With respect to the importance of a currency for each country with a very fast, precise and efficient and correct transaction process, it is necessary to have an electronic currency transaction which will provide a sense of security and comfort as well as the accuracy of both time and value for the user of the currency or user. at the time when my graduate studies in business and finance in the year 1996 - 1999 seen that at that time currency transactions are still using the currency of currency means currency in the form of liquid transactions are very difficult and not easy in the transaction because the required amount and paper money for enormous amounts of money for money-making transactions that may make us impractical in the use of money and inflexible for the users of every citizen. A global currency is one that is accepted for trade throughout the world. Some of the world's currencies are accepted for most international transactions. The most popular are the U.S. dollar, the euro, and the yen. Another name for global currency is reserve currency.

Gen . Mac Tech

Electronic Transfer Account The Low-Cost Way To Receive Federal Benefits

The benefits of "electronic" banking--and Direct Deposit in particular--include convenience, immediate access to deposits and personal safety. You no longer need to make a trip to the bank or grocery store to cash your check, wait for a check to clear, or carry large amounts of cash.

To encourage Federal check recipients to consider an account at a financial institution and use Direct Deposit, the Department of the Treasury recently introduced an easy and affordable option-the Electronic Transfer Account (ETA). The new ETA is available through participating Federally insured financial institutions, including banks, savings and loans, and credit unions.

The account, which provides the full range of consumer protections, is available to any one who receives a Federal benefit, wage, salary or retirement payment. Features of an ETA include-

- a maximum cost of $3.00 per month;

- a minimum of four cash withdrawals per month.

- Your bank, savings and loan, or credit union will tell you whether you can get your money from a teller, an Automated Teller Machine (ATM) or both. If you use ATMs at certain locations - it may cost extra;

- no minimum balance, unless the law requires it;

- a monthly statement listing all deposits and withdrawals; and

- federally insured accounts.

Electronic Concept for Electronic Transfer Account or study compare

Switch Soft Starter – Principle and Working

A soft starter is any device which controls the acceleration of an electric motor by means of controlling the applied voltage.

Now let us have a brief recall of the need for having a starter for any motor.

An Induction motor has the ability to self start owing to the interaction between the rotating magnetic field flux and the rotor winding flux, causing a high rotor current as torque is increased. As a result the stator draws high current and by the time the motor reaches to full speed, a large amount of current (greater than the rated current) is drawn and this can cause heating up of the motor, eventually damaging it. To prevent this, motor starters are needed.

Motor starting can be in 3 ways

- Applying full load voltage at intervals of time: Direct On Line Starting

- Applying reduced voltage gradually : Star Delta Starter and Soft starter

- Applying part winding starting: Autotransformer starter

Defining Soft Starting

Now let us shift our particular attention to soft starting.

In technical terms, a soft starter is any device which reduces the torque applied to the electric motor. It generally consists of solid state devices like thyristors to control the application of supply voltage to the motor. The starter works on the fact that the torque is proportional to the square of the starting current, which in turn is proportional to the applied voltage. Thus the torque and the current can be adjusted by reducing the voltage at the time of starting the motor.

There can be two types of control using soft starter:

Open Control: A start voltage is applied with time, irrespective of the current drawn or the speed of the motor. For each phase two SCRs are connected back to back and the SCRs are conducted initially at a delay of 180 degrees during the respective half wave cycles (for which each SCR conducts). This delay is reduced gradually with time until the applied voltage ramps up to the full supply voltage. This is also known as Time Voltage Ramp System. This method is not relevant as it doesn’t actually control the motor acceleration.

Closed Loop Control: Any of the motor output characteristics like the current drawn or the speed is monitored and the starting voltage is modified accordingly to get the required response. The current in each phase is monitored and if it exceeds a certain set point, the time voltage ramp is halted.

Thus basic principle of soft starter is by controlling the conduction angle of the SCRs the application of supply voltage can be controlled.

2 Components of a basic soft starter

- Power switches like SCRs which need to be phase controlled such that they are applied for each part of the cycle. For a 3 phase motor, two SCRs are connected back to back for each phase. The switching devices need to be rated at least three times more than the line voltage.

- Control Logic using PID controllers or Microcontrollers or any other logic to control the application of gate voltage to the SCR, i.e. to control the firing angle of SCRs in order to make the SCR conduct at the required part of the supply voltage cycle.

Working Example of Electronic Soft Start System for 3 phase induction motor

The system consists of the following components.

- Two back to back SCRs for each phase, i.e. 6 SCRs in total.

- Control Logic circuitry in form of two comparators- LM324 and LM339 to produce the level and the ramp voltage and an opto-isolator to control the application of gate voltage to the each SCR in each phase.

A power supply circuitry to provide the required dc supply voltage.

The level voltage is generated using the comparator LM324 whose inverting terminal is fed using a fixed voltage source and the non inverting terminal is fed through a capacitor connected to the collector of an NPN transistor. The charging and discharging of the capacitor causes the output of the comparator to change accordingly and the voltage level to change from high to low. This output level voltage is applied to the non inverting terminal of another comparator LM339 whose inverting terminal is fed using a ramp voltage. This ramp voltage is produced using another comparator LM339 which compares the pulsating DC voltage applied at its inverting terminal to the pure DC voltage at its non inverting terminal and generates a zero voltage reference signal which is converted to a ramp signal by the charging and discharging of a electrolyte capacitor.

The 3rd comparator LM339 produces a High pulse width signal for every high level voltage, which decreases gradually as the level voltage reduces. This signal is inverted and applied to the Opto isolator, which provides gate pulses to the SCRs. As voltage level falls, the pulse width of the Opto isolator increases and more the pulse width, lesser is the delay and gradually the SCR is triggered without any delay. Thus by controlling the duration between the pulses or delay between applications of pulses, the firing angle of SCR is controlled and the application of supply current is controlled, thus controlling the motor output torque.

The whole process is actually an open loop control system where the time of application of gate triggering pulses to each SCR is controlled based on the how earlier the ramp voltage decreases from the level voltage.

Advantages of Soft Start

Now that we have learnt about how an electronic soft start system works, let us recollect few reasons why it is preferred over other methods.

- Improved Efficiency: The efficiency of soft starter system using solid state switches is more owing to the low on state voltage.

- Controlled startup: The starting current can be controlled smoothly by easily altering the starting voltage and this ensures smooth starting of the motor without any jerks.

- Controlled acceleration: Motor acceleration is controlled smoothly.

- Low Cost and size: This is ensured with the use of solid state switches.

