International Finance Regulation provides recommendations and suggestions from the perspective of a leading

global authority .

when I worked at a bank and international insurance around 2002 to 2003, I was involved in a lot of capital turnover techniques and capital movements for businesses, especially companies that registered their businesses on the stock exchange floor - every company always needed fresh funds to expand their companies and cover the eroded working capital so that the activities of the company continue to move forward and obtain benefits that may be shared to develop the company into other business units, generally the company's business movement is not far from its core business . capital movements in each company are listed on the exchange floor and when I was dealing capital, it was not easy for someone or many people to have more money to be able to inject their capital into a company, usually before dealing, the owner of the money always asked the company's financial statements within 4 up to 5 years, of course this data and information can be reached through electronic information about the condition of the company whose name is listed on the stock exchange floor or who has gone public. there are many concepts in buying a few shares for a buyer : there are those who buy stocks when the stock price goes up or blue chip companies are usually companies in the transportation and energy sector there are also those who buy shares when the company's stock price drops the reason when it is cheap why not buy because there is a saying as long as the smoke from the factory is still rising, it is still possible for the company to expand. thus the state also gets fresh funds by selling government bonds to everyone who wants to buy bonds or sell government-owned assets in part to private or foreign with the aim that their assets can run smoothly and share risks. that's a glimpse of my experience at international banks and insurance where at that time all dealing processes had used the financial information electronics process as well as in all insurance processes were online with various currencies that could be used especially the dollar as a fresh fund.

Lord Jesus Bless US and Family

Gen. Mac Tech

INTERNATIONAL FINANCE

The International Financial System which takes care of the electronic transfer of international money orders. system work uses electronic data interchange (EDI) to send international money order data electronically, using sophisticated data encryption techniques to ensure the integrity of the data sent over the postal network. The modern international Finance must be provide electronic domestic money order services.

The modern international Finance is a complete management that responds perfectly to the needs of Posts in the electronic transfer of money orders especially at a time when the money transfer market is becoming increasingly competitive.

Its Gross National Index (GNI) based costing structure and low transaction-tax enables a very fast return on investment. The goal of the The modern international Finance is to provide postal enterprises with reliable, secure, and timely electronic financial services, which in turn allows Posts to be more competitive in the global marketplace. this now The modern international Finance not only handles all phases of international and domestic money processing but also provides advanced features that facilitate cash management and accounting .

| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

| ||||

|

| The modern international Finance also supports a variety of money order and fund transfer services, from ordinary cash-to-cash orders to urgent wired transfers. On the network, any transfer of data is protected by strong software encryption techniques. Network members are part of a Public Key Infrastructure (PKI) operated by the PTC. The processing operational front-end is run as a Web application. This is specifically adapted for easy deployment over an Intranet or even over the Internet. it must be can easily be interfaced with an existing application, such as a counter operations system. In addition, the system user interface can be localized into any language. |

Electronic Finance : A New Approach to Financial Sector Development ?

In recent years, electronic finance, especially online banking, and brokerage services, has reshaped the financial landscape. This must be and have to reviews these developments, and analyzes their implications for consumers, governments, and financial service providers. First, it reviews the e-finance (r)evolution in emerging, and other markets, and projects its future growth. It then analyzes e-finance impact on the structure of, and competition in the financial services industry. After that, it assesses how e-finance, and globalization more generally, affects financial sector policies in emerging markets, including the need for changes in the approach to financial sector development. The paper then examines governments' changing role in the financial sector, and identifies opportunities that e-finance offers countries to leapfrog. Finally, the paper includes for policymakers, and others involved in financial sector reform in emerging markets, detailed information, and Web links on public policy activities related to e-finance.

Growth of electronics funds transfer (EFT) is examined in the context of the internationalization of the banking and finance industry. EFT has grown in response to the internationalization of the industry and in turn has facilitated its development. Reasons for the geographical diversification of transnational banks and other financial institutions are discussed. The growing interdependence between international financial centres of New York and London is highlighted as is the emergence of Asian financial centres of Tokyo, Hong Kong and Singapore. Various types of international EFT systems are examined including SWIFT and leased networks operated by transnational banks. In addition, entry of non banking institutions into the international EFT area is considered. Competition between banks as well as between banks and non-banking institutions is examined in the context of these EFT developments.

Circle raises fresh funds; plans dollar-pegged token

With the fresh funding, the Boston-based startup will push plans to create a new cryptocurrency pegged to the price of the US dollar . The unit, called “Circle US$ Coin”, will be backed by real reserves of US dollars and will aim to provide an efficient way for businesses and consumers to transfer value, “A price-stable medium of exchange and store of value is missing, and badly needed in order for global financial interoperability to function reliably and consistently, “Circle can be an issuer of US dollar coin, Square (a payments company) could be an issuer. If I got US dollar coins from Circle, I could transmit those to another digital wallet for an issuer,such as Tether token (USDT) which is linked to US dollar reserves and tied to the price of the US dollar. But the cryptotoken has faced criticism for its opacity. Circle believes the existing fiat-backed cryptocurrency approaches “have lacked financial and operational transparency”and then on the reserves backing the USDC coin, and conduct strict anti-money laundering and other checks on individuals and companies looking to buy and redeem the new coins.

The Destruction of Money: Who Does It, Why, When, and How?

Think about money being created. A furiously spinning printing press might come to mind. Now imagine money being destroyed. Do you think of a three-story shredder, a bonfire, a wide blue recycling bin?

You might have noticed that it's pretty hard to find any cash printed much earlier than the 1990s in circulation. Just as more money is constantly being created, it's also constantly being destroyed. Who are the destroyers of money, and how do they do it?

In order to explain money destruction, we have to define what we mean by money destruction. For example, are we talking about money being eliminated, its very presence disappearing from the economy? Or are we talking about when money is physically destroyed but replaced with newer, crisper currency? Let's consider both questions.

When Money Disappears

You probably know that the Federal Reserve controls the money supply, the technical term for the amount of money in the economy. When the money supply expands, money flows into the financial system. When the money supply contracts, money drains out of the financial system. But how does the money actually disappear?

The Fed expands the money supply through a couple of methods. For simplicity, let's consider "security purchasing." When the Fed wants to expand the money supply, it buys a security -- let's call it Asset A -- from a bank. Then it electronically transfers money to that bank. There is now additional money in the financial system that the bank can use to provide loans.

The nice part about being the Fed is that it doesn't actually need to mail a box of dollar bills to pay for these securities. Instead, it creates a "reserve balance" liability on its balance sheet. The transaction is completely electronic. No hard currency changes hands.

Then, when the Fed is ready to reduce monetary supply, it sells Asset A. This puts the security back into the financial market and reduces money in the system, again electronically. Is that money destroyed?

On the one hand, the money no longer exists in the financial system. On the other hand, it was only there temporarily in the first place. When the Fed gets that money back, it merely reduces the size of its reserve balance liability. In a sense, money is only "created" during an expansionary cycle electronically, through an accounting mechanism. It's then "destroyed" in a similar, but opposite, accounting entry.

When Currency Is Physically Destroyed

Obviously, not all money is electronic. Just look at your wallet. Bills and coins are destroyed every day. There are three destroyers of money, and they're the same ones who create and regulate it.

(1) The Bureau of Engraving and Printing and (2) The U.S. Mint

The U.S. Bureau of Engraving and Printing creates all of the nation's bills, while the U.S. mint creates its coins. But they also destroy money.

