was an 'ex officio' Board member.

This Board decided on overall policy with day-to-day decisions and management of the staff being the responsibility of the Executive. This was divided into three sections each headed by a Managing director and having responsibility for one of the following sectors: retail markets, wholesale and institutional markets, and regulatory services.

Its regulatory decisions could be appealed to the Financial Services and Markets Tribunal.

HM Treasury decided upon the scope of activities that should be regulated, but it was for the FSA to decide what shape the regulatory regime should take in relation to any particular activities.

The FSA was also provided with advice on the interests and concerns of consumers by the Financial Services Consumer Panel.[32] This panel described itself as "An Independent Voice for Consumers of Financial Services". Members of the panel were appointed and could be dismissed by the FSA and emails to them were directed to FSA staff. The Financial Services Consumer Panel did not address individual consumer complaints.

Board

Lord Turner, Chairman of the Financial Services Authority.

- Adair Turner – Executive chairman

- Deputy chairman – vacant, following resignation of Sir James Crosby

- Andrew Bailey – managing director, Prudential Business Unit

- Martin Wheatley – managing director, Conduct Business Unit

- Lesley Titcomb – Acting chief operating officer, the FSA

- Carolyn Fairbairn – Non-executive FSA Board member, Director of Strategy and Development at ITV plc

- Peter Fisher – Non-executive FSA Board member, managing director of BlackRock

- Brian Flanagan – Non-executive FSA Board member, formerly a Vice-President of Mars Inc

- Karin Forseke – Non-executive FSA Board, formerly CEO of Carnegie Investment Bank AB

- Sir John Gieve – Non-executive FSA Board member, Deputy Governor, Financial Stability of the Bank of England

- Professor David Miles – Non-executive FSA Board member, managing director and Chief UK Economist at Morgan Stanley

- Michael Slack – Non-executive FSA Board, Director of the British Insurance Brokers' Association

- Hugh Stevenson – Non-executive FSA Board member, Chairman of the FSA Pension Plan Trustee Ltd

- Mick McAteer – Non-executive FSA Board member, director, Financial Inclusion Centre.

Criticisms

)

|

The FSA in an internal report into the handling of the collapse in confidence of customers of the Northern Rock Plc described themselves as inadequate.[36] It was reported that to prevent such a situation occurring again, the FSA was considering allowing a bank to delay revealing to the public when it gets into financial difficulties.[37]

The FSA was criticised in the final report of the European Parliament's inquiry into the crisis of the Equitable Life Assurance Society.[38] It is widely reported that the long-awaited Parliamentary Ombudsman's investigation into the government's handling of Equitable Life is equally scathing of the FSA's handling of this case[39]

The FSA ignored warning signals from Northern Rock building society and continued to allow the bank to operate without a risk mitigation programme for months before the bank's collapse.[40]

The FSA was criticised by some within the IFA community for increasing fees charged to firms and for the perceived retroactive application of current standards to historic business practices.[citation needed]

The perceived lack of action by the FSA in many cases, and allegations of regulatory capture led to it being nicknamed the Fundamentally Supine Authority by Private Eye magazine.

The FSA was not legally able to circumvent statute yet hid behind secret legal opinion regarding its summary removal of practitioners' legal rights in respect of their ability to use a longstop defence against stale claims.

FSA regulation was also often regarded as reactive rather than proactive.[citation needed] In 2004–05 the FSA was actively involved in crackdowns against financial advice firms who were involved in the selling of split-cap investment trusts and precipice bonds, with some success in restoring public confidence.[citation needed]. However, despite heavily criticising split-cap investment trusts, in 2007 it suddenly abandoned its investigation.[41] Where it was rather poorer in its remit is in actively identifying and investigating possible future issues of concern, and addressing them accordingly.[citation needed]

There were also some questions raised about the competence of FSA staff.[42]

The composition of the FSA board appeared to consist mainly of representatives of the financial services industry and career civil servants. There were no representatives of consumer groups. As the FSA was created as a result of criticism of the self-regulating nature of the financial services industry, having an independent authority staffed mainly by members of the same industry could be perceived as not providing any further advantage to consumers.