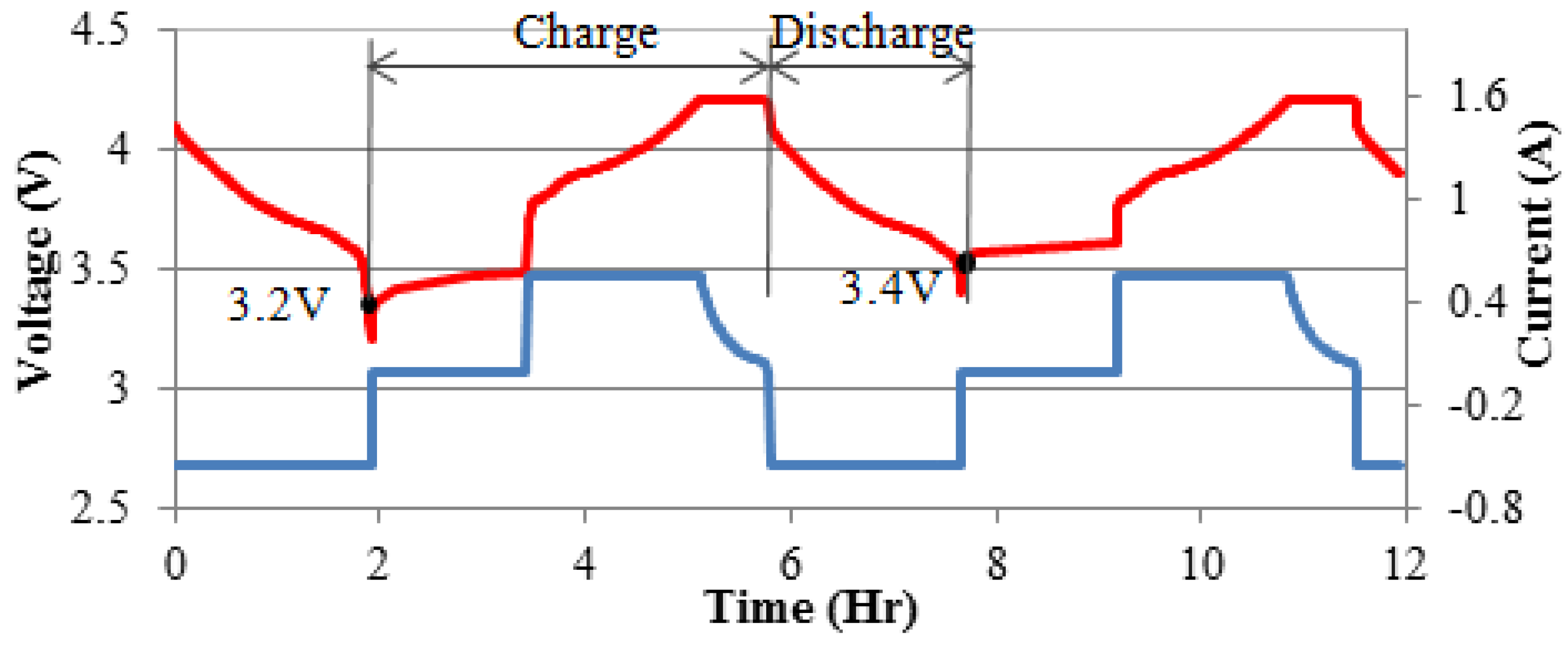

Battery Management Systems in Electric and Hybrid Vehicles

The battery management system (BMS) is a critical component of electric and hybrid electric vehicles. The purpose of the BMS is to guarantee safe and reliable battery operation. To maintain the safety and reliability of the battery, state monitoring and evaluation, charge control, and cell balancing are functionalities that have been implemented in BMS. As an electrochemical product, a battery acts differently under different operational and environmental conditions. The uncertainty of a battery’s performance poses a challenge to the implementation of these functions. This paper addresses concerns for current BMSs. State evaluation of a battery, including state of charge, state of health, and state of life, is a critical task for a BMS. Through reviewing the latest methodologies for the state evaluation of batteries, the future challenges for BMSs are presented and possible solutions are proposed as well.

Opinions on transactions demand

We have a list of opinions about transactions demand and you can also give us your opinion about it.We will see other people's opinions about transactions demand and we will find out what the others say about it.

Also, We will see opinions about other terms. Do not forget to leave our opinion about this topic and others related.

In the image below, you can see a graph with the evolution of the times that people look for transactions demand. And below it, you can see how many pieces of news have been created about transactions demand in the last years.

we can see the interest transactions demand has and the evolution of its popularity.

we can see the interest transactions demand has and the evolution of its popularity.

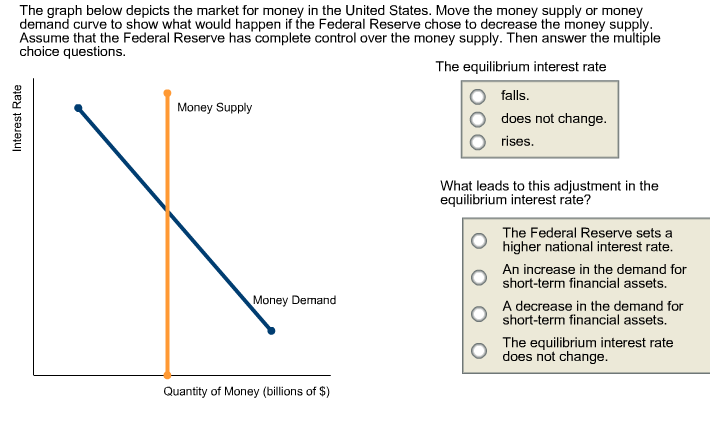

Demand, Supply, and Equilibrium in the Money Market

( Charge , Discharge, and Stabilization in the Money Market For Dollar Adapter )

we will explore the link between money markets, bond markets, and interest rates. We first look at the demand for money. The demand curve for money is derived like any other demand curve, by examining the relationship between the “price” of money (which, we will see, is the interest rate) and the quantity demanded, holding all other determinants unchanged. We then link the demand for money to the concept of money supply developed in the last chapter, to determine the equilibrium rate of interest. In turn, we show how changes in interest rates affect the macro economy.

The Demand for Money

In deciding how much money to hold, people make a choice about how to hold their wealth. How much wealth shall be held as money and how much as other assets? For a given amount of wealth, the answer to this question will depend on the relative costs and benefits of holding money versus other assets. The demand for money is the relationship between the quantity of money people want to hold and the factors that determine that quantity.

To simplify our analysis, we will assume there are only two ways to hold wealth: as money in a checking account, or as funds in a bond market mutual fund that purchases long-term bonds on behalf of its subscribers. A bond fund is not money. Some money deposits earn interest, but the return on these accounts is generally lower than what could be obtained in a bond fund. The advantage of checking accounts is that they are highly liquid and can thus be spent easily. We will think of the demand for money as a curve that represents the outcomes of choices between the greater liquidity of money deposits and the higher interest rates that can be earned by holding a bond fund. The difference between the interest rates paid on money deposits and the interest return available from bonds is the cost of holding money.

Motives for Holding Money

One reason people hold their assets as money is so that they can purchase goods and services. The money held for the purchase of goods and services may be for everyday transactions such as buying groceries or paying the rent, or it may be kept on hand for contingencies such as having the funds available to pay to have the car fixed or to pay for a trip to the doctor.

The transactions demand for money is money people hold to pay for goods and services they anticipate buying. When you carry money in your purse or wallet to buy a movie ticket or maintain a checking account balance so you can purchase groceries later in the month, you are holding the money as part of your transactions demand for money.

The money people hold for contingencies represents their precautionary demand for money. Money held for precautionary purposes may include checking account balances kept for possible home repairs or health-care needs. People do not know precisely when the need for such expenditures will occur, but they can prepare for them by holding money so that they’ll have it available when the need arises.

People also hold money for speculative purposes. Bond prices fluctuate constantly. As a result, holders of bonds not only earn interest but experience gains or losses in the value of their assets. Bondholders enjoy gains when bond prices rise and suffer losses when bond prices fall. Because of this, expectations play an important role as a determinant of the demand for bonds. Holding bonds is one alternative to holding money, so these same expectations can affect the demand for money.

John Maynard Keynes, who was an enormously successful speculator in bond markets himself, suggested that bondholders who anticipate a drop in bond prices will try to sell their bonds ahead of the price drop in order to avoid this loss in asset value. Selling a bond means converting it to money. Keynes referred to the speculative demand for money as the money held in response to concern that bond prices and the prices of other financial assets might change.

Of course, money is money. One cannot sort through someone’s checking account and locate which funds are held for transactions and which funds are there because the owner of the account is worried about a drop in bond prices or is taking a precaution. We distinguish money held for different motives in order to understand how the quantity of money demanded will be affected by a key determinant of the demand for money: the interest rate.

Interest Rates and the Demand for Money

The quantity of money people hold to pay for transactions and to satisfy precautionary and speculative demand is likely to vary with the interest rates they can earn from alternative assets such as bonds. When interest rates rise relative to the rates that can be earned on money deposits, people hold less money. When interest rates fall, people hold more money. The logic of these conclusions about the money people hold and interest rates depends on the people’s motives for holding money.