Banks and individuals will hand over "mutilated" bills and coins to these agencies. They then validate its authenticity and issue a Treasury check in return. The Bureau of Engraving and Printing receives around 25,000 mutilated currency redemption claims annually. Each bill is shredded and sent to waste energy facilities for disposal.

(3) The Federal Reserve

The great regulator of money distributes currency through its 30 Federal Reserve Bank Cash Offices, after receiving it from the Bureau of Engraving and Printing. But it also destroys currency that it wants taken out of circulation and replaced with fresh money.

The Fed is diligent about keeping our currency fit since a torn or mangled bill can't go through an ATM, a vending machine, or another electronic reader. As a result, the average life of each bill is surprisingly short:

- $1 bills: 3.7 years

- $5 bills: 3.4 years

- $10 bills: 3.4 years

- $20 bills: 5.1 years

- $50 bills: 12.6 years

- $100 bills: 8.9 years

Overall the average life for all bills is about five years.The Fed occasionally has some reason for accelerating the rate at which money is taken out of the system, like when a new bill design is introduced. But generally, a banknote's fitness determines how long it remains in the financial system.

So how does the Fed know if a bill is fit for commerce? It processes currency submitted to its Federal Reserve banks by the public to check for fitness. The cash offices uses a sophisticated high-speed sorting machine called the "Banknote processing system 3000," manufactured by German firm Giesecke & Devrient. The BPS 3000 has sophisticated sensors that check bills for authenticity and defects like graffiti, dog ears, tears, excessive soiling, and limpness. If a bill is counterfeit, it is sent to the Secret Service. But if it's merely unfit by the Fed's standards, then the machine shreds it. Those shredded notes are sent to landfills or packaged and provided as souvenirs to the public on Federal Reserve Bank tours.

How much money does the Fed destroy? In 2010, its cash offices destroyed 5.95 billion notes. In 2009, that number was even larger at 6.05 billion notes. A large proportion of those notes were $1 and $20 bills, which are the workhorses of the American economy. In 2010, 2.6 billion $1 bills were destroyed.

Those dollars in your wallet won't last forever. Eventually, they will likely end up shredded and replaced by newer, crisper banknotes. But don't fret: although money is being destroyed on a regular basis, it's being crated even more quickly. Currency grows at a relatively stable rate each year. So the net amount of money out there doesn't generally decline. In that sense, money is really never destroyed.

The Study Case is World Bank and Globalization: A Brief Overview

The World Bank, based in Washington, is a multilateral institution that lends money to governments and government agencies for development projects. For more than twenty years, the Bank has imposed stringent conditions, known as "Structural Adjustment Programs," on recipient countries, forcing them to adopt reforms such as deregulation of capital markets, privatization of state companies, and downsizing of public programs for social welfare. Privatization of water supplies, fees for public schools and hospitals, and privatization of public pensions are among the most controversial Bank reforms. While the Bank insists that "fighting poverty" is its first priority, many critics believe instead that it is responsible for rising poverty. Many also criticize its cozy relationship with Wall Street and the United States Treasury Department. The stormy resignation of World Bank Vice President and Chief Economist Joseph Stiglitz in late 1999, and his subsequent public comments, suggest that the Bank is not as benign as it claims to be.

A perennial challenge facing all of the world's countries, regardless of their level of economic development, is achieving financial stability, economic growth, and higher living standards. There are many different paths that can be taken to achieve these objectives, and every country's path will be different given the distinctive nature of national economies and political systems.

|

Yet, based on experiences throughout the world, several basic principles seem to underpin greater prosperity. These include investment (particularly foreign direct investment), the spread of technology, strong institutions, sound macroeconomic policies, an educated workforce, and the existence of a market economy. Furthermore, a common denominator which appears to link nearly all high-growth countries together is their participation in, and integration with, the global economy.

There is substantial evidence, from countries of different sizes and different regions, that as countries "globalize" their citizens benefit, in the form of access to a wider variety of goods and services, lower prices, more and better-paying jobs, improved health, and higher overall living standards. It is probably no mere coincidence that over the past 20 years, as a number of countries have become more open to global economic forces, the percentage of the developing world living in extreme poverty—defined as living on less than $1 per day—has been cut in half.

As much as has been achieved in connection with globalization, there is much more to be done. Regional disparities persist: while poverty fell in East and South Asia, it actually rose in sub-Saharan Africa. The UN's Human Development Report notes there are still around 1 billion people surviving on less than $1 per day—with 2.6 billion living on less than $2 per day. Proponents of globalization argue that this is not because of too much globalization, but rather too little. And the biggest threat to continuing to raise living standards throughout the world is not that globalization will succeed but that it will fail. It is the people of developing economies who have the greatest need for globalization, as it provides them with the opportunities that come with being part of the world economy.

These opportunities are not without risks—such as those arising from volatile capital movements. The International Monetary Fund works to help economies manage or reduce these risks, through economic analysis and policy advice and through technical assistance in areas such as macroeconomic policy, financial sector sustainability, and the exchange-rate system.

The risks are not a reason to reverse direction, but for all concerned—in developing and advanced countries, among both investors and recipients—to embrace policy changes to build strong economies and a stronger world financial system that will produce more rapid growth and ensure that poverty is reduced.

The following is a brief overview to help guide anyone interested in gaining a better understanding of the many issues associated with globalization.

What is Globalization?

Economic "globalization" is a historical process, the result of human innovation and technological progress. It refers to the increasing integration of economies around the world, particularly through the movement of goods, services, and capital across borders. The term sometimes also refers to the movement of people (labor) and knowledge (technology) across international borders. There are also broader cultural, political, and environmental dimensions of globalization.

The term "globalization" began to be used more commonly in the 1980s, reflecting technological advances that made it easier and quicker to complete international transactions—both trade and financial flows. It refers to an extension beyond national borders of the same market forces that have operated for centuries at all levels of human economic activity—village markets, urban industries, or financial centers.

There are countless indicators that illustrate how goods, capital, and people, have become more globalized.

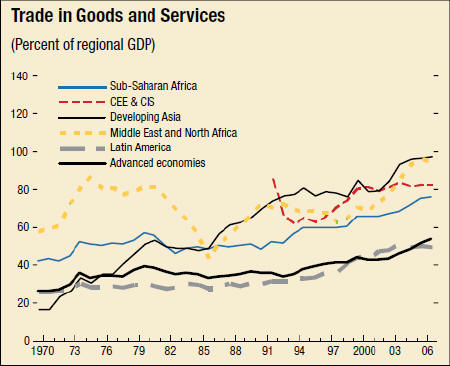

- The value of trade (goods and services) as a percentage of world GDP increased from 42.1 percent in 1980 to 62.1 percent in 2007.

- Foreign direct investment increased from 6.5 percent of world GDP in 1980 to 31.8 percent in 2006.

- The stock of international claims (primarily bank loans), as a percentage of world GDP, increased from roughly 10 percent in 1980 to 48 percent in 2006.1

- The number of minutes spent on cross-border telephone calls, on a per-capita basis, increased from 7.3 in 1991 to 28.8 in 2006.2

- The number of foreign workers has increased from 78 million people (2.4 percent of the world population) in 1965 to 191 million people (3.0 percent of the world population) in 2005.

The growth in global markets has helped to promote efficiency through competition and the division of labor—the specialization that allows people and economies to focus on what they do best. Global markets also offer greater opportunity for people to tap into more diversified and larger markets around the world. It means that they can have access to more capital, technology, cheaper imports, and larger export markets. But markets do not necessarily ensure that the benefits of increased efficiency are shared by all. Countries must be prepared to embrace the policies needed, and, in the case of the poorest countries, may need the support of the international community as they do so.