Although one of the prime responsibilities of the FSA was to protect consumers, the FSA was active in trying to ensure companies' anonymity when they were involved in misselling activity, preferring to side with the companies that have been found guilty rather than consumers.[43][44]

This was most obviously seen in the case known as the LAUTRO 19, where the FSA identified 19 insurers which had breached their contractual warranties by using incorrect charges to calculate the premiums for mortgage endowment policies. This miscalculation led to massive consumer detriment as well as vast and unquantifiable costs for the advisers who unwittingly sold these products. The FSA steadfastly refused to publicly name the miscreant companies and spent £100,000s on legal fees to baulk the efforts of the Information Commissioner who had concluded that naming the companies would be in the public interest.

It was announced in November 2008, that despite self-acknowledged failures by the FSA in effectively regulating the financial services industry, FSA staff would receive bonuses.[45] On 31 May 2008, The Times confirmed that FSA staff had received £20m in bonuses for 2008/09, a 40% increase on the previous year.[46]

On 11 February 2009, FSA deputy chairman, Sir James Crosby resigned after it was revealed that he had fired a whistleblower, Paul Moore, who had warned of dangerous lending practices at HBOS when he had been in charge of risk regulation.[47]

Lord Adair Turner, the then FSA chairman, defended the actions of the regulator on the BBC's Andrew Marr show on 13 February 2009. His comments were that other regulatory bodies throughout the world, which had a variety of different structures and which are perceived either as heavy touch or light touch also failed to predict the economic collapse. In line with the other regulators, the FSA had failed intellectually by focusing too much on processes and procedures rather than looking at the bigger economic picture. In response as to why Sir James Crosby had been appointed deputy chairman when his bank HBOS had been highlighted by the FSA as using risky lending practises, Lord Turner said that they had files on almost every financial institution indicating a degree of risk.[48]

Turner faced further criticism from the Treasury Select Committee on 25 February 2009, especially over failures to spot or act on reckless lending by banks before the crisis of 2008 occurred. He attributed much of the blame on the politicians at the time for pressuring the FSA into "light touch" regulation.[49]

On 17 April 2009, a whistleblower (former FSA employee) alleged that the FSA had turned a blind eye to the explosion in purchases of whole sale loans taken on by various UK building societies from 2005 onwards. The FSA denied the claims – "This is not whistleblowing, it is green ink" a spokesman said. "The allegations are a farrago of lies, distortions and half truths made by an obviously disgruntled former employee who clearly has an axe to grind. It does not paint a realistic picture of our supervision of building societies."

On 18 August 2012, the Treasury Select Committee criticised the FSA for its poor enforcement of the LIBOR rate setting rules.[51]

More principles-based regulation

There were suggestions that the FSA stifled the UK financial services industry through over-regulation, following a leaked letter from Prime Minister Tony Blair during 2005. This incident led Callum McCarthy, then Chief Executive of the FSA, to formally write to the Prime Minister asking him to either explain his opinions or retract them.[52]The Prime Minister's criticisms were viewed as particularly surprising since the FSA's brand of light-touch financial regulation was typically popular with banks and financial institutions in comparison with the more prescriptive rules-based regulation employed by the US Securities and Exchange Commission and by other European regulators;[53] by contrast, most critiques of the FSA accused it of instigating a regulatory "race to the bottom" aimed at attracting foreign companies at the expense of consumer protection.[54]

The FSA countered that its move away from rules-based regulation towards more principles-based regulation, far from weakening its consumer protection goals, could in fact strengthen them: "Our Principles are rules. We can take enforcement action on the basis of them; we have already done so; and we intend increasingly to do so where it is appropriate to do so."[55] As an example, the enforcement action taken in late 2006 against firms mis-selling payment protection insurance was based on their violation of principle six of the FSA's Principles for Business, rather than requiring the use of the sort of complex technical regulations that many in financial services find burdensome.[56]