The quantity of money households want to hold varies according to their income and the interest rate; different average quantities of money held can satisfy their transactions and precautionary demands for money. To see why, suppose a household earns and spends $3,000 per month. It spends an equal amount of money each day. For a month with 30 days, that is $100 per day. One way the household could manage this spending would be to leave the money in a checking account, which we will assume pays zero interest. The household would thus have $3,000 in the checking account when the month begins, $2,900 at the end of the first day, $1,500 halfway through the month, and zero at the end of the last day of the month. Averaging the daily balances, we find that the quantity of money the household demands equals $1,500. This approach to money management, which we will call the “cash approach,” has the virtue of simplicity, but the household will earn no interest on its funds.

Consider an alternative money management approach that permits the same pattern of spending. At the beginning of the month, the household deposits $1,000 in its checking account and the other $2,000 in a bond fund. Assume the bond fund pays 1% interest per month, or an annual interest rate of 12.7%. After 10 days, the money in the checking account is exhausted, and the household withdraws another $1,000 from the bond fund for the next 10 days. On the 20th day, the final $1,000 from the bond fund goes into the checking account. With this strategy, the household has an average daily balance of $500, which is the quantity of money it demands. Let us call this money management strategy the “bond fund approach.”

Remember that both approaches allow the household to spend $3,000 per month, $100 per day. The cash approach requires a quantity of money demanded of $1,500, while the bond fund approach lowers this quantity to $500.

The bond fund approach generates some interest income. The household has $1,000 in the fund for 10 days (1/3 of a month) and $1,000 for 20 days (2/3 of a month). With an interest rate of 1% per month, the household earns $10 in interest each month ([$1,000 × 0.01 × 1/3] + [$1,000 × 0.01 × 2/3]). The disadvantage of the bond fund, of course, is that it requires more attention—$1,000 must be transferred from the fund twice each month. There may also be fees associated with the transfers.

Of course, the bond fund strategy we have examined here is just one of many. The household could begin each month with $1,500 in the checking account and $1,500 in the bond fund, transferring $1,500 to the checking account midway through the month. This strategy requires one less transfer, but it also generates less interest—$7.50 (= $1,500 × 0.01 × 1/2). With this strategy, the household demands a quantity of money of $750. The household could also maintain a much smaller average quantity of money in its checking account and keep more in its bond fund. For simplicity, we can think of any strategy that involves transferring money in and out of a bond fund or another interest-earning asset as a bond fund strategy.

Which approach should the household use? That is a choice each household must make—it is a question of weighing the interest a bond fund strategy creates against the hassle and possible fees associated with the transfers it requires. Our example does not yield a clear-cut choice for any one household, but we can make some generalizations about its implications.

First, a household is more likely to adopt a bond fund strategy when the interest rate is higher. At low interest rates, a household does not sacrifice much income by pursuing the simpler cash strategy. As the interest rate rises, a bond fund strategy becomes more attractive. That means that the higher the interest rate, the lower the quantity of money demanded.

Second, people are more likely to use a bond fund strategy when the cost of transferring funds is lower. The creation of savings plans, which began in the 1970s and 1980s, that allowed easy transfer of funds between interest-earning assets and checkable deposits tended to reduce the demand for money.

Some money deposits, such as savings accounts and money market deposit accounts, pay interest. In evaluating the choice between holding assets as some form of money or in other forms such as bonds, households will look at the differential between what those funds pay and what they could earn in the bond market. A higher interest rate in the bond market is likely to increase this differential; a lower interest rate will reduce it. An increase in the spread between rates on money deposits and the interest rate in the bond market reduces the quantity of money demanded; a reduction in the spread increases the quantity of money demanded.

Firms, too, must determine how to manage their earnings and expenditures. However, instead of worrying about $3,000 per month, even a relatively small firm may be concerned about $3,000,000 per month. Rather than facing the difference of $10 versus $7.50 in interest earnings used in our household example, this small firm would face a difference of $2,500 per month ($10,000 versus $7,500). For very large firms such as Toyota or AT&T, interest rate differentials among various forms of holding their financial assets translate into millions of dollars per day.

How is the speculative demand for money related to interest rates? When financial investors believe that the prices of bonds and other assets will fall, their speculative demand for money goes up. The speculative demand for money thus depends on expectations about future changes in asset prices. Will this demand also be affected by present interest rates?

If interest rates are low, bond prices are high. It seems likely that if bond prices are high, financial investors will become concerned that bond prices might fall. That suggests that high bond prices—low interest rates—would increase the quantity of money held for speculative purposes. Conversely, if bond prices are already relatively low, it is likely that fewer financial investors will expect them to fall still further. They will hold smaller speculative balances. Economists thus expect that the quantity of money demanded for speculative reasons will vary negatively with the interest rate.

The Demand Curve for Money

We have seen that the transactions, precautionary, and speculative demands for money vary negatively with the interest rate. Putting those three sources of demand together, we can draw a demand curve for money to show how the interest rate affects the total quantity of money people hold. The demand curve for money shows the quantity of money demanded at each interest rate, all other things unchanged. Such a curve is shown in Figure 25.7 “The Demand Curve for Money”. An increase in the interest rate reduces the quantity of money demanded. A reduction in the interest rate increases the quantity of money demanded.

The relationship between interest rates and the quantity of money demanded is an application of the law of demand. If we think of the alternative to holding money as holding bonds, then the interest rate—or the differential between the interest rate in the bond market and the interest paid on money deposits—represents the price of holding money. As is the case with all goods and services, an increase in price reduces the quantity demanded.

Other Determinants of the Demand for Money

We draw the demand curve for money to show the quantity of money people will hold at each interest rate, all other determinants of money demand unchanged. A change in those “other determinants” will shift the demand for money. Among the most important variables that can shift the demand for money are the level of income and real GDP, the price level, expectations, transfer costs, and preferences.

Real GDP

A household with an income of $10,000 per month is likely to demand a larger quantity of money than a household with an income of $1,000 per month. That relationship suggests that money is a normal good: as income increases, people demand more money at each interest rate, and as income falls, they demand less.

An increase in real GDP increases incomes throughout the economy. The demand for money in the economy is therefore likely to be greater when real GDP is greater.

The Price Level

The higher the price level, the more money is required to purchase a given quantity of goods and services. All other things unchanged, the higher the price level, the greater the demand for money.

Expectations

The speculative demand for money is based on expectations about bond prices. All other things unchanged, if people expect bond prices to fall, they will increase their demand for money. If they expect bond prices to rise, they will reduce their demand for money.

The expectation that bond prices are about to change actually causes bond prices to change. If people expect bond prices to fall, for example, they will sell their bonds, exchanging them for money. That will shift the supply curve for bonds to the right, thus lowering their price. The importance of expectations in moving markets can lead to a self-fulfilling prophecy.

Expectations about future price levels also affect the demand for money. The expectation of a higher price level means that people expect the money they are holding to fall in value. Given that expectation, they are likely to hold less of it in anticipation of a jump in prices.

Expectations about future price levels play a particularly important role during periods of hyperinflation. If prices rise very rapidly and people expect them to continue rising, people are likely to try to reduce the amount of money they hold, knowing that it will fall in value as it sits in their wallets or their bank accounts. Toward the end of the great German hyperinflation of the early 1920s, prices were doubling as often as three times a day. Under those circumstances, people tried not to hold money even for a few minutes—within the space of eight hours money would lose half its value!

Transfer Costs

For a given level of expenditures, reducing the quantity of money demanded requires more frequent transfers between nonmoney and money deposits. As the cost of such transfers rises, some consumers will choose to make fewer of them. They will therefore increase the quantity of money they demand. In general, the demand for money will increase as it becomes more expensive to transfer between money and nonmoney accounts. The demand for money will fall if transfer costs decline. In recent years, transfer costs have fallen, leading to a decrease in money demand.

Preferences

Preferences also play a role in determining the demand for money. Some people place a high value on having a considerable amount of money on hand. For others, this may not be important.