The broad reach of globalization easily extends to daily choices of personal, economic, and political life. For example, greater access to modern technologies, in the world of health care, could make the difference between life and death. In the world of communications, it would facilitate commerce and education, and allow access to independent media. Globalization can also create a framework for cooperation among nations on a range of non-economic issues that have cross-border implications, such as immigration, the environment, and legal issues. At the same time, the influx of foreign goods, services, and capital into a country can create incentives and demands for strengthening the education system, as a country's citizens recognize the competitive challenge before them.

Perhaps more importantly, globalization implies that information and knowledge get dispersed and shared. Innovators—be they in business or government—can draw on ideas that have been successfully implemented in one jurisdiction and tailor them to suit their own jurisdiction. Just as important, they can avoid the ideas that have a clear track record of failure. Joseph Stiglitz, a Nobel laureate and frequent critic of globalization, has nonetheless observed that globalization "has reduced the sense of isolation felt in much of the developing world and has given many people in the developing world access to knowledge well beyond the reach of even the wealthiest in any country a century ago."3

International Trade

A core element of globalization is the expansion of world trade through the elimination or reduction of trade barriers, such as import tariffs. Greater imports offer consumers a wider variety of goods at lower prices, while providing strong incentives for domestic industries to remain competitive. Exports, often a source of economic growth for developing nations, stimulate job creation as industries sell beyond their borders. More generally, trade enhances national competitiveness by driving workers to focus on those vocations where they, and their country, have a competitive advantage. Trade promotes economic resilience and flexibility, as higher imports help to offset adverse domestic supply shocks. Greater openness can also stimulate foreign investment, which would be a source of employment for the local workforce and could bring along new technologies—thus promoting higher productivity.

Restricting international trade—that is, engaging in protectionism—generates adverse consequences for a country that undertakes such a policy. For example, tariffs raise the prices of imported goods, harming consumers, many of which may be poor. Protectionism also tends to reward concentrated, well-organized and politically-connected groups, at the expense of those whose interests may be more diffuse (such as consumers). It also reduces the variety of goods available and generates inefficiency by reducing competition and encouraging resources to flow into protected sectors.

Developing countries can benefit from an expansion in international trade. Ernesto Zedillo, the former president of Mexico, has observed that, "In every case where a poor nation has significantly overcome its poverty, this has been achieved while engaging in production for export markets and opening itself to the influx of foreign goods, investment, and technology."4 And the trend is clear. In the late 1980s, many developing countries began to dismantle their barriers to international trade, as a result of poor economic performance under protectionist polices and various economic crises. In the 1990s, many former Eastern bloc countries integrated into the global trading system and developing Asia—one of the most closed regions to trade in 1980—progressively dismantled barriers to trade. Overall, while the average tariff rate applied by developing countries is higher than that applied by advanced countries, it has declined significantly over the last several decades.

The implications of globalized financial markets

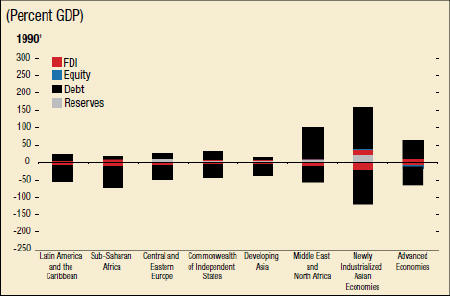

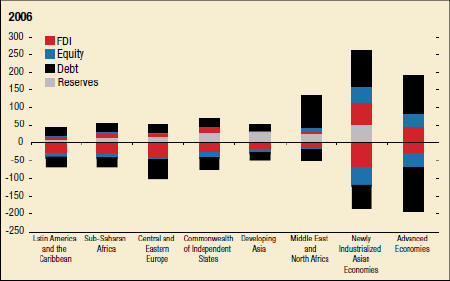

The world's financial markets have experienced a dramatic increase in globalization in recent years. Global capital flows fluctuated between 2 and 6 percent of world GDP during the period 1980-95, but since then they have risen to 14.8 percent of GDP, and in 2006 they totaled $7.2 trillion, more than tripling since 1995. The most rapid increase has been experienced by advanced economies, but emerging markets and developing countries have also become more financially integrated. As countries have strengthened their capital markets they have attracted more investment capital, which can enable a broader entrepreneurial class to develop, facilitate a more efficient allocation of capital, encourage international risk sharing, and foster economic growth.

Cross-Border Assets and Liabilities (Percent GDP)

1Data series bein in 1995 for central and eastern Europe and the Commonweatlth of Independent States.

Yet there is an energetic debate underway, among leading academics and policy experts, on the precise impact of financial globalization. Some see it as a catalyst for economic growth and stability. Others see it as injecting dangerous—and often costly—volatility into the economies of growing middle-income countries.

A recent paper by the IMF's Research Department takes stock of what is known about the effects of financial globalization.5 The analysis of the past 30 years of data reveals two main lessons for countries to consider.

First, the findings support the view that countries must carefully weigh the risks and benefits of unfettered capital flows. The evidence points to largely unambiguous gains from financial integration for advanced economies. In emerging and developing countries, certain factors are likely to influence the effect of financial globalization on economic volatility and growth: countries with well-developed financial sectors, strong institutions, sounds macroeconomic policies, and substantial trade openness are more likely to gain from financial liberalization and less likely to risk increased macroeconomic volatility and to experience financial crises. For example, well-developed financial markets help moderate boom-bust cycles that can be triggered by surges and sudden stops in international capital flows, while strong domestic institutions and sound macroeconomic policies help attract "good" capital, such as portfolio equity flows and FDI.

The second lesson to be drawn from the study is that there are also costs associated with being overly cautious about opening to capital flows. These costs include lower international trade, higher investment costs for firms, poorer economic incentives, and additional administrative/monitoring costs. Opening up to foreign investment may encourage changes in the domestic economy that eliminate these distortions and help foster growth.

Looking forward, the main policy lesson that can be drawn from these results is that capital account liberalization should be pursued as part of a broader reform package encompassing a country's macroeconomic policy framework, domestic financial system, and prudential regulation. Moreover, long-term, non-debt-creating flows, such as FDI, should be liberalized before short-term, debt-creating inflows. Countries should still weigh the possible risks involved in opening up to capital flows against the efficiency costs associated with controls, but under certain conditions (such as good institutions, sound domestic and foreign policies, and developed financial markets) the benefits from financial globalization are likely to outweigh the risks.

Globalization, income inequality, and poverty

As some countries have embraced globalization, and experienced significant income increases, other countries that have rejected globalization, or embraced it only tepidly, have fallen behind. A similar phenomenon is at work within countries—some people have, inevitably, been bigger beneficiaries of globalization than others.

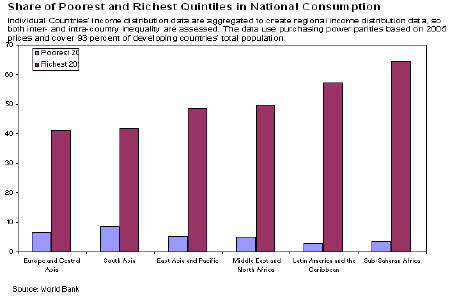

Over the past two decades, income inequality has risen in most regions and countries. At the same time, per capita incomes have risen across virtually all regions for even the poorest segments of population, indicating that the poor are better off in an absolute sense during this phase of globalization, although incomes for the relatively well off have increased at a faster pace. Consumption data from groups of developing countries reveal the striking inequality that exists between the richest and the poorest in populations across different regions.