Enforcement cases

The FSA was criticised for its supposedly weak enforcement program.[ For example, while FSMA prohibits insider trading, the FSA only successfully prosecuted two insider dealing cases, both involving defendants who did not contest the charges.[60] Likewise, since 2001, the FSA only sought insider trading fines eight times against individuals and companies it regulated,[61] despite the FSA's own studies indicating that unexplained price movements occur prior to around 25 percent of all UK corporate merger announcements.[62]After the HBOS insider trading scandal, the FSA informed MPs on 6 May 2008 that they planned to crack down on inside trading more effectively and that the results of their efforts would be seen in 2008/09[63] On 22 June, the Daily Telegraph reported that the FSA had wrapped up their case into HBOS insider trading and no action would be taken.[64] On 26 June, the HBOS chairman said that "There is a strong case for believing that the UK is exceptionally bad at dealing with white-collar crime".[65]

On 29 July 2008, however, it was announced that the Police, acting on information supplied by the FSA, had arrested workers at UBS and JP Morgan Cazenove for alleged insider dealing and that this was the third case within a week.[66] A year after the subprime mortgage crisis had made global headlines, the FSA levied a record £900,000 on an IFA for selling subprime mortgages.[67]

Actions relating to the 2007—2009 credit crisis

The FSA was held by some observers to be weak and inactive in allowing irresponsible banking to precipitate the credit crunch which commenced in 2007, and which has involved the shrinking of the UK housing market, increasing unemployment (especially in the financial and building sectors), the public acquisition of Northern Rock in mid-February 2008, and the takeover of HBOS by Lloyds TSB. On 18 September 2008, the FSA announced a ban on short selling to reduce volatility in difficult markets lasting until 16 January 2009.[68][69]Certainly, the FSA's implementation of capital requirements for banks was lax relative to some other countries. For example, it was reported[70] that Australia's Commonwealth Bank is measured as having 7.6% Tier 1 capital under the rules of the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority, but this would be measured as 10.1% if the bank was under the jurisdiction of the FSA.

In March 2009, Lord Turner published a regulatory review of the global financial crisis.[71] The review broadly acknowledges that 'light touch' regulation had failed and that the FSA should concentrate on macroeconomic regulation as well as scrutinising individual companies. The review also proposed cross-border regulation of banks. There were no further promises to improve consumer protection or to directly intervene against financial institutions who treat their customers badly. The review was reportedly met with widespread relief in the city of London where firms had feared a 'revolution' in the way that they would be regulated.[72]

Visual identity

The graphic identity at the time of abolition, including the logotype which is intended to symbolise the 'world of finance', was created in 1997 by the British design consultancy Lloyd Northover, founded by John Lloyd and Jim Northover.XXX . V00000 International funds transfer instructions (IFTIs)

Contents

- What are the IFTI reporting obligations?

- International electronic funds transfer instruction (IFTI-E)

- IFTI under a designated remittance arrangement (IFTI-DRA)

- Is a registered affiliate of a remittance network provider required to report IFTIs?

- Scenarios of common international funds transfers conducted by casino licence holders

- When must a reporting entity provide further information about an IFTI?

- What are the penalties for failing to report an IFTI?

- Are there any exemptions to the IFTI reporting obligations?

What are the IFTI reporting obligations?

The 'sender' of an IFTI transmitted out of Australia, or the 'recipient' of an IFTI transmitted into Australia, must report the instruction to AUSTRAC within 10 business days after the day the instruction was sent or received.There are two categories of IFTIs:

- international electronic funds transfer instructions (IFTI-E)

- instructions given under a designated remittance arrangement (IFTI-DRA)

International electronic funds transfer instruction (IFTI-E)

What is an electronic funds transfer instruction (EFTI)?

Under the AML/CTF Act, an electronic funds transfer instruction (EFTI) is an electronic instruction sent between an 'ordering institution' and a 'beneficiary institution'.An ordering institution or beneficiary institution can be:

- an ADI

- a bank, building society or a credit union

- persons specified in the AML/CTF Rules.

An electronic funds transfer instruction can be either a domestic electronic funds transfer instruction or an international electronic funds transfer instruction (IFTI-E). There are different reporting requirements for domestic and international EFTIs.

What is an international electronic funds transfer instruction?

An IFTI-E occurs when:- the ordering institution accepts the instruction at or through a permanent establishment in Australia and the transferred money is made available to the payee at or through a permanent establishment of the beneficiary institution in a foreign country, (an outgoing IFTI-E)

- the ordering institution accepts the instructions at or through a permanent establishment in a foreign country and the money is transferred to a permanent establishment of the receiving institution in Australia (an incoming IFTI-E).