Household attitudes toward risk are another aspect of preferences that affect money demand. As we have seen, bonds pay higher interest rates than money deposits, but holding bonds entails a risk that bond prices might fall. There is also a chance that the issuer of a bond will default, that is, will not pay the amount specified on the bond to bondholders; indeed, bond issuers may end up paying nothing at all. A money deposit, such as a savings deposit, might earn a lower yield, but it is a safe yield. People’s attitudes about the trade-off between risk and yields affect the degree to which they hold their wealth as money. Heightened concerns about risk in the last half of 2008 led many households to increase their demand for money.

Figure 25.8 “An Increase in Money Demand” shows an increase in the demand for money. Such an increase could result from a higher real GDP, a higher price level, a change in expectations, an increase in transfer costs, or a change in preferences.

Figure 25.8 An Increase in Money Demand

An increase in real GDP, the price level, or transfer costs, for example, will increase the quantity of money demanded at any interest rate r, increasing the demand for money from D1 to D2. The quantity of money demanded at interest rate r rises from M to M′. The reverse of any such events would reduce the quantity of money demanded at every interest rate, shifting the demand curve to the left.

The Supply of Money

The supply curve of money shows the relationship between the quantity of money supplied and the market interest rate, all other determinants of supply unchanged. We have learned that the Fed, through its open-market operations, determines the total quantity of reserves in the banking system. We shall assume that banks increase the money supply in fixed proportion to their reserves. Because the quantity of reserves is determined by Federal Reserve policy, we draw the supply curve of money in Figure 25.9 “The Supply Curve of Money” as a vertical line, determined by the Fed’s monetary policies. In drawing the supply curve of money as a vertical line, we are assuming the money supply does not depend on the interest rate. Changing the quantity of reserves and hence the money supply is an example of monetary policy.

Equilibrium in the Market for Money

The money market is the interaction among institutions through which money is supplied to individuals, firms, and other institutions that demand money. Money market equilibrium occurs at the interest rate at which the quantity of money demanded is equal to the quantity of money supplied. Figure 25.10 “Money Market Equilibrium” combines demand and supply curves for money to illustrate equilibrium in the market for money. With a stock of money (M), the equilibrium interest rate is r.

Effects of Changes in the Money Market

A shift in money demand or supply will lead to a change in the equilibrium interest rate. Let’s look at the effects of such changes on the economy.

Changes in Money Demand

Suppose that the money market is initially in equilibrium at r1 with supply curve S and a demand curve D1 as shown in Panel (a) of Figure 25.11 “A Decrease in the Demand for Money”. Now suppose that there is a decrease in money demand, all other things unchanged. A decrease in money demand could result from a decrease in the cost of transferring between money and nonmoney deposits, from a change in expectations, or from a change in preferences1. Panel (a) shows that the money demand curve shifts to the left to D2. We can see that the interest rate will fall to r2. To see why the interest rate falls, we recall that if people want to hold less money, then they will want to hold more bonds. Thus, Panel (b) shows that the demand for bonds increases. The higher price of bonds means lower interest rates; lower interest rates restore equilibrium in the money market.

Figure 25.11 A Decrease in the Demand for Money

A decrease in the demand for money due to a change in transactions costs, preferences, or expectations, as shown in Panel (a), will be accompanied by an increase in the demand for bonds as shown in Panel (b), and a fall in the interest rate. The fall in the interest rate will cause a rightward shift in the aggregate demand curve from AD1 to AD2, as shown in Panel (c). As a result, real GDP and the price level rise.

Lower interest rates in turn increase the quantity of investment. They also stimulate net exports, as lower interest rates lead to a lower exchange rate. The aggregate demand curve shifts to the right as shown in Panel (c) from AD1 to AD2. Given the short-run aggregate supply curve SRAS, the economy moves to a higher real GDP and a higher price level.

An increase in money demand due to a change in expectations, preferences, or transactions costs that make people want to hold more money at each interest rate will have the opposite effect. The money demand curve will shift to the right and the demand for bonds will shift to the left. The resulting higher interest rate will lead to a lower quantity of investment. Also, higher interest rates will lead to a higher exchange rate and depress net exports. Thus, the aggregate demand curve will shift to the left. All other things unchanged, real GDP and the price level will fall.

Changes in the Money Supply

Now suppose the market for money is in equilibrium and the Fed changes the money supply. All other things unchanged, how will this change in the money supply affect the equilibrium interest rate and aggregate demand, real GDP, and the price level?

Suppose the Fed conducts open-market operations in which it buys bonds. This is an example of expansionary monetary policy. The impact of Fed bond purchases is illustrated in Panel (a) of Figure 25.12 “An Increase in the Money Supply”. The Fed’s purchase of bonds shifts the demand curve for bonds to the right, raising bond prices to Pb2. As we learned, when the Fed buys bonds, the supply of money increases. Panel (b) of Figure 25.12 “An Increase in the Money Supply” shows an economy with a money supply of M, which is in equilibrium at an interest rate of r1. Now suppose the bond purchases by the Fed as shown in Panel (a) result in an increase in the money supply to M′; that policy change shifts the supply curve for money to the right to S2. At the original interest rate r1, people do not wish to hold the newly supplied money; they would prefer to hold nonmoney assets. To reestablish equilibrium in the money market, the interest rate must fall to increase the quantity of money demanded. In the economy shown, the interest rate must fall to r2 to increase the quantity of money demanded to M′.

Figure 25.12 An Increase in the Money Supply

The Fed increases the money supply by buying bonds, increasing the demand for bonds in Panel (a) from D1 to D2 and the price of bonds to Pb2. This corresponds to an increase in the money supply to M′ in Panel (b). The interest rate must fall to r2to achieve equilibrium. The lower interest rate leads to an increase in investment and net exports, which shifts the aggregate demand curve from AD1 to AD2 in Panel (c). Real GDP and the price level rise.

The reduction in interest rates required to restore equilibrium to the market for money after an increase in the money supply is achieved in the bond market. The increase in bond prices lowers interest rates, which will increase the quantity of money people demand. Lower interest rates will stimulate investment and net exports, via changes in the foreign exchange market, and cause the aggregate demand curve to shift to the right, as shown in Panel (c), from AD1 to AD2. Given the short-run aggregate supply curve SRAS, the economy moves to a higher real GDP and a higher price level.

Open-market operations in which the Fed sells bonds—that is, a contractionary monetary policy—will have the opposite effect. When the Fed sells bonds, the supply curve of bonds shifts to the right and the price of bonds falls. The bond sales lead to a reduction in the money supply, causing the money supply curve to shift to the left and raising the equilibrium interest rate. Higher interest rates lead to a shift in the aggregate demand curve to the left.

As we have seen in looking at both changes in demand for and in supply of money, the process of achieving equilibrium in the money market works in tandem with the achievement of equilibrium in the bond market. The interest rate determined by money market equilibrium is consistent with the interest rate achieved in the bond market.

Key Takeaways

- People hold money in order to buy goods and services (transactions demand), to have it available for contingencies (precautionary demand), and in order to avoid possible drops in the value of other assets such as bonds (speculative demand).

- The higher the interest rate, the lower the quantities of money demanded for transactions, for precautionary, and for speculative purposes. The lower the interest rate, the higher the quantities of money demanded for these purposes.

- The demand for money will change as a result of a change in real GDP, the price level, transfer costs, expectations, or preferences.

- We assume that the supply of money is determined by the Fed. The supply curve for money is thus a vertical line. Money market equilibrium occurs at the interest rate at which the quantity of money demanded equals the quantity of money supplied.

- All other things unchanged, a shift in money demand or supply will lead to a change in the equilibrium interest rate and therefore to changes in the level of real GDP and the price level.

Try It!