As discussed in the October 2007 issue of the World Economic Outlook, one must keep in mind that there are many sources of inequality. Contrary to popular belief, increased trade globalization is associated with a decline in inequality. The spread of technological advances and increased financial globalization—and foreign direct investment in particular—have instead contributed more to the recent rise in inequality by raising the demand for skilled labor and increasing the returns to skills in both developed and developing countries. Hence, while everyone benefits, those with skills benefit more.

It is important to ensure that the gains from globalization are more broadly shared across the population. To this effect, reforms to strengthen education and training would help ensure that workers have the appropriate skills for the evolving global economy. Policies that broaden the access of finance to the poor would also help, as would further trade liberalization that boosts agricultural exports from developing countries. Additional programs may include providing adequate income support to cushion, but not obstruct, the process of change, and also making health care less dependent on continued employment and increasing the portability of pension benefits in some countries.

Equally important, globalization should not be rejected because its impact has left some people unemployed. The dislocation may be a function of forces that have little to do with globalization and more to do with inevitable technological progress. And, the number of people who "lose" under globalization is likely to be outweighed by the number of people who "win."

Martin Wolf, the Financial Times columnist, highlights one of the fundamental contradictions inherent in those who bemoan inequality, pointing out that this charge amounts to arguing "that it would be better for everybody to be equally poor than for some to become significantly better off, even if, in the long run, this will almost certainly lead to advances for everybody."6

Indeed, globalization has helped to deliver extraordinary progress for people living in developing nations. One of the most authoritative studies of the subject has been carried out by World Bank economists David Dollar and Aart Kraay.7 They concluded that since 1980, globalization has contributed to a reduction in poverty as well as a reduction in global income inequality. They found that in "globalizing" countries in the developing world, income per person grew three-and-a-half times faster than in "non-globalizing" countries, during the 1990s. In general, they noted, "higher growth rates in globalizing developing countries have translated into higher incomes for the poor." Dollar and Kraay also found that in virtually all events in which a country experienced growth at a rate of two percent or more, the income of the poor rose.

Critics point to those parts of the world that have achieved few gains during this period and highlight it as a failure of globalization. But that is to misdiagnose the problem. While serving as Secretary-General of the United Nations, Kofi Annan pointed out that "the main losers in today's very unequal world are not those who are too much exposed to globalization. They are those who have been left out."8 A recent BBC World Service poll found that on average 64 percent of those polled—in 27 out of 34 countries—held the view that the benefits and burdens of "the economic developments of the last few years" have not been shared fairly. In developed countries, those who have this view of unfairness are more likely to say that globalization is growing too quickly. In contrast, in some developing countries, those who perceive such unfairness are more likely to say globalization is proceeding too slowly.

As individuals and institutions work to raise living standards throughout the world, it will be critically important to create a climate that enables these countries to realize maximum benefits from globalization. That means focusing on macroeconomic stability, transparency in government, a sound legal system, modern infrastructure, quality education, and a deregulated economy.

Myths about globalization

No discussion of globalization would be complete without dispelling some of the myths that have been built up around it.

Downward pressure on wages: Globalization is rarely the primary factor that fosters wage moderation in low-skilled work conducted in developed countries. As discussed in a recent issue of the World Economic Outlook, a more significant factor is technology. As more work can be mechanized, and as fewer people are needed to do a given job than in the past, the demand for that labor will fall, and as a result the prevailing wages for that labor will be affected as well.

The "race to the bottom": Globalization has not caused the world's multinational corporations to simply scour the globe in search of the lowest-paid laborers. There are numerous factors that enter into corporate decisions on where to source products, including the supply of skilled labor, economic and political stability, the local infrastructure, the quality of institutions, and the overall business climate. In an open global market, while jurisdictions do compete with each other to attract investment, this competition incorporates factors well beyond just the hourly wage rate. According to the UN Information Service, the developed world hosts two-thirds of the world's inward foreign direct investment. The 49 least developed countries—the poorest of the developing countries—account for around 2 per cent of the total inward FDI stock of developing countries.

Nor is it true that multinational corporations make a consistent practice of operating sweatshops in low-wage countries, with poor working conditions and substandard wages. While isolated examples of this can surely be uncovered, it is well established that multinationals, on average, pay higher wages than what is standard in developing nations, and offer higher labor standards.9

Globalization is irreversible: In the long run, globalization is likely to be an unrelenting phenomenon. But for significant periods of time, its momentum can be hindered by a variety of factors, ranging from political will to availability of infrastructure. Indeed, the world was thought to be on an irreversible path toward peace and prosperity early in the early 20th century, until the outbreak of Word War I. That war, coupled with the Great Depression, and then World War II, dramatically set back global economic integration. And in many ways, we are still trying to recover the momentum we lost over the past 90 years or so.

That fragility of nearly a century ago still exists today—as we saw in the aftermath of September 11th, when U.S. air travel came to a halt, financial markets shut down, and the economy weakened. The current turmoil in financial markets also poses great difficulty for the stability and reliability of those markets, as well as for the global economy. Credit market strains have intensified and spread across asset classes and banks, precipitating a financial shock that many have characterized as the most serious since the 1930s. These episodes are reminders that a breakdown in globalization—meaning a slowdown in the global flows of goods, services, capital, and people—can have extremely adverse consequences.

Openness to globalization will, on its own, deliver economic growth: Integrating with the global economy is, as economists like to say, a necessary, but not sufficient, condition for economic growth. For globalization to be able to work, a country cannot be saddled with problems endemic to many developing countries, from a corrupt political class, to poor infrastructure, and macroeconomic instability.

The shrinking state: Technologies that facilitate communication and commerce have curbed the power of some despots throughout the world, but in a globalized world governments take on new importance in one critical respect, namely, setting, and enforcing, rules with respect to contracts and property rights. The potential of globalization can never be realized unless there are rules and regulations in place, and individuals to enforce them. This gives economic actors confidence to engage in business transactions.

Further undermining the idea of globalization shrinking states is that states are not, in fact, shrinking. Public expenditures are, on average, as high or higher today as they have been at any point in recent memory. And among OECD countries, government tax revenue as a percentage of GDP increased from 25.5 percent in 1965 to 36.6 percent in 2006.

The future of globalization

Like a snowball rolling down a steep mountain, globalization seems to be gathering more and more momentum. And the question frequently asked about globalization is not whether it will continue, but at what pace.

A disparate set of factors will dictate the future direction of globalization, but one important entity—sovereign governments—should not be overlooked. They still have the power to erect significant obstacles to globalization, ranging from tariffs to immigration restrictions to military hostilities. Nearly a century ago, the global economy operated in a very open environment, with goods, services, and people able to move across borders with little if any difficulty. That openness began to wither away with the onset of World War I in 1914, and recovering what was lost is a process that is still underway. Along the process, governments recognized the importance of international cooperation and coordination, which led to the emergence of numerous international organizations and financial institutions (among which the IMF and the World Bank, in 1944).

Indeed, the lessons included avoiding fragmentation and the breakdown of cooperation among nations. The world is still made up of nation states and a global marketplace. We need to get the right rules in place so the global system is more resilient, more beneficial, and more legitimate. International institutions have a difficult but indispensable role in helping to bring more of globalization's benefits to more people throughout the world. By helping to break down barriers—ranging from the regulatory to the cultural—more countries can be integrated into the global economy, and more people can seize more of the benefits of globalization.