Who are the key parties involved in an IFTI-E?

The key parties of an IFTI-E are:- the 'payer', who requests the 'ordering institution' (institution that accepts the instruction from the payer) to transmit the instruction

- the 'sender' (either the ordering institution or another institution), who transmits the instruction to the 'beneficiary institution' via any 'interposed institutions' (that is, institutions that take part in the instruction between the sender and the beneficiary institution)

- the beneficiary institution, which ultimately makes the funds available to the 'payee' (the person who receives the transferred funds) (figure 1).

Figure 1: Parties involved in an international electronic funds transfer instruction

What information must be reported in an IFTI-E?

Chapter 16 of the AML/CTF Rules sets out the reportable details that must be included in IFTI-E reports for each party involved in the funds transfer.IFTI under a designated remittance arrangement (IFTI-DRA)

What is an IFTI-DRA?

An IFTI-DRA involves:- an instruction accepted at or through a permanent establishment of a 'non-financier' in Australia, where the person who receives the instruction is to make, or arranges to make, money or property available to the ultimate transferee at or through a permanent establishment of a person in a foreign country; or,

- an instruction accepted at or through a permanent establishment of a person in a foreign country where a 'non‑financier' is to make, or arranges to make, money or property available to the ultimate transferee through a permanent establishment of the non-financier in Australia.

Example 1

Customer A wants to send AUD5,000 to his brother (Mr A) who lives in Vietnam. Customer A contacts ABC Remittance Ltd, a registered remittance provider and instructs them to send AUD5,000 to Mr A in Vietnam.ABC Remittance Ltd arranges to make AUD5,000 available to Mr A by sending an SMS text message to its agent in Vietnam. The agent arranges to have AUD5,000 delivered to Mr A the next business day.

ABC Remittance Ltd and the agent in Vietnam arrange to reconcile funds between them using a variety of methods. One method is to reconcile through a third party, which may occur at a later date.

ABC Remittance Ltd must submit an IFTI-DRA report to AUSTRAC, detailing the international funds transfer instruction within 10 business days of receiving the instruction.

Example 2

Customer B wants to send AUD2,000 to her family in India. Customer B contacts ABC Remittance Ltd, a registered remittance provider and instructs them to send AUD2,000 to Mr B in India. Customer B provides ABC Remittance Ltd with a cheque for AUD2,000.ABC Remittance Ltd contacts its agent in India via email. ABC Remittance Ltd deposits the funds in its bank account with DEF Bank in Australia and transfers the AUD2,000 from its bank account to the agent's bank account with DEF Bank in India. The agent arranges to have the AUD2,000 delivered to Mr B in India.

ABC Remittance Ltd must submit an IFTI-DRA report to AUSTRAC, detailing the international funds transfer instruction within 10 business days of receiving the instruction.

What information must be reported in an IFTI-DRA?

Chapter 17 of the AML/CTF Rules specifies the reportable details for an IFTI-DRA.Is a registered affiliate of a remittance network provider required to report IFTIs?

No. The remittance network provider is responsible for reporting IFTIs on behalf of its affiliates where the reportable transaction uses the network provided by the remittance network provider.Scenarios of common international funds transfers conducted by casino licence holders

Below are six examples of the common types of international funds transfers conducted by licensed casinos that are required to be reported to AUSTRAC. While the examples cover common scenarios faced by casinos, they are not exhaustive.Some of these scenarios would also require the financial institution facilitating the funds transfer to report IFTIs in relation to the funds transfer; however, this obligation does not affect the casino’s own obligation to submit an IFTI-DRA report. IFTI-DRA reports submitted by casinos have significant intelligence value as casinos are required to report information about the beneficiary of the transferred funds – this information would not necessarily be known or reported by the financial institution(s) facilitating the transfer.

Scenario 1: Incoming IFTI-DRA

An overseas customer (Customer A) negotiates a ‘casino player’ agreement with the Australian casino. The casino player agreement is finalised at the casino’s international office in a foreign country. The casino player agreement contains the date of the visit and the amount to be deposited in the casino’s bank account by customer A prior to that visit.