In 2005 the Fed was concerned about the possibility that the United States was moving into an inflationary gap, and it adopted a contractionary monetary policy as a result. Draw a four-panel graph showing this policy and its expected results. In Panel (a), use the model of aggregate demand and aggregate supply to illustrate an economy with an inflationary gap. In Panel (b), show how the Fed’s policy will affect the market for bonds. In Panel (c), show how it will affect the demand for and supply of money. In Panel (d), show how it will affect the exchange rate. Finally, return to Panel (a) and incorporate these developments into your analysis of aggregate demand and aggregate supply, and show how the Fed’s policy will affect real GDP and the price level in the short run.

Case in Point: Money in Today’s World

Can Pac Swire – Hong Kong/ Travel Wallet – CC BY-NC 2.0.

The models of the money and bond markets presented in this chapter suggest that the Fed can control the interest rate by deciding on a money supply that would lead to the desired equilibrium interest rate in the money market. Yet, Fed policy announcements typically focus on what it wants the federal funds rate to be with scant attention to the money supply. Whereas throughout the 1990s, the Fed would announce a target federal funds rate and also indicate an expected change in the money supply, in 2000, when legislation requiring it to do so expired, it abandoned the practice of setting money supply targets.

Why the shift? The factors that have made focusing on the money supply as a policy target difficult for the past 25 years are first banking deregulation in the 1980s followed by financial innovations associated with technological changes—in particular the maturation of electronic payment and transfer mechanisms—thereafter.

Before the 1980s, M1 was a fairly reliable measure of the money people held, primarily for transactions. To buy things, one used cash, checks written on demand deposits, or traveler’s checks. The Fed could thus use reliable estimates of the money demand curve to predict what the money supply would need to be in order to bring about a certain interest rate in the money market.

Legislation in the early 1980s allowed for money market deposit accounts (MMDAs), which are essentially interest-bearing savings accounts on which checks can be written. MMDAs are part of M2. Shortly after, other forms of payments for transactions developed or became more common. For example, credit and debit card use has mushroomed (from $10.8 billion in 1990 to $30 billion in 2000), and people can pay their credit card bills, electronically or with paper checks, from accounts that are part of either M1 or M2. Another innovation of the last 20 years is the automatic transfer service (ATS) that allows consumers to move money between checking and savings accounts at an ATM machine, or online, or through prearranged agreements with their financial institutions. While we take these methods of payment for granted today, they did not exist before 1980 because of restrictive banking legislation and the lack of technological know-how. Indeed, before 1980, being able to pay bills from accounts that earned interest was unheard of.

Further blurring the lines between M1 and M2 has been the development and growing popularity of what are called retail sweep programs. Since 1994, banks have been using retail-sweeping software to dynamically reclassify balances as either checking account balances (part of M1) or MMDAs (part of M2). They do this to avoid reserve requirements on checking accounts. The software not only moves the funds but also ensures that the bank does not exceed the legal limit of six reclassifications in any month. In the last 10 years these retail sweeps rose from zero to nearly the size of M1 itself!

Such changes in the ways people pay for transactions and banks do their business have led economists to think about new definitions of money that would better track what is actually used for the purposes behind the money demand curve. One notion is called MZM, which stands for “money zero maturity.” The idea behind MZM is that people can easily use any deposits that do not have specified maturity terms to pay for transactions, as these accounts are quite liquid, regardless of what classification of money they fall into. Some research shows that using MZM allows for a stable picture of the money market. Until more agreement has been reached, though, we should expect the Fed to continue to downplay the role of the money supply in its policy deliberations and to continue to announce its intentions in terms of the federal funds rate.

Source: Pedre Teles and Ruilin Zhou, “A Stable Money Demand: Looking for the Right Monetary Aggregate,” Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago Economic Perspectives 29 (First Quarter, 2005): 50–59.

Answer to Try It! Problem

In Panel (a), with the aggregate demand curve AD1, short-run aggregate supply curve SRAS, and long-run aggregate supply curve LRAS, the economy has an inflationary gap of Y1 − YP. The contractionary monetary policy means that the Fed sells bonds—a rightward shift of the bond supply curve in Panel (b), which decreases the money supply—as shown by a leftward shift in the money supply curve in Panel (c). In Panel (b), we see that the price of bonds falls, and in Panel (c) that the interest rate rises. A higher interest rate will reduce the quantity of investment demanded. The higher interest rate also leads to a higher exchange rate, as shown in Panel (d), as the demand for dollars increases and the supply decreases. The higher exchange rate will lead to a decrease in net exports. As a result of these changes in financial markets, the aggregate demand curve shifts to the left to AD2 in Panel (a). If all goes according to plan (and we will learn in the next chapter that it may not!), the new aggregate demand curve will intersect SRAS and LRAS at YP.

1In this chapter we are looking only at changes that originate in financial markets to see their impact on aggregate demand and aggregate supply. Changes in the price level and in real GDP also shift the money demand curve, but these changes are the result of changes in aggregate demand or aggregate supply and are considered in more advanced courses in macroeconomics.

Loanable Funds

The Market for Loanable Funds

When a firm decides to expand its capital stock, it can finance its purchase of capital in several ways. It might already have the funds on hand. It can also raise funds by selling shares of stock, as we discussed in a previous module. When a firm sells stock, it is selling shares of ownership of the firm. It can borrow the funds for the capital from a bank. Another option is to issue and sell its own bonds. A bond is a promise to pay back a certain amount at a certain time. When a firm borrows from a bank or sells bonds, of course, it accepts a liability—it must make interest payments to the bank or the owners of its bonds as they come due.

Regardless of the method of financing chosen, a critical factor in the firm’s decision on whether to acquire and hold capital and on how to finance the capital is the interest rate. The role of the interest rate is obvious when the firm issues its own bonds or borrows from a bank. But even when the firm uses its own funds to purchase the capital, it is forgoing the option of lending those funds directly to other firms by buying their bonds or indirectly by putting the funds in bank accounts, thereby allowing the banks to lend the funds. The interest rate gives the opportunity cost of using funds to acquire capital rather than putting the funds to the best alternative use available to the firm.

The interest rate is determined in a market in the same way that the price of potatoes is determined in a market: by the forces of demand and supply. The market in which borrowers (demanders of funds) and lenders (suppliers of funds) meet is the loanable funds market.

We will simplify our model of the role that the interest rate plays in the demand for capital by ignoring differences in actual interest rates that specific consumers and firms face in the economy. For example, the interest rate on credit cards is higher than the mortgage rate of interest, and large, established companies can borrow funds or issue bonds at lower interest rates than new, start-up companies can. Interest rates that firms face depend on a variety of factors, such as riskiness of the loan, the duration of the loan, and the costs of administering the loan. However, since we will focus on general tendencies that cause interest rates to rise or fall and since the various interest rates in the economy tend to move up and down together, the conclusions we reach about the market for loanable funds and how firms and consumers respond to interest rate changes will still be valid.

The Demand for Loanable Funds

In the previous section we learned that a firm’s decision to acquire and keep capital depends on the net present value of the capital in question, which in turn depends on the interest rate. The lower the interest rate, the greater the amount of capital that firms will want to acquire and hold, since lower interest rates translate into more capital with positive net present values. The desire for more capital means, in turn, a desire for more loanable funds. Similarly, at higher interest rates, less capital will be demanded, because more of the capital in question will have negative net present values. Higher interest rates therefore mean less funding demanded.

Figure 13.2. The Demand and Supply of Loanable Funds. At lower interest rates, firms demand more capital and therefore more loanable funds. The demand for loanable funds is downward-sloping. The supply of loanable funds is generally upward-sloping. The equilibrium interest rate, rE, will be found where the two curves intersect.

Thus the demand for loanable funds is downward-sloping, like the demand for virtually everything else, as shown in Figure 13.2. The lower the interest rate, the more capital firms will demand. The more capital that firms demand, the greater the funding that is required to finance it.

The Supply of Loanable Funds

Lenders are consumers or firms that decide that they are willing to forgo some current use of their funds in order to have more available in the future. Lenders supply funds to the loanable funds market. In general, higher interest rates make the lending option more attractive.