XO__XO Investment Fund

What is an 'Investment Fund'

An investment fund is a supply of capital belonging to numerous investors used to collectively purchase securities

while each investor retains ownership and control of his own shares. An investment fund provides a broader selection of investment opportunities,

greater management expertise and lower investment fees than investors might be able to obtain on their own.

Types of investment funds include mutual funds, exchange-traded funds, money market funds and hedge funds.

BREAKING DOWN 'Investment Fund'

With investment funds, individual investors do not make decisions about how a fund's assets should be invested. They simply choose a fund based on its goals, risk, fees and other factors. A fund manager oversees the fund and decides which securities it should hold, in what quantities and when the securities should be bought and sold. An investment fund can be broad-based, such as an index fund that tracks the S&P 500, or it can be tightly focused, such as an ETF that invests only in small technology stocks.

While investment funds in various forms have been around for many years, the Massachusetts Investors Trust Fund is generally considered the first open-end mutual fund in the industry. The fund, investing in a mix of large-cap stocks, launched in 1924.

Open-end vs. Closed-end

The majority of investment fund assets belong to open-end mutual funds. These funds issue new shares as investors add money to the pool, and retire shares as investors redeem. These funds are typically priced just once at the end of the trading day.

Closed-end funds trade more similarly to stocks than open-end funds. Closed-end funds are managed investment funds that issue a fixed number of shares, and trade on an exchange. While a net asset value (NAV) for the fund is calculated, the fund trades based on investor supply and demand. Therefore, a closed-end fund may trade at a premium or a discount to its NAV.

Emergence of ETFs

Exchange-traded funds (ETFs) emerged as an alternative to mutual funds for traders who wanted more flexibility with their investment funds. Similar to closed-end funds, ETFs trade on exchanges, and are priced and available for trading throughout the business day. Many mutual funds, such as the Vanguard 500 Index Fund, have ETF counterparts. The Vanguard S&P 500 ETF is essentially the same fund, but came be bought and sold intraday. ETFs frequently have the additional advantage of slightly lower expense ratios than their mutual fund equal.

The first ETF, the SPDR S&P 500 ETF, debuted in 1993. ETFs have more than $4.4 trillion in assets under management, as of September 2017.

Investment Funds: Hedge Funds

A hedge fund is another type of fund that pairs stocks it wants to short (bet will decrease) with stocks it expects to go up in order to decrease the potential for loss. Hedge funds also tend to invest in riskier assets in addition to stocks, bonds, ETFs, commodities and alternative assets. These include derivatives such as futures and options that may also be purchased with leverage, or borrowed money.

XO___XO XXX When do mutual funds say no to fresh fund inflows?

However, established companies often need to raise extra funds as well.

And if a company requires a cash injection to expand its existing operations, protect its market share, develop new businesses, or buy another company, it may require more than its retained earnings.

In that case, the company's directors have two options: borrow the money, or raise more equity.

Taking on debt requires the company's managers to have a reasonable expectation of steady cash flow to make regular interest repayments, plus it has the risk that investors may feel the company is too highly geared (has too much debt in relation to its shareholders funds), which may weigh heavily on the share price.

Taken to the extreme, high debt magnifies the risk of bankruptcy, which is precisely what happened in the late 1980s when rising interest rates crippled some of Australia's highest-profile companies. Banks stopped lending during the 2008/09 financial crisis, which forced many listed Australian companies to raise equity funds at vastly discounted prices in order to remain afloat.

Interest is a tax-deductible expense, however, and less equity raised means less of the company is being shared around. So debt certainly has its attractions.

Corporate finance strategists charge big money to decide on the best way for companies to raise funds and, despite years of effort, research remains inconclusive on the ideal capital structure to maximise a corporation's value to shareholders.

It's a complex area that spans issues as diverse as taxation, interest expense, public relations, and overall financial management, and that's probably all that needs to be said about it for now.

If a company chooses to issue fresh equity, it's again faced with two main options: give all existing shareholders the right to buy more shares; or offer shares in a "placement" to a group of people, or an institution.

It also has the third, less common, option of creating a specialised spin-off company, which gives investors the opportunity to direct funds toward a specific aspect of the business, usually with high growth prospects.

Assessing a rights issue

One of the most common ways companies raise new equity is through a rights issue. This means offering existing shareholders the right to buy further shares - in proportion to their existing holdings - at a specified price.

Naturally, the issue price for the rights has to be a little less than the current market price to make the deal worthwhile.

If you hold shares for any length of time, you'll soon come across this method of raising funds. At first, it might sound like something for nothing - after all, you pay nothing for the "rights", which usually have a market value and can even be sold - and you get to buy shares at less than the current market price. However, rights issues aren't always as generous as they might sound.

Before you worry about the numbers, your first consideration is why the company is undertaking a rights issue: what does it plan to do with the money? If it's raising extra capital to buy an expanding business that will greatly enhance its competitive positioning and earning power, then the rights issue may be good news indeed.

However, if the company has to pay out virtually all of its profits just to maintain its dividend to shareholders and keep the share price up, a rights issue may be lurking around the corner for less glamorous reasons.

It could be that earnings are weakening so much that the company needs that extra cash just to maintain its core business. It could be a good reason to look for better value elsewhere.

This is the number one factor in assessing any rights issue - where's the money going? To growth or stagnation? The next thing you need to check is the mathematics of the deal. It's usually quite straightforward, so let's run through a quick example.

Say you have 1000 shares in Quicksand Constructions Limited currently trading at $2 each and the company has 1 million shares on issue. You therefore own $2000 worth of Quicksand or 0.1 per cent of the company. The Quicksand directors identify a growth opportunity and make a 1-for-4 rights issue at the discounted price of $1.60.

You get the right to buy one new share at $1.60 for every four shares you own. That's a substantial discount to the current share price, so the issue sounds attractive. But is it? And how much are your rights really "worth"? If you take up the offer, your share holding will include:

1000 shares at the current market price - $2.00 $2000

250 new shares at the "rights" price - $1.60 $400

Cost of all your shares $2400

So what's the average cost of all your shares after the rights issue?

So what does this mean?

Because the shares bought via rights are cheaper than the current market price (and because free lunches are hard to come by), these lower-priced shares theoretically drag down the market price "post rights" to $1.92.

This means you lose 8 cents per share (a total of $80) on the original shares you held, because the share price is 8 cents lower. But you get the same amount back by exercising your right to buy 250 shares at $1.60 instead of the expected market price of $1.92. Exercising your rights also means that your shareholding as a percentage of issued capital remains the same.

While this is essential in understanding that rights are often not what they're cracked up to be, in reality, the share price may not behave this way at all.

As discussed earlier, investors will judge the rights issue according to what use the company is putting the money, and whether it is expected to increase earnings over time.

If, in the Quicksand example, the share price did not fall to $1.92 but managed to hold firm at $2 because the project it would finance was so compelling, investors would indeed enjoy a free lunch. They would effectively be getting their hands on new shares for $1.60 against a market price of $2, while losing nothing on their existing holdings.

The other option you may have (but not always) is not to exercise the rights at all but to sell them. The value of your rights - in theory at least - is the difference between the expected market price of the stock after the rights issue and the exercise price of the rights.