As agreed in the casino player agreement, customer A instructs their local bank in a foreign country to transfer AUD150,000 to the Australian casino’s bank account, held with a bank in Australia.

Once the funds are received into the casino’s bank account in Australia, the casino makes the funds available to customer A by crediting his/her casino gaming account.

Instructions into Australia must contain information in a report regarding the transferor entity (given that Customer A is an individual) and ultimate transferee entity as detailed in Chapter 17 of the AML/CTF Rules. Further details are also required to be reported as set out in Chapter 17 of the AML/CTF Rules.

As agreed in the casino player agreement, customer A instructs their local bank in a foreign country to transfer AUD150,000 to the Australian casino’s bank account, held with a bank in Australia.

Once the funds are received into the casino’s bank account in Australia, the casino makes the funds available to customer A by crediting his/her casino gaming account.

Reporting obligation

The Australian casino is the recipient of the IFTI-DRA transmitted into Australia and is required to report an incoming IFTI-DRA as it is within the meaning of item 4 in the table in section 46 of the AML/CTF Act.Instructions into Australia must contain information in a report regarding the transferor entity (given that Customer A is an individual) and ultimate transferee entity as detailed in Chapter 17 of the AML/CTF Rules. Further details are also required to be reported as set out in Chapter 17 of the AML/CTF Rules.

Scenario 2: Outgoing IFTI-DRA

Customer B instructs the Australian casino to transfer AUD150,000 from their casino gaming account to their personal bank account with an overseas bank, or to a third-party bank account outside Australia (for example, another casino’s bank account or an account held by another person).

The Australian casino instructs the Australian bank to transfer the equivalent of AUD150,000 to the customer B’s personal bank account with an overseas bank (or any other overseas bank account specified by the customer).

Instructions transmitted outside of Australia must contain details in a report about the transferor entity (includes at a minimum their full name, date of birth, residential address), transmitter and ultimate transferee entity. Further details are also required to be reported as set out in Chapter 17 of the AML/CTF Rules.

The Australian casino instructs the Australian bank to transfer the equivalent of AUD150,000 to the customer B’s personal bank account with an overseas bank (or any other overseas bank account specified by the customer).

Reporting obligation

The Australian casino is the sender of the IFTI-DRA transmitted out of Australia and is required to report an outgoing IFTI-DRA as it is within the meaning of item 3 in the table in section 46 of the AML/CTF Act.Instructions transmitted outside of Australia must contain details in a report about the transferor entity (includes at a minimum their full name, date of birth, residential address), transmitter and ultimate transferee entity. Further details are also required to be reported as set out in Chapter 17 of the AML/CTF Rules.

Scenario 3: Outgoing IFTI-DRA – inter-company transfer

The Australian casino has a related casino in a foreign country (that is, the two casinos are owned or operated by the same parent company).Customer C instructs the Australian casino to transfer AUD150,000 held in their casino gaming account to his/her casino gaming account held with the related casino in a foreign country.

There is no physical transfer of the funds (that is, no bank transfer is involved) and there is an inter-company journal entry to recognise the position so that the funds can be made available to customer C when they arrive at the related casino in a foreign country.

The related casino in a foreign country makes the equivalent of AUD150,000 available to customer C through their gaming account, on the basis of the funds available in customer C’s gaming account with the Australian casino.

Reporting obligation

The Australian casino is the sender of the IFTI-DRA transmitted out of Australia and is required to report an outgoing IFTI-DRA as it is within the meaning of item 3 in the table in section 46 of the AML/CTF Act.Instructions transmitted out of Australia must contain details in a report about the transferor entity and ultimate transferee entity (in this case Customer C is both the transferor entity and ultimate transferee entity) and mandatory information as detailed in Chapter 17 of the AML/CTF Rules.

Scenario 4: Incoming IFTI-DRA – inter-company transfer

The Australian casino has a related casino in a foreign country (that is, the two casinos are owned or operated by the same parent company).Customer D instructs a related casino in a foreign country to transfer AUD150,000 held in their casino gaming account to his/her casino gaming account held by the related casino in Australia.

There is no physical transfer of the funds (that is, no bank transfer is involved) and there is an inter-company journal entry to recognise the position so that the funds can be made available to the customer when they arrive at the related casino in Australia.