For consumers, however, the decision is a bit more complicated than it is for firms. In examining consumption choices across time, economists think of consumers as having an expected stream of income over their lifetimes. It is that expected income that defines their consumption possibilities. The problem for consumers is to determine when to consume this income. They can spend less of their projected income now and thus have more available in the future. Alternatively, they can boost their current spending by borrowing against their future income.

Saving is income not spent on consumption. (We shall ignore taxes in this analysis.) Dissaving occurs when consumption exceeds income during a period. Dissaving means that the individual’s saving is negative. Dissaving can be financed either by borrowing or by using past savings. Many people, for example, save in preparation for retirement and then dissave during their retirement years.

Saving adds to a household’s wealth. Dissaving reduces it. Indeed, a household’s wealth is the sum of the value of all past saving less all past dissaving.

We can think of saving as a choice to postpone consumption. Because interest rates are a payment paid to people who postpone their use of wealth, interest rates are a kind of reward paid to savers. Will higher interest rates encourage the behavior they reward? The answer is a resounding “maybe.” Just as higher wages might not increase the quantity of labor supplied, higher interest rates might not increase the quantity of saving. The problem, once again, lies in the fact that the income and substitution effects of a change in interest rates will pull in opposite directions.

Consider a hypothetical consumer, choices concerning the timing of consumption by assuming that there are only two periods: the present period is period 0, and the next is period 1. Suppose the interest rate is 8% and his income in both periods is expected to be $30,000.

You could, of course, spend $30,000 in period 0 and $30,000 in period 1. In that case, his saving equals zero in both periods. But he has alternatives. He could, for example, spend more than $30,000 in period 0 by borrowing against his income for period 1. Alternatively, he could spend less than $30,000 in period 0 and use his saving—and the interest he earns on that saving—to boost his consumption in period 1. If, for example, he spends $20,000 in period 0, his saving in period 0 equals $10,000. He will earn $800 interest on that saving, so he will have $40,800 to spend in the next period.

Suppose the interest rate rises to 10%. The increase in the interest rate has boosted the price of current consumption. Now for every $1 he spends in period 0 he gives up $1.10 in consumption in period 1, instead of $1.08, which was the amount that would have been given up in consumption in period 1 when the interest rate was 8%. A higher price produces a substitution effect that reduces an activity—You will spend less in the current period due to the substitution effect. The substitution effect of a higher interest rate thus boosts saving. But the higher interest rate also means that he earns more income on his saving. Consumption in the current period is a normal good, so an increase in income can be expected to increase current consumption. But an increase in current consumption implies a reduction in saving. The income effect of a higher interest rate thus tends to reduce saving. Whether You savings will rise or fall in response to a higher interest rate depends on the relative strengths of the substitution and income effects.

To see how an increase in interest rates might reduce saving, You has decided that his goal is to have $40,800 to spend in period 1. At an interest rate of 10%, he can reduce his saving below $10,000 and still achieve his goal of having $40,800 to spend in the next period. The income effect of the increase in the interest rate has reduced his saving, and consequently his desire to supply funds to the loanable funds market.

Because changes in interest rates produce substitution and income effects that pull saving in opposite directions, we cannot be sure what will happen to saving if interest rates change. The combined effect of all consumers’ and firms’ decisions, however, generally leads to an upward-sloping supply curve for loanable funds, as shown in Figure 13.2. That is, the substitution effect usually dominates the income effect.

The equilibrium interest rate is determined by the intersection of the demand and supply curves in the market for loanable funds.

Capital and the Loanable Funds Market

If the quantity of capital demanded varies inversely with the interest rate, and if the interest rate is determined in the loanable funds market, then it follows that the demand for capital and the loanable funds market are interrelated. Because the acquisition of new capital is generally financed in the loanable funds market, a change in the demand for capital leads to a change in the demand for loanable funds—and that affects the interest rate. A change in the interest rate, in turn, affects the quantity of capital demanded on any demand curve.

The relationship between the demand for capital and the loanable funds market thus goes both ways. Changes in the demand for capital affect the loanable funds market, and changes in the loanable funds market can affect the quantity of capital demanded.

Changes in the Demand for Capital and the Loanable Funds Market

Figure 13.3 suggests how an increased demand for capital by firms will affect the loanable funds market, and thus the quantity of capital firms will demand. In Panel (a) the initial interest rate is r1. At r1 in Panel (b) K1units of capital are demanded (on curve D1). Now suppose an improvement in technology increases the marginal product of capital, shifting the demand curve for capital in Panel (b) to the right to D2. Firms can be expected to finance the increased acquisition of capital by demanding more loanable funds, shifting the demand curve for loanable funds to D2 in Panel (a). The interest rate thus rises to r2. Consequently, in the market for capital the demand for capital is greater and the interest rate is higher. The new quantity of capital demanded is K2on demand curve D2.

Figure 13.3. Loanable Funds and the Demand for Capital. The interest rate is determined in the loanable funds market, and the quantity of capital demanded varies with the interest rate. Thus, events in the loanable funds market and the demand for capital are interrelated. If the demand for capital increases to D2 in Panel (b), the demand for loanable funds is likely to increase as well. Panel (a) shows the result in the loanable funds market—a shift in the demand curve for loanable funds from D1 to D2 and an increase in the interest rate from r1 to r2. At r2, the quantity of capital demanded will be K2, as shown in Panel (b).

Changes in the Loan able Funds Market and the Demand for Capital

Events in the loan able funds market can also affect the quantity of capital firms will hold. Suppose, for example, that consumers decide to increase current consumption and thus to supply fewer funds to the loan able funds market at any interest rate. This change in consumer preferences shifts the supply curve for loan able funds in Panel (a) of Figure 13.4 from S1 to S2 and raises the interest rate to r2. If there is no change in the demand for capital D1, the quantity of capital firms demand falls to K2 in Panel (b).

Figure 13.4. A Change in the Loanable Funds Market and the Quantity of Capital Demanded. A change that begins in the loanable funds market can affect the quantity of capital firms demand. Here, a decrease in consumer saving causes a shift in the supply of loanable funds from S1 to S2 in Panel (a). Assuming there is no change in the demand for capital, the quantity of capital demanded falls from K1 to K2 in Panel (b).

Our model of the relationship between the demand for capital and the loanable funds market thus assumes that the interest rate is determined in the market for loanable funds. Given the demand curve for capital, that interest rate then determines the quantity of capital firms demand.

Table 13.2 shows that a change in the quantity of capital that firms demand can begin with a change in the demand for capital or with a change in the demand for or supply of loan able funds. A change in the demand for capital affects the demand for loan able funds and hence the interest rate in the loan able funds market. The change in the interest rate leads to a change in the quantity of capital demanded. Alternatively, a change in the loan able funds market, which leads to a change in the interest rate, causes a change in quantity of capital demanded.

| Table 13.2 Two Routes to Changes in the Quantity of Capital Demanded | |

| A change originating in the capital market | A change originating in the loanable funds market |

| 1. A change in the demand for capital leads to… | 1. A change in the demand for or supply of loanable funds leads to … |

| 2.…a change in the demand for loanable funds, which leads to… | 2.…a change in the interest rate, which leads to… |

| 3.…a change in the interest rate, which leads to… | 3.…a change in the quantity of capital demanded. |

| 4.…a change in the quantity of capital demanded. |

A change in the quantity of capital that firms demand can begin with a change in the demand for capital or with a change in the demand or supply of loan able funds.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- The net present value (NPV) of an investment project is equal to the present value of its expected revenues minus the present value of its expected costs. Firms will want to undertake those investments for which the NPV is greater than or equal to zero.

- The demand curve for capital shows that firms demand a greater quantity of capital at lower interest rates. Among the forces that can shift the demand curve for capital are changes in expectations, changes in technology, changes in the demands for goods and services, changes in relative factor prices, and changes in tax policy.

- The interest rate is determined in the market for loanable funds. The demand curve for loanable funds has a negative slope; the supply curve has a positive slope.

- Changes in the demand for capital affect the loanable funds market, and changes in the loanable funds market affect the quantity of capital demanded.

Case in Point: The Net Present Value of an MBA

An investment in human capital differs little from an investment in capital—one acquires an asset that will produce additional income over the life of the asset. One’s education produces—or it can be expected to produce—additional income over one’s working career. The estimated marginal revenue product for each year is the difference between the salaries students earned with a degree versus what they would have earned without it. The NPV is then computed using

The estimates given here show the NPV of an MBA over the first seven years of work after receiving the degree.

New Electronic Trading Systems in the Foreign Exchange Markets

The foreign exchange market can be divided in two segments: the interbank market and the customer market. Two advances in trading technology, electronic brokers in the interbank market and internet trading for customers, have significantly changed the structure of the foreign exchange market. we explain the functioning of electronic brokers and internet trading and discuss the economic consequences.

Bid–ask spread Difference between the best buy price (ask) and best sell

price (bid). The initiator of a trade buys at the ask and sells at the lower

bid price. The spread is a measure of transaction costs. The buy price is

also called the “offer.”

Broker Brokers match dealers in the interbank market without being

a party to the transactions themselves and without taking positions

(cf. dealer).

Call market A market where all traders trade at the same time when

called upon.

Counterparty credit risk The risk that the market participant on the other

side of a transaction will default. Due to the large trade sizes in foreign

exchange markets, credit risk is an important issue.

Dealer A person employed by a bank whose primary business is entering

into transactions on both sides of wholesale financial markets and

seeking profits by taking risks in these markets (cf. broker).

Dealer market Market where orders for execution pass to an inter-

mediary (dealer) for execution.

Interbank market The market where dealers trade exclusively with each

other, either bilaterally or through brokers.

Limit order Order to buy a specified quantity up to a maximum price or

sell subject to a minimum price (cf. market order).

Liquidity Characteristic of a market where transactions do not exces-

sively move prices. It is also easy to have a trade effected quickly

without a long search for counterparties (“immediacy”). Liquid markets

usually have low bid–ask spreads, high volume, and (relatively) low

volatility.

Market maker Dealer ready to quote buy and sell prices upon request.

The market maker provides immediacy (liquidity services) to the market

and receives compensation through the spread.There is no formal oblig-

ation to quote tight spreads; rather, market making is governed by

reciprocity.

Market order Order to buy (or sell) a specified quantity at the best pre-

vailing price (cf. limit order).

Order-driven market Market where prices are determined by an order

execution algorithm from participants sending firm buy and sell orders,

which are incorporated into the limit order book (cf. quote-driven or

dealer market).

Order flow Signed flow of transactions. The transaction is given a

positive (negative) sign if the initiator of the transactions is buying

(selling).

Price discovery Determination of prices in a market. Incorporation of

information into prices

Quote-driven market Refers to a market where market makers post bid

and ask quotes upon bilateral request. In the interbank market, these

prices are on a take-it-or-leave-it basis (cf. order-driven market).

Transparency Ability of market participants to observe trade information

in a timely fashion.

I. INTRODUCTION

The 1990s gave us what might prove to be the two biggest changes in

foreign exchange market structure since World War II: electronic brokers

were introduced into the interbank market in 1992, and in the late 1990s

the Internet became available as a trading channel for customers.What are

the consequences for the market of these innovations? Is there any reason

to believe that these technological developments have influenced the

market in any significant way? Do not dealers in the foreign exchange

market still fulfill their function as liquidity providers and aggregate infor-

mation in their price setting? And, do not basic macroeconomic variables

still drive exchange rates, irrespective of trading technology?

In an ideal world with perfect information, these changes to the institu-

tions of trading probably would not matter that much at the macro-

economic level. In such a world, exchange rates would be determined by

expectations regarding macroeconomic fundamentals like inflation, pro-

ductivity growth, and interest rates. Exchange rates will be efficient asset

prices when all market participants observe these fundamentals and agree

on how they influence exchange rates. Furthermore, provision of liquidity

would be much less risky than in a situation with imperfect information.

However, as empirical evidence has shown all too clearly,models of an ideal

world with perfect information do not hold, at least not for horizons shorter

than a year or so.

The micro structure approach to foreign exchange has made some

promising steps toward solving some of these puzzles .This approach differs from the traditional macroeconomic approach by allowing for imperfect information and heterogeneous agents and, thereby,leaving a role for trading institutions as such. In such a world, technologi-cal changes such as the introduction of electronic brokers and Internet trading may be significant because they change the structure of the market.A different market structure changes the game played between the market participants. This may influence information aggregation capabili- ties and incentives for liquidity provision and, thereby, different aspects of market quality like efficiency (price discovery), liquidity, and transaction costs .

We are interested in understanding market structure because

a well-functioning foreign exchange market is important for the macro-

economy. This chapter considers the impact of technological advances on

the foreign exchange market by focusing on these properties of market

quality.

The new economy and foreign exchange markets is a vast subject. We

limit ourselves to the two major innovations in trading technology because

trading institutions are an important part of a financial market’s structure.

Furthermore, several studies show that trading is important for the

determination of exchange rates. There is particular focus on a property

of market structure called transparency, i.e., how much of the trading

process market participants can observe. Because trading is an important

determinant of exchange rates, observation of the trading process is

important to enable dealers to set the “correct” exchange rates. On a more

general level, transparency relates to how efficiently dealers can aggregate

information.

There are of course many other uses of information and communication

technology (ICT) that have obviously influenced the markets that we do

not address here. These include information providers such as Reuters

and Bloomberg, computers’ calculation capabilities and the importance

for option trading, and of course network technologies and computers in

general. Two other technological innovations deserving special atten-

tion that we do not consider are the newly started settlement service

CLS Bank (Continuous Linked Settlement), which went live on September

9, 2002, and the netting technology FXNet. The former links all participat

ing countries’ payment systems for real-time settlement. With such a

system in place in 1974, the famous Bankhaus Herstatt default would

never had happened. FXNet is a technology for netting out gross lia-

bilities. Both are very important for the handling of counterparty credit

risk .

THE STRUCTURE OF FOREIGN EXCHANGE

MARKETS

Before we discuss electronic brokers and Internet trading, we need an

overview of the general structure of the foreign exchange market so as to

be able to understand the impact of these new trading institutions.Although

electronic brokers were undoubtedly the most significant structural change

in the 1990s, the general description given here is valid for the structure

both before and after the introduction of electronic brokers.The reason is

that brokers were present in the market before electronic brokers were

introduced. The introduction of Internet trading, on the other hand, is still

very recent, but it may prove to be the most significant structural shift of

the first decade of the twenty-first century. This shift has the potential to

overthrow the general structure of the market completely, a point that we

come back to in Section V.

A. INFORMATION AND AGENTS

The foreign exchange market is the oldest and largest financial market

in the world, with $1200 billion changing hands every day (April 2001).1

These trades can be divided into interbank trades and customer trades, rep-

resenting the two segments of the market. In the interbank market, trading

is either direct (bilateral or taking place between dealers) or brokered

(interdealer trades). Prior to the advent of the Internet, customers traded

only with banks. We could have added customer-to-customer Internet-

based trading sites, but we feel it is too early to pay them the same atten-

tion as the three methods already mentioned (interbank, both direct and

brokered, and customer–bank). In the 1990s, the market was often divided

into three groups: customers, dealers, and brokers. However, as brokering

becomes more and more electronic and also is open to customers through

the Internet, we feel that it is more natural to focus on two main groups of

traders: customers and dealers. The customers are the ultimate end-users of

currency, and they typically make the largest single trades. Customers may

be central banks,governments, importers and exporters of goods, and finan-

cial institutions like hedge funds.