The trade-off, of course, is that your percentage equity holding (or theoretical claim over the earnings) in the company will be "diluted" to the exent that other investors convert their rights to shares.

Placements

Rights issues can get a bit messy for everyone involved and they take a bit of organising. So some companies raise new equity - usually in relatively small amounts - by making a "placement" to an institution or small group of people.

Placements can sometimes disadvantage excluded shareholders by diluting their interests in the company's earnings.

For example, say you own 1000 out of a total of 10,000 issued shares in Marigold Hotels Limited. In other words, you own 10 per cent of the company and are theoretically entitled to 10 per cent of its earnings. If the company makes $1 million, you make $100,000 - although obviously it may not all be paid out to you as a dividend.

What if Marigold now decides to raise equity through a placement of 1000 shares at the current market price to a major institution. Suddenly, 11,000 shares are on issue and you still own 1000. Your holding has been diluted to 9.1 per cent of the company.

If the company makes the same $1 million profit, through no fault of your own your share of the profits has fallen from $100,000 to $90,909. The company's actions have literally "robbed" you of almost $10,000.

The key question is whether earnings will in fact remain at $1 million after the cash injection. If Marigold is raising capital to expand its proven, successful hotel chain into new markets, the equity placement may be just what it needs to take it to the next growth phase.

It could be that instead of a $1 million profit next year, the company's expansion is wildly successful and it makes $1.5 million, of which you have a claim on 9.1 per cent or $136,350. You're in the money again.

As with rights issues, all you can do is assess to what use the company is putting the new money. Then make a decision on whether you are better off in or out.

Share splits - half the price, double the fun?

You may wonder how it comes to be that so many companies still trade at less than $10. Surely, there should be plenty of big companies that have grown consistently for so long that their share prices should be at $50, $60, even $120.

In the US, you are more likely to come across shares trading at $50 or more. And if you could get your hands on an A-class share in Warren Buffet's Berkshire Hathaway Group, you would be handing over US$125,000 or thereabouts. So why the discrepancies?

The answer lies in a marketing device known as the share split. The theory, in extremis, goes that investors would rather buy 1000 shares at $2 each than 2 shares at $1000 each.

That being the case, every so often, companies that have watched their share prices rise over the months or years, may reset the price to half or even one-third of its former level (two-for-one, three-for-one splits and so on).

So what does a halving in price mean for your shares?

Bonus issues - a split with a difference

While some investors think of bonus issues as freebies from a company and the word "bonus" does imply something for nothing, the reality is that they have much the same effect as share splits.

Under a 1-for-4 bonus issue, shareholders receive one free share for every four shares they own. If you own 1000 shares in a stock currently trading at $2, you will receive 250 "free" shares.

Unfortunately, just as in a rights issue, the freebies increase the supply of shares and tend to drag the market price down.

1000 shares at the current market price - $2.00 $2000

250 "free" shares $0

Cost of all your shares $2000

The average value of your shares after the bonus issue will be the total cost of your shares ($2000) divided by the number of shares you now own (1250), which comes to $1.60. Your $2000 investment is still worth $2000 - only in theory you now have 1250 shares trading at $1.60 instead of 1000 shares trading at $2. Some freebie!

In reality, of course, bonus issues can work in your favour if they are made by quality companies and share prices don't retreat as far as theory would suggest.

But don't assume that you're guaranteed something for nothing. Just as the Reserve Bank can't print money without devaluing paper already in circulation, companies can't create value out of thin air.

Share buybacks: finally, a reward for shareholders

While some rights issues, bonus issues and share splits may be of more benefit to the company than they are to you, there's a relatively simple way a company can reward loyal shareholders - buy back its own shares.

This is the best way a company can create value for shareholders if it has ready funds and no immediate growth opportunities to pour them in to.

In much the same way as a bonus issue increases the number of shares in circulation and depresses their price, a buyback decreases the number of shares in circulation. This raises the earnings per share (same earnings, fewer shares, more to go around), which generally puts an upward influence on the share price.

If a company can halve its earnings per share by doubling its shares on issue, that same company can double its earnings per share simply by halving its number of shares.

Apart from its effect on earnings per share, a buyback is a sign that management is confident enough in the company's future to invest in itself. It also means that management does not necessarily feel obliged to expand for the sake of expansion, unless the right opportunities present themselves.

Coming up next in our educational series, we examine what to look for when it comes to share market information and how to use it.

The cyclical nature of market returns argues for evaluating manager performance over a full market cycle. When evaluating investment managers it is important to understand that managers can perform differently during various parts of the market cycle. Since a full market cycle incorporates a diverse range of environments, it provides a better context for performance evaluation.

While track records over entire market cycles may not be available for some managers, choosing a time frame which covers a wide range of market conditions provides the best context for fund manager performance evaluation.

Capital flight

Capital flight, in economics, occurs when assets or money rapidly flow out of a country, due to an event of economic consequence. Such events could be an increase in taxes on capital or capital holders or the government of the country defaulting on its debt that disturbs investors and causes them to lower their valuation of the assets in that country, or otherwise to lose confidence in its economic strength.

This leads to a disappearance of wealth, and is usually accompanied by a sharp drop in the exchange rate of the affected country—depreciation in a variable exchange rate regime, or a forced devaluation in a fixed exchange rate regime.

This fall is particularly damaging when the capital belongs to the people of the affected country, because not only are the citizens now burdened by the loss in the economy and devaluation of their currency, but probably also, their assets have lost much of their nominal value. This leads to dramatic decreases in the purchasing power of the country's assets and makes it increasingly expensive to import goods and acquire any form of foreign facilities, e.g. medical facilities.

Discussion

Legality

Capital flight may be legal or illegal under domestic law. Legal capital flight is recorded on the books of the entity or individual making the transfer, and earnings from interest, dividends, and realized capital gains normally return to the country of origin. Illegal capital flight, also known as illicit financial flows, is intended to disappear from any record in the country of origin and earnings on the stock of illegal capital flight outside of a country generally do not return to the country of origin. It is indicated as missing money from a nation's balance of payments.[1]

Within a country

Capital flight is also sometimes used to refer to the removal of wealth and assets from a city or region within a country. Post-apartheid South African cities are probably the most visible example of this phenomenon. The flight of capital from central cities to the suburbs that ring them was also common throughout the second half of the twentieth century in the United States.

Countries with resource-based economies experience the largest capital flight.[2] A classical view on capital flight is that it is currency speculation that drives significant cross-border movements of private funds, enough to affect financial markets.[3] The presence of capital flight indicates the need for policy reform.[4]

Examples

In 1995, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) estimated that capital flight amounted to roughly half of the outstanding foreign debt of the most heavily indebted countries of the world.

Capital flight was seen in some Asian and Latin American markets in the 1990s. Perhaps the most consequential of these was the 1997 Asian financial crisis that started in Thailand and spread though much of East Asia beginning in July 1997, raising fears of a worldwide economic meltdown due to financial contagion.

The Argentine economic crisis of 2001 was in part the result of massive capital flight, induced by fears that Argentina would default on its external debt (the situation was made worse by the fact that Argentina had an artificially low fixed exchange rate and was dependent on large levels of reserve currency). This was also seen in Venezuela in the early 1980s with one year's total export income leaving through illegal capital flight.

In the last quarter of the 20th century, capital flight was observed from countries that offer low or negative real interest rate (like Russia and Argentina) to countries that offer higher real interest rate (like the People's Republic of China).

A 2006 article in The Washington Post gave several examples of private capital leaving France in response to the country's wealth tax. The article also stated, "Eric Pinchet, author of a French tax guide, estimates the wealth tax earns the government about $2.6 billion a year but has cost the country more than $125 billion in capital flight since 1998."

A 2008 paper published by Global Financial Integrity estimated capital flight, also called illicit financial flows to be "out of developing countries are some $850 billion to $1 trillion a year."[7]

A 2009 article in The Times reported that hundreds of wealthy financiers and entrepreneurs had recently fled the United Kingdom in response to recent tax increases, and had relocated in low tax destinations such as Jersey, Guernsey, the Isle of Man, and the British Virgin Islands.

In May 2012 the scale of Greek capital flight in the wake of the first "undecided" legislative election was estimated at €4 billion a week[9] and later that month the Spanish Central Bank revealed €97 billion in capital flight from the Spanish economy for the first quarter of 2012.

In the book La Dette Odieuse de l'Afrique: Comment l'endettement et la fuite des capitaux ont saigné un continent (Amalion 2013), Léonce Ndikumana and James K. Boyce argue that more than 65% of Africa's borrowed debts do not even get into countries in Africa, but remain in private bank accounts in tax havens all over the world.

In the run up to the British Referendum on leaving the EU there was a net capital outflow of £77bn in the preceding two quarters, £65bn in the quarter immediately before the referendum and £59bn in March when the referendum campaign started. This corresponds to a figure of £2bn in the equivalent six months in the preceding year.

XO___XO XXX 10001 + 10 Global financial system

The global financial system is the worldwide framework of legal agreements, institutions, and both formal and informal economic actors that together facilitate international flows of financial capital for purposes of investment and trade financing. Since emerging in the late 19th century during the first modern wave of economic globalization, its evolution is marked by the establishment of central banks, multilateral treaties, and intergovernmental organizations aimed at improving the transparency, regulation, and effectiveness of international markets.[1][2]:74[3]:1 In the late 1800s, world migration and communication technology facilitated unprecedented growth in international trade and investment. At the onset of World War I, trade contracted as foreign exchange markets became paralyzed by money market liquidity. Countries sought to defend against external shocks with protectionist policies and trade virtually halted by 1933, worsening the effects of the global Great Depression until a series of reciprocal trade agreements slowly reduced tariffs worldwide. Efforts to revamp the international monetary system after World War II improved exchange rate stability, fostering record growth in global finance.

A series of currency devaluations and oil crises in the 1970s led most countries to float their currencies. The world economy became increasingly financially integrated in the 1980s and 1990s due to capital account liberalization and financial deregulation. A series of financial crises in Europe, Asia, and Latin America followed with contagious effects due to greater exposure to volatile capital flows. The global financial crisis, which originated in the United States in 2007, quickly propagated among other nations and is recognized as the catalyst for the worldwide Great Recession. A market adjustment to Greece's noncompliance with its monetary union in 2009 ignited a sovereign debt crisis among European nations known as the Eurozone crisis.

A country's decision to operate an open economy and globalize its financial capital carries monetary implications captured by the balance of payments. It also renders exposure to risks in international finance, such as political deterioration, regulatory changes, foreign exchange controls, and legal uncertainties for property rights and investments. Both individuals and groups may participate in the global financial system. Consumers and international businesses undertake consumption, production, and investment. Governments and intergovernmental bodies act as purveyors of international trade, economic development, and crisis management. Regulatory bodies establish financial regulations and legal procedures, while independent bodies facilitate industry supervision. Research institutes and other associations analyze data, publish reports and policy briefs, and host public discourse on global financial affairs.

While the global financial system is edging toward greater stability, governments must deal with differing regional or national needs. Some nations are trying to orderly discontinue unconventional monetary policies installed to cultivate recovery, while others are expanding their scope and scale. Emerging market policymakers face a challenge of precision as they must carefully institute sustainable macroeconomic policies during extraordinary market sensitivity without provoking investors to retreat their capital to stronger markets. Nations' inability to align interests and achieve international consensus on matters such as banking regulation has perpetuated the risk of future global financial catastrophes.

Implications of globalized capital

Balance of payments

The balance of payments accounts summarize payments made to or received from foreign countries. Receipts are considered credit transactions while payments are considered debit transactions. The balance of payments is a function of three components: transactions involving export or import of goods and services form the current account, transactions involving purchase or sale of financial assets form the financial account, and transactions involving unconventional transfers of wealth form the capital account.[47]:306–307 The current account summarizes three variables: the trade balance, net factor income from abroad, and net unilateral transfers. The financial account summarizes the value of exports versus imports of assets, and the capital account summarizes the value of asset transfers received net of transfers given. The capital account also includes the official reserve account, which summarizes central banks' purchases and sales of domestic currency, foreign exchange, gold, and SDRs for purposes of maintaining or utilizing bank reserves.

Because the balance of payments sums to zero, a current account surplus indicates a deficit in the asset accounts and vice versa. A current account surplus or deficit indicates the extent to which a country is relying on foreign capital to finance its consumption and investments, and whether it is living beyond its means. For example, assuming a capital account balance of zero (thus no asset transfers available for financing), a current account deficit of £1 billion implies a financial account surplus (or net asset exports) of £1 billion. A net exporter of financial assets is known as a borrower, exchanging future payments for current consumption. Further, a net export of financial assets indicates growth in a country's debt. From this perspective, the balance of payments links a nation's income to its spending by indicating the degree to which current account imbalances are financed with domestic or foreign financial capital, which illuminates how a nation's wealth is shaped over time.[18]:73[47]:308–313[48]:203 A healthy balance of payments position is important for economic growth. If countries experiencing a growth in demand have trouble sustaining a healthy balance of payments, demand can slow, leading to: unused or excess supply, discouraged foreign investment, and less attractive exports which can further reinforce a negative cycle that intensifies payments imbalances.[50]:21–22

A country's external wealth is measured by the value of its foreign assets net of its foreign liabilities. A current account surplus (and corresponding financial account deficit) indicates an increase in external wealth while a deficit indicates a decrease. Aside from current account indications of whether a country is a net buyer or net seller of assets, shifts in a nation's external wealth are influenced by capital gains and capital losses on foreign investments. Having positive external wealth means a country is a net lender (or creditor) in the world economy, while negative external wealth indicates a net borrower (or debtor).[48]:13,210

Unique financial risks

Nations and international businesses face an array of financial risks unique to foreign investment activity. Political risk is the potential for losses from a foreign country's political instability or otherwise unfavorable developments, which manifests in different forms. Transfer risk emphasizes uncertainties surrounding a country's capital controls and balance of payments. Operational risk characterizes concerns over a country's regulatory policies and their impact on normal business operations. Control risk is born from uncertainties surrounding property and decision rights in the local operation of foreign direct investments.[18]:422 Credit risk implies lenders may face an absent or unfavorable regulatory framework that affords little or no legal protection of foreign investments. For example, foreign governments may commit to a sovereign default or otherwise repudiate their debt obligations to international investors without any legal consequence or recourse. Governments may decide to expropriate or nationalize foreign-held assets or enact contrived policy changes following an investor's decision to acquire assets in the host country.[48]:14–17 Country risk encompasses both political risk and credit risk, and represents the potential for unanticipated developments in a host country to threaten its capacity for debt repayment and repatriation of gains from interest and dividends.[18]:425,526[51]:216

Participants

Economic actors

Each of the core economic functions, consumption, production, and investment, have become highly globalized in recent decades. While consumers increasingly import foreign goods or purchase domestic goods produced with foreign inputs, businesses continue to expand production internationally to meet an increasingly globalized consumption in the world economy. International financial integration among nations has afforded investors the opportunity to diversify their asset portfolios by investing abroad.[18]:4–5 Consumers, multinational corporations, individual and institutional investors, and financial intermediaries (such as banks) are the key economic actors within the global financial system. Central banks (such as the European Central Bank or the U.S. Federal Reserve System) undertake open market operations in their efforts to realize monetary policy goals.International financial institutions such as the Bretton Woods institutions, multilateral development banks and other development finance institutions provide emergency financing to countries in crisis, provide risk mitigation tools to prospective foreign investors, and assemble capital for development finance and poverty reduction initiatives.[24]:243 Trade organizations such as the World Trade Organization, Institute of International Finance, and the World Federation of Exchanges attempt to ease trade, facilitate trade disputes and address economic affairs, promote standards, and sponsor research and statistics publications.[52][53][54]

Regulatory bodies

Explicit goals of financial regulation include countries' pursuits of financial stability and the safeguarding of unsophisticated market players from fraudulent activity, while implicit goals include offering viable and competitive financial environments to world investors.[34]:57 A single nation with functioning governance, financial regulations, deposit insurance, emergency financing through discount windows, standard accounting practices, and established legal and disclosure procedures, can itself develop and grow a healthy domestic financial system. In a global context however, no central political authority exists which can extend these arrangements globally. Rather, governments have cooperated to establish a host of institutions and practices that have evolved over time and are referred to collectively as the international financial architecture.[14]:xviii[24]:2 Within this architecture, regulatory authorities such as national governments and intergovernmental organizations have the capacity to influence international financial markets. National governments may employ their finance ministries, treasuries, and regulatory agencies to impose tariffs and foreign capital controls or may use their central banks to execute a desired intervention in the open markets.[48]:17–21

Some degree of self-regulation occurs whereby banks and other financial institutions attempt to operate within guidelines set and published by multilateral organizations such as the International Monetary Fund or the Bank for International Settlements (particularly the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision and the Committee on the Global Financial System[55]).[27]:33–34 Further examples of international regulatory bodies are: the Financial Stability Board (FSB) established to coordinate information and activities among developed countries; the International Organization of Securities Commissions (IOSCO) which coordinates the regulation of financial securities; the International Association of Insurance Supervisors (IAIS) which promotes consistent insurance industry supervision; the Financial Action Task Force on Money Laundering which facilitates collaboration in battling money laundering and terrorism financing; and the International Accounting Standards Board (IASB) which publishes accounting and auditing standards. Public and private arrangements exist to assist and guide countries struggling with sovereign debt payments, such as the Paris Club and London Club.[24]:22[30]:10–11 National securities commissions and independent financial regulators maintain oversight of their industries' foreign exchange market activities.[19]:61–64 Two examples of supranational financial regulators in Europe are the European Banking Authority (EBA) which identifies systemic risks and institutional weaknesses and may overrule national regulators, and the European Shadow Financial Regulatory Committee (ESFRC) which reviews financial regulatory issues and publishes policy recommendations.[56][57]

Research organizations and other fora

Research and academic institutions, professional associations, and think-tanks aim to observe, model, understand, and publish recommendations to improve the transparency and effectiveness of the global financial system. For example, the independent non-partisan World Economic Forum facilitates the Global Agenda Council on the Global Financial System and Global Agenda Council on the International Monetary System, which report on systemic risks and assemble policy recommendations.[58][59] The Global Financial Markets Association facilitates discussion of global financial issues among members of various professional associations around the world.[60] The Group of Thirty (G30) formed in 1978 as a private, international group of consultants, researchers, and representatives committed to advancing understanding of international economics and global finance.

Future of the global financial system

The IMF has reported that the global financial system is on a path to improved financial stability, but faces a host of transitional challenges borne out by regional vulnerabilities and policy regimes. One challenge is managing the United States' disengagement from its accommodative monetary policy. Doing so in an elegant, orderly manner could be difficult as markets adjust to reflect investors' expectations of a new monetary regime with higher interest rates. Interest rates could rise too sharply if exacerbated by a structural decline in market liquidity from higher interest rates and greater volatility, or by structural deleveraging in short-term securities and in the shadow banking system (particularly the mortgage market and real estate investment trusts). Other central banks are contemplating ways to exit unconventional monetary policies employed in recent years. Some nations however, such as Japan, are attempting stimulus programs at larger scales to combat deflationary pressures. The Eurozone's nations implemented myriad national reforms aimed at strengthening the monetary union and alleviating stress on banks and governments. Yet some European nations such as Portugal, Italy, and Spain continue to struggle with heavily leveraged corporate sectors and fragmented financial markets in which investors face pricing inefficiency and difficulty identifying quality assets. Banks operating in such environments may need stronger provisions in place to withstand corresponding market adjustments and absorb potential losses. Emerging market economies face challenges to greater stability as bond markets indicate heightened sensitivity to monetary easing from external investors flooding into domestic markets, rendering exposure to potential capital flights brought on by heavy corporate leveraging in expansionary credit environments. Policymakers in these economies are tasked with transitioning to more sustainable and balanced financial sectors while still fostering market growth so as not to provoke investor withdrawal.[62]:xi-xiii

The global financial crisis and Great Recession prompted renewed discourse on the architecture of the global financial system. These events called to attention financial integration, inadequacies of global governance, and the emergent systemic risks of financial globalization.[63]:2–9 Since the establishment in 1945 of a formal international monetary system with the IMF empowered as its guardian, the world has undergone extensive changes politically and economically. This has fundamentally altered the paradigm in which international financial institutions operate, increasing the complexities of the IMF and World Bank's mandates.[30]:1–2 The lack of adherence to a formal monetary system has created a void of global constraints on national macroeconomic policies and a deficit of rule-based governance of financial activities.[64]:4 French economist and Executive Director of the World Economic Forum's Reinventing Bretton Woods Committee, Marc Uzan, has pointed out that some radical proposals such as a "global central bank or a world financial authority" have been deemed impractical, leading to further consideration of medium-term efforts to improve transparency and disclosure, strengthen emerging market financial climates, bolster prudential regulatory environments in advanced nations, and better moderate capital account liberalization and exchange rate regime selection in emerging markets. He has also drawn attention to calls for increased participation from the private sector in the management of financial crises and the augmenting of multilateral institutions' resources.

The Council on Foreign Relations' assessment of global finance notes that excessive institutions with overlapping directives and limited scopes of authority, coupled with difficulty aligning national interests with international reforms, are the two key weaknesses inhibiting global financial reform. Nations do not presently enjoy a comprehensive structure for macroeconomic policy coordination, and global savings imbalances have abounded before and after the global financial crisis to the extent that the United States' status as the steward of the world's reserve currency was called into question. Post-crisis efforts to pursue macroeconomic policies aimed at stabilizing foreign exchange markets have yet to be institutionalized. The lack of international consensus on how best to monitor and govern banking and investment activity threatens the world's ability to prevent future global financial crises. The slow and often delayed implementation of banking regulations that meet Basel III criteria means most of the standards will not take effect until 2019, rendering continued exposure of global finance to unregulated systemic risks. Despite Basel III and other efforts by the G20 to bolster the Financial Stability Board's capacity to facilitate cooperation and stabilizing regulatory changes, regulation exists predominantly at the national and regional levels.[65]

Reform efforts