The related casino in Australia makes the equivalent of AUD150,000 available to customer D through their gaming account, on the basis of the funds available in the customer D’s gaming account with the related casino in a foreign country.

Reporting obligation

The Australian casino is the recipient of the IFTI-DRA transmitted into Australia and is required to report an incoming IFTI-DRA as it is within the meaning of item 4 in the table in section 46 of the AML/CTF Act.The IFTI-DRA must contain information in a report regarding the transferor entity and ultimate transferee entity as detailed in Chapter 17 of the AML/CTF Rules. Further details are also required to be reported as set out in Chapter 17 of the AML/CTF Rules.

Scenario 5: Incoming IFTI-DRA – international transfer of funds originating from a cheque

Customer E is based outside of Australia and holds a casino gaming account with an Australian casino. Customer E provides a cheque for AUD150,000 to the staff at the Australian casino’s international office (in a foreign country) on the basis that the funds equivalent to the amount of the cheque will be made available by the Australian casino in customer E’s gaming account.The staff at the international office deposit the cheque into the Australian casino’s bank account held in an overseas bank. The proceeds of the cheque remain in the Australian casino’s bank account held at an overseas bank.

The Australian casino is notified of the transaction by staff at the international office. The Australian casino prepares the funds for the customer for when they arrive in Australia in recognition of the funds held in the Australian casino’s account with the overseas bank.

Customer E arrives at the Australian casino and AUD150,000 is made available in the customer’s casino gaming account.

Reporting obligation

The Australian casino is the recipient of the IFTI-DRA transmitted into Australia and is required to report an incoming IFTI-DRA as it is within the meaning of item 4 in the table in section 46 of the AML/CTF Act.The IFTI-DRA must contain information in a report regarding the transferor entity and ultimate transferee entity as detailed in Chapter 17 of the AML/CTF Rules. Further details are also required to be reported as set out in Chapter 17 of the AML/CTF Rules.

Scenario 6: Outgoing IFTI-DRA – international transfer of funds through a bank account held by a subsidiary company

The Australian casino has a 100 per cent owned and controlled subsidiary company located in Australia which operates a bank account with an Australian bank. The state casino regulator has approved and authorised the bank account on the basis that the subsidiary company is a 100 per cent owned and controlled entity of the Australian casino (where required by the state casino regulator).

Customer F instructs the Australian casino to transfer AUD150,000 (from the bank account held by the subsidiary company) into their personal overseas bank account.

Reporting obligation

The Australian casino is the sender of the IFTI-DRA transmitted out of Australia and is required to report an outgoing IFTI-DRA as it is within the meaning of item 3 in the table in section 46 of the AML/CTF Act.

Instructions transmitted outside of Australia must contain details in a report about the transferor entity (includes at a minimum their full name, date of birth, residential address), transmitter and ultimate transferee entity. Further details are also required to be reported as set out in Chapter 17 of the AML/CTF Rules.

Is a registered affiliate of a remittance network provider required to report IFTIs?

No. The remittance network provider is responsible for reporting IFTIs on behalf of its affiliates where the reportable transaction uses the network provided by the remittance network provider.When must a reporting entity provide further information about an IFTI?

AUSTRAC (and officials from certain AUSTRAC partner agencies in certain circumstances) can issue a written notice to a reporting entity (or any other person), requiring it to produce further information about an IFTI submitted to AUSTRAC. This further information may be information the entity has about the customer or a particular transaction that can assist in an investigation (for example, account information, customer details or a statement of transactions).A reporting entity failing to comply with such a notice may incur a civil penalty.

What are the penalties for failing to report an IFTI?

If an IFTI report is submitted after the reporting period of 10 business days or not submitted at all, AUSTRAC can apply to the Federal Court of Australia for a civil penalty order of up to 100,000 penalty units for a body corporate, and up to 20,000 penalty units for a person other than a body corporate.Are there any exemptions to the IFTI reporting obligations?

The AML/CTF Rules can specify exemptions from the IFTI reporting obligations. To date, no exemptions have been made from the IFTI reporting obligation.XXX . V0000 The Disadvantages of Computer-Assisted Audit Techniques

With the technological age and the advancement of computers in the business profession, the advancement of auditing techniques to evaluate programs and transactions have also gone to an electronic format. Computer-assisted audit techniques, or CAATs, allow auditors to review data from computer applications. Yet many auditors refrain from using CAATs based on compatibility with the company's computer systems.