Important characteristics of the foreign exchange market are that cus-

tomers do not have access to the interbank market and that they do not

trade with each other (except on the customer-to-customer sites mentioned earlier, which we return to later). The trading that takes place with cus-

tomers is private information for the banks, and dealers stress the impor-

tance of seeing customer flows. An interesting question is what kind of

information this trading may reveal. For understanding the concept of infor-

mation in the foreign exchange market, we need to add some details to what

we mean by information, and Lyons (2002) suggests the description given

in Table 1. The starting point is the expression of an asset price as the dis-

counted expected value. Information may concern the expected value, the

payoff-relevant part, or the discount rate (including the risk premium).

In the upper left corner of Table 1, concentrated payoff-relevant infor-

mation, or information on risk-neutral valuations, is the kind of private

information that is typical in equity markets. In the case of foreign

exchange, it probably does not constitute the main motivation for

information-based trading. Changes in central banks’ interest rates are too

infrequent and too shrouded in secrecy for private information about these

rates to be a major driver of trading. However, private information about

interventions is a possible candidate because central banks sometimes

perform their interventions through particular banks. Bettina Peiers found

that the exchange rate changes made by Deutsche Bank were leading the

rates of other banks through rumors of interventions.

Rather, Lyons (2002) suggests that it is the lower row in Table 1 that is

most relevant in foreign exchange markets. The information that needs to

be aggregated by the market is not concentrated on a few people,but rather

dispersed among many. In their 2002 paper, Martin D. D. Evans and Lyons

present a model where customer trading represents portfolio shifts and

signals changes in risk premiums . A risk premium arises as the compensation necessary to

induce others to take the other side of the portfolio shift.This risk premium

must be a permanent change in exchange rates because the new holders of

currency must want to continue holding the currency.Their empirical results

confirm this .

INSTITUTIONS

The market structure has not always been like the present structure.

Prior to telecommunications, trading in foreign exchange markets could be

described as a centralized call market. Trading in foreign exchange can be

traced back to ancient times, when foreign exchange trading was a way to

circumvent the ban on usury. In the sixteenth century, trading in foreign

exchange occurred every third month at fairs in the Genoa area, each of

which lasted for 8 days.2However,telecommunications changed the general

structure of the foreign exchange market, and it has been more or less unal-

tered from the early 1930s up to the present.3Drawing on the theory of the

microstructure of financial markets, we can describe the current interbank

foreign exchange market as follows:

1. Trading is decentralized across several locations, as opposed to

centralized on an exchange as is the case in many equity markets.

2. There is continuous trading around the clock, as opposed to only

when called upon as in a call market.

3. There are several dealers that provide liquidity, as opposed to the

specialist on the NYSE floor in earlier days, for example.

4. Liquidity is both quote-driven, i.e., created by quoting bid and ask

prices in response to trading initiatives (market making or dealer

market), and order-driven, i.e., by entering limit orders with brokers

(auction market).

5. The market is relatively opaque, i.e., has low transparency compared

with many equity markets.

The introduction of telecommunications allowed decentralized trade of

the asset foreign exchange, as is most natural. Banks want to be present

where the customers are, and because an exchange rate is the relative price

of two assets from two different countries, it is natural to have a decen-

tralized market. Given that customers are in different time zones and may

have an interest in the same asset, say $, trading must also be continuous

around the clock. Finally, given the geographical pattern of customers and

the fact that several banks serve them, it is natural to have a number of

dealers acting as liquidity providers in each currency pair. The decentral-

ized structure also makes it very difficult to regulate foreign exchange

trading, and the market structure has therefore evolved endogenously.

These factors, together with the lack of regulatory disclosure requirements,

mean that the foreign exchange markets are characterized by low

transparency.

All of this has economic consequences.Low transparency means that few

of the dispersed signals that order flow may reveal will be observed by a

single dealer. In a centralized call market,which is more transparent, infor-

mation aggregation will typically be faster and more accurate. The lack of

regulation is also important. Disclosure requirements are imposed on

equity markets so that more trading, and hence more information, is

observed by the market participants.As will be discussed later, the trading

institutions also have implications for risk sharing.

INTERBANK TRADING OPTIONS

Foreign exchange trading typically follows a sequence. Customers’

trading is the primary source of currency demand, and the sequence starts

with a customer contacting her bank with a wish to trade (dealers never

take the initiative). The bank acts as market maker and gives quotes to the

customer. Customers do not have access to the interbank market, so an

exporter cannot contact his counterparty or the counterparty’s bank

directly. For a customer, trading with the counterparty directly involves

credit risk, which could be handled more efficiently by a bank.A dealer in

the bank then turns to the interbank market to cover the customer trade.

Interbank trading actually accounts for between 60% and 80% of the total

volume of foreign exchange trading, and we will come back to this issue in

the next section because it is closely related to trading institutions.

In the interbank market, the dealer has several options, as illustrated by

the 2 ¥2 matrix in Table 2. In a multiple-dealer market, the dealer may

choose to provide liquidity as a market maker and give quotes when con-

tacted by other dealers (incoming trade), or he may trade on other market

makers’ quotes (outgoing trade). Because this is bilateral, it is often called

direct trading. Furthermore, the interbank market is a hybrid market in the

sense that liquidity can be provided both through making markets and by

entering limit orders with brokers.The brokers announce the best bid and

ask prices,and trading on these is a market order. Brokered trades are often

called indirect trading.

The information signal in trading is connected to the action of the most

active part in the trade, often called the initiator or aggressor (outgoing

trade). If the aggressor buys (sells), we say that it is a positive (negative)

order flow, so order flow is just a transaction with a sign. How is this infor-

mative? Think of the portfolio shift model of Evans and Lyons mentioned

in the discussion of Table 1. If the aggressor buys,that could be because she

is covering a position after a customer purchase (portfolio shift into that

currency). Alternatively, think of the proposition that order flow reveals

information about other dealers’ expectations. Then a purchase on behalf

of the aggressor could be a signal, with noise, that the aggressor believes

the currency is undervalued. In both cases, the positive order flow signals

that the exchange rate should appreciate.

TRANSPARENCY

As mentioned earlier, transparency is low in foreign exchange markets

compared to most equity markets. There are many forms of transparency:

pretrade and posttrade transparency, transparency of prices or trades, and

transparency with respect to whether the customers or only the dealers can

observe the trading process. To start with the last of these, in the foreign

exchange markets only the dealers can observe anything other than their

own trading. The trades with customers that initiate the trading sequence

are only observed by the bank that receives the order and, hence, are

private information for the banks. In the interbank market, trades that are

made directly between two dealers are only observed by the two dealers.

The lack of disclosure requirements also ensures that these trades will not

be observed by other dealers after the trade is made. Indirect trading is

more transparent because the price and sign (buying or selling by the

aggressor) of the last trades are observable. In this sense, trading through

brokers is what determines the level of trade transparency. This level has

evolved endogenously as a result of dealers’ indirect trading.

Price transparency is higher than trade transparency, but until recently

customers’ ability to see prices was less than that of dealers.However, com-

pared to many equity markets with indirect trading, transparency is still low.

In many equity markets a trader may be able to see the identity of the best

bid and ask and often also a part of or the entire order book (all the other

limit orders). In the case of a trade, both the size and the identity of the

counterparties are revealed in many equity markets.

DIRECT TRADING AND VOICE BROKERS

In this section, we provide a further elaboration on the working of the

interbank market prior to the electronic brokers by discussing how indirect

and direct trading actually functions and affects dealers’ behavior.As men-

tioned earlier, the trading institutions have been more or less unaltered for

a long time, perhaps since the early 1930s when the first telephone brokers

started. The composition of direct versus indirect trading has changed over

time, however. For telephone brokers, the main innovation came in the

1960s when brokers started operating through private telephone networks.

These are installed free of charge in banks by brokers. The broker

announces the best (limit order) bid and ask prices over intercoms at the

dealers’ desk. If the dealer wants to trade at a limit order, i.e., submit a

market order, he picks up the phone with the direct line and just says