Audit Software

When an auditor uses CAATs for auditing software, this involves reading the client's data files. By using this procedure, the auditor locates the information necessary to perform different auditing tasks. Yet the auditor runs into disadvantages by needing the necessary training skills to run the complicated auditing programs. This technique raises costs to auditors who must ensure programs are adaptable from computer to computer.

Database Analyzers

The auditor uses database analyzers to examine software rights the business has to use different applications. The auditor reviews application access for users to work with the information in the database. Unfortunately, CAATs have limited applicability to auditing these different database management systems. The auditor also must have the necessary skills to set up and understand the auditing results.

Embedded Program Code

CAATs provide the auditor to set up his own program to evaluate transactions moving through the computer system for processing. Several disadvantages in this setup include that the auditor experiences extra overhead in using extra programs to install into the company's software. The auditor must note when an unusual transaction happens, which may be difficult if not understanding the normal types of business transactions. The auditor also runs the risk of security issues if unauthorized users access the software program.

Online Program Testing

To perform online testing, the auditor creates real and fake data that manipulate the specific program. This allows the auditor to see whether the screen edit test is functioning properly. The auditor doesn't see an advantage of using CAATs during this testing, because real data may corrupt the results. Another disadvantage is that the auditor is permitted to use only one type of online program at a time to satisfy only one type of specific objective, cutting into his auditing time.

Advantages of Paperless Audits

The increased use of electronic systems for accounting and financial management in companies has decreased the use of physical documents in many companies. The reliance on digital record management systems and financial accounting programs has allowed some auditing firms to offer paperless auditing to companies that primarily run a paperless office. Models for a paperless audit have been established through government regulations, auditing companies’ preferred methods and accounting organization proposals.

Accessibility

Companies that opt for a paperless audit can provide increased accessibility to financial documents and statements for auditing personnel. Increased accessibility can decrease the amount of time required by accounting and financial staff to provide documents to auditors. Depending on security requirements, accessibility may allow auditors to conduct their review from outside the business facility.

Tracking Ability

Most paperless audit systems offer reporting and tracking abilities throughout the auditing process. Managers from the company being audited as well as the auditing firm's management can easily track and monitor each step in the review process. This increased tracking may help streamline resource requirements and helps manage the auditing timeline. Tracking and time management can be essential, especially for public companies with SEC-mandated reporting deadlines.

Less Waste

Reducing the need for duplicate copies of financial documents, storage facilities and office supplies can reduce the amount of waste both companies generate. Paperless audits use less paper, ink toner, electricity and office supplies than a traditional paper-bound audit. The reduction in paper and associated supplies can offer cost savings and an ecological benefit. This green focus may be important for companies that want to promote their company as being environmentally-friendly.

Faster Review

A paperless audit may take less time than a traditional paper-trail audit process. Financial documents can be easily loaded for review and analysis with greater accuracy. Electronic processing of audit tasks minimizes human errors and the need to manually enter information into an auditing system. When an audit item is flagged for additional review, auditors can easily send the information to the financial lead for review and additional information. Electronic reviews may take less time than in-person physical meetings with paper forms. Less manual work and easier reviews can decrease the total auditing timeline.

Increased Security

Physical documents are more difficult to secure than electronic documents. Electronic data and documents can be secured through passwords and other digital security methods. An electronic tracking system can also notate who has reviewed each data element for security review purposes. Physical documents can be copied, lost, or placed in an unsecure location. A paperless audit increases the security of a company’s financial system.

XXX . V000000 Beyond Traditional Audit Techniques

An audit team uses innovative methods to look at how a company identifies and manages risk.

To identify risk areas and continuously monitor the company’s risk profile, we had to transform the internal audit department from its traditional role—performing checklist activities—to one that focused on corporate and business unit goals, strategies and risk management processes. To achieve this restructuring, we asked ourselves these fundamental questions:

DEFINE INTERNAL CONTROL

Simply testing control activities under a traditional audit system gives internal auditors a very narrow focus—a significant problem with our former process. To help create an auditing methodology based on process improvement and continual risk assessment, we adopted the Committee of Sponsoring Organizations of the Treadway Commission’s definition of internal control and incorporated it into our mission statement. The COSO definition expands internal audit’s traditional testing of control activities, such as policies and procedures and approvals and reconciliations, to include four additional components that derive from the way management runs a business: control environment, risk assessment, information and communication and risk monitoring ( see “ The COSO Framework: An Overview ”). To integrate these components into our enterprise-wide risk management program, we informed the business area managers we planned to work with them to address risks based on the COSO objectives—namely, effectiveness and efficiency of operations, reliability of financial reporting and compliance with applicable law and regulations. To apply the COSO definition of internal control to our audit methods, we asked company executives for ways to improve and revise Cal Fed’s audit methodology. We had complete support from Cal Fed’s top management and the audit committee to overhaul our function and implement the COSO objectives, which we knew would—and, in fact, did—require implementation in stages over several years.

ADOPT BEST PRACTICES

To assess how well the company deals with risks, we needed more then a list of required controls. With the COSO model as a guide, we developed and incorporated the following “best practices” into the audit function.

Monitor business activities and key performance indicators continuously. As internal auditors we must keep abreast of what’s happening in the organization’s environment. We do this by attending executive committee meetings, obtaining important management reports and identifying and meeting with key department heads throughout the year. For example, the consumer lending unit had had no significant problems for a number of years, so we did not schedule it for a current year audit. However, because we maintained contact with its managers we discovered the area had a new business plan to increase volume and add more employees. Because of these changes we then scheduled the unit for an audit.

Coordinate with other risk management functions. In evaluating quality control, security, asset review and credit administration processes, we try to leverage the work of other departments where possible by reviewing the scope of their activity and considering their results in our approach. For example, rather than just using our own samples for testing, we examine the unit’s quality control program and selectively validate the results. We also can coordinate the timing of an audit with a department’s ongoing loan review, draw on its findings to determine which policy interpretations caused underwriting exceptions and suggest process improvements.

Develop the audit plan based on risk priorities. Rather than scheduling audits according to a standard cycle of one-, two- or three-year rotations, we base frequency of audits on a business area’s risk factors, such as previous poor audit ratings or significant changes in personnel. This allows us to focus on the highest risk priorities within the company and to devote appropriate resources to new and changing areas. We also train managers to update their own risk assessment systems and methodologies—for example, by showing them how to implement steps to monitor quality control and segregation of duties.

Get involved in technology projects. As internal auditors we know we must be involved in activities such as systems development and conversions, process reengineering, new products and services, mergers and acquisitions and the analysis of new IT policies. At Cal Fed we look at controls before technology teams implement them and take steps to address IT risks rather than react to problems after they occur. For example, before management installed a new loan origination system, we identified supporting applications that would affect operational processes, business resumption plan requirements and network security issues, such as controlling user access and ensuring that supporting applications interacting with existing systems had proper controls. (For more information on this topic, see “ Risky Business ,” JofA, June02, page 65.)

We knew some of our auditors were more comfortable with traditional control activities, such as approval of journal entries, so we coached them to understand primary business objectives and related risks. Our audit managers accomplished this by regularly meeting with their teams throughout each stage in the audit, asking questions to foster each team’s understanding of business operations. For example, while conducting the electronic banking audit, the manager asked the team to explain how this business area generated revenue from debit card transactions and why the formulas used to determine its budget varied from the previous year.

Team members also participate in industry-related training to improve their knowledge of company issues. Before an audit, one of the team explains to area managers how to use the COSO framework to self-assess their internal controls and emphasizes that business and audit risks are really the same things. For example, following the COSO objectives of maintaining effective operations and adhering to compliance procedures, the manager of the electronic banking department set up a monthly certification process to ensure employees complied with policies to investigate unauthorized card use, thus improving controls.

BECOME PART OF THE PROCESS

While the close partnerships we have with the business areas and top management could lead to impaired objectivity, we follow certain guidelines to avoid this pitfall, taking care to act in an advisory capacity rather than exercise decision-making authority. Examples of how we used this approach in three of the company’s business units follow: