Circular economy

A circular economy is a regenerative system in which resource input and waste, emission, and energy leakage are minimised by slowing, closing, and narrowing material and energy loops. This can be achieved through long-lasting design, maintenance, repair, reuse, remanufacturing, refurbishing, and recycling. This is in contrast to a linear economy which is a 'take, make, dispose' model of production .

Scope

The term encompasses more than the production and consumption of goods and services, including a shift from fossil fuels to the use of renewable energy, and the role of diversity as a characteristic of resilient and productive systems. It includes discussion of the role of money and finance as part of the wider debate, and some of its pioneers have called for a revamp of economic performance measurement tools.Origins

"The concept of a circular economy (CE) has been first raised by two British environmental economists David W. Pearce and R. Kerry Turner in 1989. In Economics of Natural Resources and the Environment, they pointed out that a traditional open-ended economy was developed with no built-in tendency to recycle, which was reflected by treating the environment as a waste reservoir".The circular economy is grounded in the study of feedback-rich (non-linear) systems, particularly living systems. A major outcome of this is the notion of optimising systems rather than components, or the notion of ‘design for fit’. As a generic notion it draws from a number of more specific approaches including cradle to cradle, biomimicry, industrial ecology, and the 'blue economy’.Moving away from the linear model

Linear "take, make, dispose" industrial processes and the lifestyles that feed on them deplete finite reserves to create products that end up in landfills or in incinerators.This realisation triggered the thought process of a few scientists and thinkers, including Walter R. Stahel, an architect, economist, and a founding father of industrial sustainability. Credited with having coined the expression "Cradle to Cradle" (in contrast with "Cradle to Grave", illustrating our "Resource to Waste" way of functioning), in the late 1970s, Stahel worked on developing a "closed loop" approach to production processes, co-founding the Product-Life Institute in Geneva more than 25 years ago. In the UK, Steve D. Parker researched waste as a resource in the UK agricultural sector in 1982, developing novel closed loop production systems mimicking, and integrated with, the symbiotic biological ecosystems they exploited.

Emergence of the idea

In their 1976 Hannah Reekman research report to the European Commission, "The Potential for Substituting Manpower for Energy", Walter Stahel and Genevieve Reday sketched the vision of an economy in loops (or circular economy) and its impact on job creation, economic competitiveness, resource savings, and waste prevention. The report was published in 1982 as the book Jobs for Tomorrow: The Potential for Substituting Manpower for Energy.Considered as one of the first pragmatic and credible sustainability think tanks, the main goals of Stahel's institute are product-life extension, long-life goods, reconditioning activities, and waste prevention. It also insists on the importance of selling services rather than products, an idea referred to as the "functional service economy" and sometimes put under the wider notion of "performance economy" which also advocates "more localisation of economic activity".

In broader terms, the circular approach is a framework that takes insights from living systems. It considers that our systems should work like organisms, processing nutrients that can be fed back into the cycle—whether biological or technical—hence the "closed loop" or "regenerative" terms usually associated with it.

The generic Circular Economy label can be applied to, and claimed by, several different schools of thought, that all gravitate around the same basic principles which they have refined in different ways. The idea itself, which is centred on taking insights from living systems, is hardly a new one and hence cannot be traced back to one precise date or author, yet its practical applications to modern economic systems and industrial processes have gained momentum since the late 1970s, giving birth to four prominent movements, detailed below. The idea of circular material flows as a model for the economy was presented in 1966 by Kenneth E. Boulding in his paper, The Economics of the Coming Spaceship Earth. Promoting a circular economy was identified as national policy in China’s 11th five-year plan starting in 2006. The Ellen MacArthur Foundation, an independent charity established in 2010, has more recently outlined the economic opportunity of a circular economy. As part of its educational mission, the Foundation has worked to bring together complementary schools of thought and create a coherent framework, thus giving the concept a wide exposure and appeal.

Most frequently described as a framework for thinking, its supporters claim it is a coherent model that has value as part of a response to the end of the era of cheap oil and materials and can contribute to the transition to a low carbon economy. In line with this, a circular economy can contribute to meet the COP 21 Paris Agreement. The emissions reduction commitments made by 195 countries at the COP 21 Paris Agreement, are not sufficient to limit global warming to 1.5 °C. To reach the 1.5 °C ambition it is estimated that additional emissions reductions of 15 billion tonnes CO2 per year need to be achieved by 2030. Circle Economy and Ecofys estimated that circular economy strategies may deliver emissions reductions that could basically bridge the gap by half.

Sustainability

The circular economy seems intuitively to be more sustainable than the current linear economic system. The reduction of resource inputs into and waste and emission leakage out of the system reduces resource depletion and environmental pollution. However, these simple assumptions are not sufficient to deal with the involved systemic complexity and disregards potential trade-offs. For example, the social dimension of sustainability seems to be only marginally addressed in many publications on the Circular Economy, and there are cases that require different or additional strategies, like purchasing new, more energy efficient equipment. By reviewing the literature, a team of researchers from Cambridge and TU Delft could show that there are at least eight different relationship types between sustainability and the circular economy:[1]1. Conditional relation

2. Strong conditional relation

3. Necessary but not sufficient conditional relation

4. Beneficial relationship

5. Subset relation (structured and unstructured)

6. Degree relation

7. Cost-benefit/trade-off relation

8. Selective relation

Key elements

With a surge in popularity, many circular principles are available, varying widely depending on the problems being addressed, the audience, or the lens through which the author views the world. There are at least the following key elements to be identified within a circular economy.Prioritise regenerative resources

Ensure renewable, reusable, non-toxic resources are utilised as materials and energy in an efficient way. Ultimately the system should aim to run on ‘current sunshine’ and generate energy through renewable sources. An example of this principle is The Biosphere Rules framework for closed-loop production which identifies Power Autonomy as one of nature's principles for sustainable manufacturing. It requires that energy efficiency be first maximized so that renewable energy becomes economical. It also requires that materials need to be non-toxic to be able to recirculate without causing harm to the living environment.Use waste as a resource

The second element aims to utilise waste streams as a source of secondary resources and recover waste for reuse and recycling and is grounded on the idea that waste does not exist. It is necessary here to design out waste, meaning that both the biological and technical components (nutrients) of a product are designed intentionally in such a way that waste streams are minimalized.Design for the future

Account for the systems perspective during the design process, to use the right materials, to design for appropriate lifetime and to design for extended future use. Meaning that a product is designed to fit within a materials cycle, can easily be dissembled and can easily be used with a different purpose. Hereby one could consider strategies like emotionally durable design. It should be stressed that there is not something like one ideal blueprint for future design. Modularity, versatility and adaptiveness are to be prioritised in an uncertain and fast evolving world, meaning that diverse products, materials, and systems, with many connections and scales are more resilient in the face of external shocks, than monotone systems built simply for efficiency.Preserve and extend what’s already made

While resources are in-use, maintain, repair and upgrade them to maximise their lifetime and give them a second life through take back strategies when applicable. This could mean that a product is accompanied with a pre-thought maintenance programme to maximise its lifetime, including a buyback program and supporting logistics system. Second hand sales or refurbish programs also falls within this element.Collaborate to create joint value

Within a circular economy, one should work together throughout the supply chain, internally within organisations and with the public sector to increase transparency and create joint value. For the business sector this calls for collaboration within the supply chain and cross-sectoral, recognising the interdependence between the different market players. Governments can support this by creating the right incentives, for example via common standards within a regulatory framework and provide business support.Incorporate digital technology

Track and optimise resource use and strengthen connections between supply chain actors through digital, online platforms and technologies that provide insights. It also encompasses virtualized value creation and delivering, for example via 3D printers, and communicating with customers virtually.Prices or other feedback mechanisms should reflect real costs

In a circular economy, prices act as messages, and therefore need to reflect full costs in order to be effective. The full costs of negative externalities are revealed and taken into account, and perverse subsidies are removed. A lack of transparency on externalities acts as a barrier to the transition to a circular economy.The circular economy framework

The circular economy is a highly contested framework, as evidenced by a recent review of 114 circular economy understandings . Nevertheless, several core principles can be identified across the different frameworks. These are depicted below.Systems thinking

The ability to understand how things influence one another within a whole. Elements are considered as ‘fitting in’ their infrastructure, environment and social context. Whilst a machine is also a system, systems thinking usually refers to nonlinear systems: systems where through feedback and imprecise starting conditions the outcome is not necessarily proportional to the input and where evolution of the system is possible: the system can display emergent properties. Examples of these systems are all living systems and any open system such as meteorological systems or ocean currents, even the orbits of the planets have nonlinear characteristics.Understanding a system is crucial when trying to decide and plan (corrections) in a system. Missing or misinterpreting the trends, flows, functions of, and human influences on, our socio-ecological systems can result in disastrous results. In order to prevent errors in planning or design an understanding of the system should be applied to the whole and to the details of the plan or design. The Natural Step created a set of systems conditions (or sustainability principles) that can be applied when designing for (parts of) a circular economy to ensure alignment with functions of the socio-ecological system.

The concept of the circular economy has previously been expressed as the circulation of money versus goods, services, access rights, valuable documents, etc., in macroeconomics. This situation has been illustrated in many diagrams for money and goods circulation associated with social systems. As a system, various agencies or entities are connected by paths through which the various goods etc., pass in exchange for money. However, this situation is different from the circular economy described above, where the flow is unilinear - in only one direction, that is, until the recycled goods again are spread over the world.

Biomimicry

Janine Benyus, author of "Biomimicry: Innovation Inspired by Nature", defines her approach as "a new discipline that studies nature's best ideas and then imitates these designs and processes to solve human problems. Studying a leaf to invent a better solar cell is an example. I think of it as "innovation inspired by nature. Biomimicry relies on three key principles:- Nature as model: Biomimicry studies nature’s models and emulates these forms, processes, systems, and strategies to solve human problems.

- Nature as measure: Biomimicry uses an ecological standard to judge the sustainability of our innovations.

- Nature as mentor: Biomimicry is a way of viewing and valuing nature. It introduces an era based not on what we can extract from the natural world, but what we can learn from it.

Industrial ecology

Industrial Ecology is the study of material and energy flows through industrial systems. Focusing on connections between operators within the "industrial ecosystem", this approach aims at creating closed loop processes in which waste is seen as input, thus eliminating the notion of undesirable by-product. Industrial ecology adopts a systemic - or holistic - point of view, designing production processes according to local ecological constraints whilst looking at their global impact from the outset, and attempting to shape them so they perform as close to living systems as possible. This framework is sometimes referred to as the "science of sustainability", given its interdisciplinary nature, and its principles can also be applied in the services sector. With an emphasis on natural capital restoration, Industrial Ecology also focuses on social wellbeing.Cradle to cradle

Created by Walter R. Stahel, a Swiss architect who graduated from the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology Zürich in 1971. He has been influential in developing the field of sustainability by advocating philosophies of 'service-life extension of goods - reuse, repair, remanufacture, upgrade technologically' as they apply to industrialised economies. He co-founded the Product Life Institute in Geneva, Switzerland, a consultancy devoted to developing sustainable strategies and policies, after receiving recognition for his prize winning paper 'The Product Life Factor' in 1982. His ideas and those of similar theorists led to what is now known as the circular economy, in which industry adopts the reuse and service-life extension of goods as a strategy of waste prevention, regional job creation, and resource efficiency in order to decouple wealth from resource consumption, in other words, to dematerialise the industrial economy.Cooper (2005) proposed a theoretical model that illustrates the significance of product life spans in progressing towards sustainable consumption. According to the model, longer product life spans can contribute to eco-efficiency and sufficiency and thus slow consumption and help societies progress towards sustainable consumption.

Blue economy

Initiated by former Ecover CEO and Belgian entrepreneur Gunter Pauli, derived from the study of natural biological production processes the official manifesto states, "using the resources available...the waste of one product becomes the input to create a new cash flow". Based on 21 founding principles, the Blue Economy insists on solutions being determined by their local environment and physical / ecological characteristics, putting the emphasis on gravity as the primary source of energy - a point that differentiates this school of thought from the others within the Circular Economy. The report - which doubles as the movement’s manifesto - describes "100 innovations which can create 100 million jobs within the next 10 years", and provides many example of winning South-South collaborative projects, another original feature of this approach intent on promoting its hands-on focus."The Biosphere Rules"

The Biosphere Rules is a framework for implementing closed loop production processes. They derived from nature systems and translated for industrial production systems. The five principles are Materials Parsimony, Value Cycling, Power Autonomy, Sustainable Product Platforms and Function Over Form.Towards the circular economy

In January 2012, a report was released entitled Towards the Circular Economy: Economic and business rationale for an accelerated transition. The report, commissioned by the Ellen MacArthur Foundation and developed by McKinsey & Company, was the first of its kind to consider the economic and business opportunity for the transition to a restorative, circular model. Using product case studies and economy-wide analysis, the report details the potential for significant benefits across the EU. It argues that a subset of the EU manufacturing sector could realise net materials cost savings worth up to $630 billion annually towards 2025—stimulating economic activity in the areas of product development, remanufacturing and refurbishment. Towards the Circular Economy also identified the key building blocks in making the transition to a circular economy, namely in skills in circular design and production, new business models, skills in building cascades and reverse cycles, and cross-cycle/cross-sector collaboration.In January 2015 a Definitive Guide to The Circular Economy was published by Coara with the specific aim to raise awareness amongst the general population of the environmental problems already being caused by our "throwaway culture". Waste Electrical and Electronic Equipment (WEEE), in particular, is contributing to excessive use of landfill sites across the globe in which society is both discarding valuable metals but also dumping toxic compounds that are polluting the surrounding land and water supplies. Mobile devices and computer hard drives typically contain valuable metals such as silver and copper but also hazardous chemicals such as lead, mercury and cadmium. Consumers are unaware of the environmental significance of upgrading their mobile phones, for instance, on such a frequent basis but could do much to encourage manufacturers to start to move away from the wasteful, polluting linear economy towards are sustainable circular economy.

Impact in Europe

On 17 December 2012, the European Commission published a document entitled Manifesto for a Resource Efficient Europe. This manifesto clearly stated that "In a world with growing pressures on resources and the environment, the EU has no choice but to go for the transition to a resource-efficient and ultimately regenerative circular economy." Furthermore, the document highlighted the importance of "a systemic change in the use and recovery of resources in the economy" in ensuring future jobs and competitiveness, and outlined potential pathways to a circular economy, in innovation and investment, regulation, tackling harmful subsidies, increasing opportunities for new business models, and setting clear targets.The European environmental research and innovation policy aims at supporting the transition to a circular economy in Europe, defining and driving the implementation of a transformative agenda to green the economy and the society as a whole, to achieve a truly sustainable development. Research and innovation in Europe are financially supported by the programme Horizon 2020, which is also open to participation worldwide.

The European Commission introduced a Circular Economy proposal in 2015. Historically, the policy debate in Brussels mainly focused on waste management which is the second half of the cycle, and very little is said about the first half: eco-design. To draw the attention of policymakers and other stakeholders to this loophole, the Ecothis, an EU campaign was launched raising awareness about the economic and environmental consequences of not including eco-design as part of the circular economy package.

Circular business model

A circular economy calls upon opportunities to create greater value and align incentives through business models that build on the interaction between products and services. Linder and Williander describe a circular business model as “a business model in which the conceptual logic for value creation is based on utilizing the economic value retained in products after use in the production of new offerings”.Basically this means that a circular business model is not focused merely on selling a product, but encompasses a shift in thinking about value proposition, bringing forward a whole range of different business models to be used. To mention just a few examples: product-service systems, virtualized services, and collaborative consumption which encompasses the sharing economy. This comprises both the incentives and benefits offered to customers for bringing back used products and a change in revenue streams, comprising payments for a circular product or service, or payments for delivered availability, usage, or performance related to the product-based service offered.

These new ways of doing business require businesses to create an attractive business model for financiers, and financiers to change the way they perceive the risks and opportunities associated with these models. To help businesses position themselves in a circular context and develop future strategies for doing business in a circular economy, the Value Hill has been created. The Value Hill proposes a categorisation based on the lifecycle phases of a product: pre-, in- and post- use. This allows businesses to position themselves on the Value Hill and understand possible circular strategies they can implement as well as identify missing partners in their circular network. The Value Hill provides an overview of the circular partners and collaborations essential to the success of a circular value network.

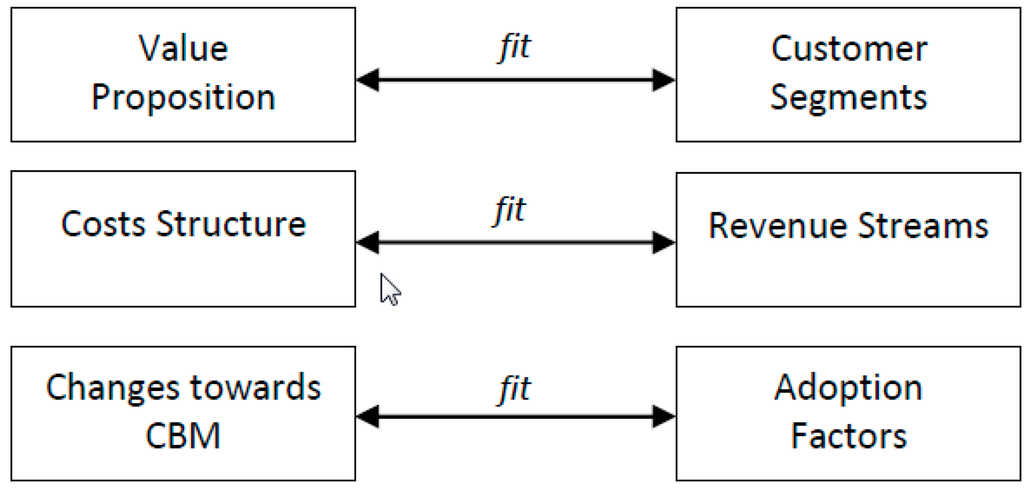

Mateusz Lewandowski provides a proposition to address this need to design circular business models and presents an extension of the framework from Osterwalder and Pigneur, namely the circular business model canvas (CBMC). The CBMC consists of eleven building blocks, encompassing not only traditional components with minor modifications, but also material loops and adaptation factors. Those building blocks allow the designing of a business model according to the principles of circular economy.

XXX . V Designing the Business Models for Circular Economy—Towards the Conceptual Framework

Switching from the current linear model of economy to a circular one has recently attracted increased attention from major global companies e.g., Google, Unilever, Renault, and policymakers attending the World Economic Forum. The reasons for this are the huge financial, social and environmental benefits. However, the global shift from one model of economy to another also concerns smaller companies on a micro-level. Thus, comprehensive knowledge on designing circular business models is needed to stimulate and foster implementation of the circular economy. Existing business models for the circular economy have limited transferability and there is no comprehensive framework supporting every kind of company in designing a circular business model. This study employs a literature review to identify and classify the circular economy characteristics according to a business model structure. The investigation in the eight sub-domains of research on circular business models was used to redefine the components of the business model canvas in the context of the circular economy. Two new components—the take-back system and adoption factors—have been identified, thereby leading to the conceptualization of an extended framework for the circular business model canvas. Additionally, the triple fit challenge has been recognized as an enabler of the transition towards a circular business model. Some directions for further research have been outlined, as well.

1. Introduction

Switching from the current linear model of economy to a circular one would not only bring savings of hundreds of billions US dollars to the EU alone, but also significantly reduce the negative impact on the natural environment [1,2]. This is why the circular economy (CE) has attracted increased attention as one of the most powerful and most recent moves towards sustainability [3,4]. The transition to the circular economy entails four fundamental building blocks—materials and product design, new business models, global reverse networks, and enabling conditions [5]. Switching an economy to a circular one depends, on the one hand, on policymakers and their decisions [6]; on the other hand, it depends on introducing circularity into their business models by business entities [7]. The scope of interest of this study is limited to the latter, micro-level perspective of designing circular business models.

Comprehensive knowledge on designing circular business models is needed to stimulate and foster implementation of the circular economy on a micro-level. Existing knowledge provides several well-elaborated and verified frameworks of business models, design patterns and tools to build a business model [8,9]. Although many case studies revealed several types of circular business actions or models [4,7], these models have limited transferability. There are very few studies covering, in a more comprehensive manner, how a circular business model framework should look. Previous research instead has taken the following approaches: building on a business model canvas (BMC) and classifying the product-service system characteristics according to its structure [10]; significantly reconstructing the BMC into a business cycle canvas to support practitioners in thinking in business systems and beyond the individual business model [11]; using it as a part of a bigger framework of a business model limited to eco-innovation [12]; or extending it to encompass wider social perspectives of costs and benefits [13]. Other studies provide some steps for analyzing an existing business model for potential opportunities to introduce circularity [7,14].

None of these reviewed studies have provided satisfactory answers to the following questions: How may the principles of the circular economy be applied to a business model? What components should a circular business model consist of to be applicable to every company? This study considers the circular economy as a new contribution to the development of business model theory. Because changing a company’s business model into a circular one is challenging, the following research provides a conceptual framework of the circular business model to support practitioners in the transition process from linear business models to more circular ones.

The paper is structured as follows. Section 2 presents the concept of this study and methodological remarks. Section 3 identifies the specificity of circular business models according to the eight sub-domains of research in the area of business models proposed by Pateli and Giaglis [15]. Section 4 classifies the findings of the review according to the business model framework developed by Osterwalder and Pigneur [8]. Thus, the nine building blocks of a business model framework are characterized in the context of the circular economy. This section reveals the need to extend the business model framework to make it more applicable to the circular economy. Section 5 provides a proposition to address this need and presents a conceptualization of an extended framework of business model—the circular business model canvas (CBMC). Section 6 provides suggestions for future research. Section 7 presents the conclusions of the study.

2. The Method and Concept of the Study

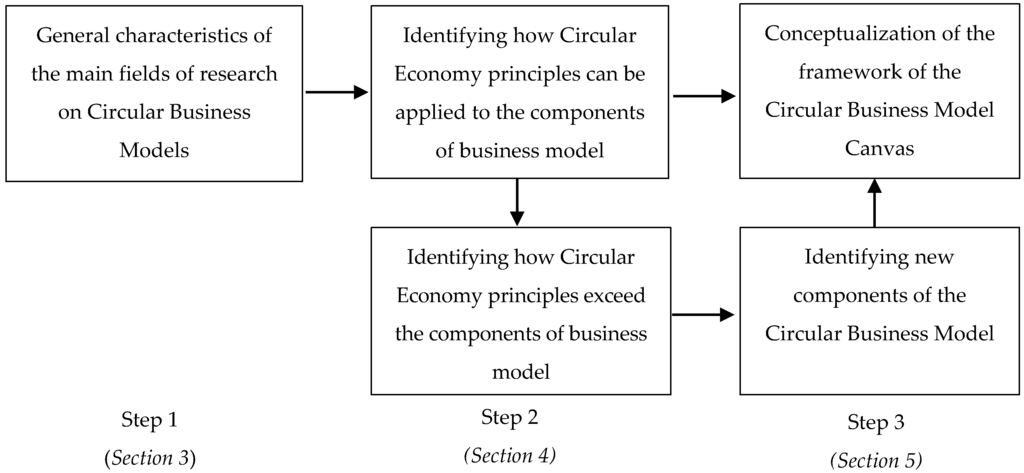

In order to answer the questions how the principles of the circular economy can be applied to a business model, and which universally applicable components are needed for a circular business model, a narrative conceptual review has been employed.The process was divided into three steps.

- (1)

- Identification of the state of the art on business models in the CE (circular business models)

- (2)

- Categorization of the initial body of literature according to the components of business model structure

- (3)

- Synthesis and development of the framework for a circular business model

2.1. Literature Review—Conceptual Frameworks for Categorizing the Research on Circular Business Models

This step identified the body of knowledge needed to obtain the answers for the research questions in the next steps. The following academic databases were used for the literature search: EBSCO Host, Google Scholar, Scopus, and ProQuest. Key words included variations on terms such as circular economy, business model, circular business model, sustainable business model. Then a complementary manual search was conducted on the websites of contributors to circular economy to look for other relevant papers, reports and books. Also the anonymous reviewers suggested some additional references.This literature search generated articles on conceptualizing the state of the art on business models in the circular economy (circular business models) according to the eight sub-domains of research in the area of business models proposed by Pateli and Giaglis [15]. Those sub-domains include: definitions, components, taxonomies, conceptual models, design methods and tools, adoption factors, evaluation models, and change methodologies [15]. The research in the sub-domain of definitions concerns defining the purpose, scope, and primary elements of a business model, as well as exploring its relationships with other business concepts, such as strategy and business processes. Thus, in relation to circular business models, a wider context of the circular economy must be explained in the first place. Research on components of business models focuses on identifying its fundamental constructs and constituent elements. They are derived from the main principles of CE. Research in the taxonomies’ sub-domain provides possible categorizations of circular business models into a number of typologies based on various criteria. Investigations related to the conceptual models focus on identifying and describing the relationship between the constituent elements of a circular business model, and include their graphical representation. Exploration of the design methods and tools concerns the development and use of methods, languages, standards and software to allow organizations to design, experiment, and change business models in an easy and cost-effective way into more circular business models. The research related to the adoption factors focuses on the factors that affect this change, as well as on socioeconomic implications of circular business models. The sub-domain related to evaluation models focuses on identifying criteria for assessing the feasibility, viability, and profitability of circular business models or evaluating them against alternative or best practice cases. Investigation concerning change methodologies pertain to guidelines, steps, and actions to be taken for transforming existing business models into a more circular one. Table 1 below presents an overview of this step, and the results are presented in the Section 2. This step identified the body of knowledge needed to obtain the answers for the research questions in the next steps.

| CBM Research Domains | Authors |

|---|---|

| Definitions | EMF Vol. 1&2 [2,4]; Joustra et al. [16]; Mentink [11]; Scott [3]; Lovins et al. [17]; Renswoude et al. [7]; Linder & Williander [18]; Ayres & Simonis [19]; Renner [20] |

| Components | EMF Vol. 1. [4]; Renswoude et al. [7]; Boons and Lüdeke-Freund [21]; Laubscher and Marinelli [22]; EMF [23]; Mentink [11]; Govindan, Soleimani, & Kannan [24] |

| Taxonomies | Lacy et al. [25]; Bakker et al. [26]; Damen [27]; EMF Vol. 1. [4]; Lacy et al. [28]; WRAP [29]; Renswoude et al. [7]; Planing [5]; Jong et al. [14]; Tukker and Tischner [30]; Van Ostaeyen et al. [31]; El-Haggar [32]; Bakker et al. [33]; Ludeke-Freund [12]; Moser and Jakl [34]; Mentink [11]; Scott [3]; Bautista-Lazo [35]; Tukker [36]; EMF [6] |

| Conceptual Models | Mentink [11]; Wirtz [9]; Osterwalder and Pigneur [8]; Barquet et al. [10]; Osterwalder et al. [37]; Ludeke-Freund [12]; Dewulf [13]; Stubbs & Cocklin [38]; Roome and Louche [39]; Gauthier and Gilomen [40]; Abdelkafi and Tauscher [41]; Jabłoński [42]; Upward and Jones [43]; Nilsson & Söderberg [44] |

| Design Methods and Tools | Joustra et al. [16]; Jong et al. [14]; Scott [3]; Renswoude et al. [7]; Osterwalder and Pigneur [8]; Mentink [11]; Barquet et al. [10]; Jabłoński [42]; Parlikad et al. [45]; El-Haggar [32]; Guinée [46] |

| Adoption Factors | Winter [47]; Planing [5]; Lacy et al. [28]; Joustra et al. [16]; Scott [3]; Parlikad et al. [45]; Mentink [11]; Laubscher and Marinelli [22]; EMF Vol. 1. [4]; Renswoude et al. [7]; Scheepens et al. [48]; EMF [6]; Jong et al. [14]; Beuren et al. [49]; Jabłoński [50]; Pearce [51]; Linder & Williander [18]; Parlikad, et al. [45]; Beuren et al. [49]; Jabłoński (2015); Zairul et al. [52]; Roos [53]; Bechtel et al. [54]; UNEP [55]; Besch [56]; Heese et al. [57]; Walsh [58]; Firnkorn & Muller [59]; Shafiee & Stec [60] |

| Evaluation Models | Winter [47]; Laubscher and Marinelli [22]; Mentink [11]; EMF [23]; Andersson & Stavileci [61]; Jasch [62]; Jasch [63]; Gale [64] |

| Change Methodologies | Scott [3]; Roome & Louche [39]; Gauthier & Gilomen [40] |

2.2. Categorization of the Initial Body of Literature According to the Components of Business Model Structure

The second step identified how the idea of circular economy can be applied to each component of the business model. This approach was inspired by Barquet et al. [10], who used a similar one for the characteristics of product-service systems (PSS). Business model structure was defined on the basis of the business model canvas (BMC) developed by Osterwalder and Pigneur [8]. BMC was chosen due to the ease of its practical application, complexity of components, worldwide recognition, and previous contributions to the development of circular business models [10,11,12]. However, a relatively large proportion of the literature pointed out several ways of applying the principles of the circular economy which exceeded the existing components of the business model. Table 2 below presents an overview of this step, and the results are presented in Section 3.

Table 2. Example categorization of the literature devoted to the circular economy according to a business model structure.

| BM components | Authors |

|---|---|

| Partners | Scott [3]; Joustra et al. [16]; El-Haggar [32]; Renswoude et al. [7]; Sheu [65]; Robinson et al. [66]; EMF Vol. 1. [4] |

| Key Activities | El-Haggar [32]; Scott [3]; WRAP [29]; Renswoude et al. [7]; Lacy et al. [28]; Rifkin [67]; Lacy et al. [25]; Joustra et al. [16]; EMF Vol. 3 [1]; Laubscher and Marinelli [22]; EMF Vol. 1. [4]; EMF [23]; EMF [6] |

| Key Resources | Planing [5]; Renswoude et al. [7]; Lacy et al. [28]; El-Haggar [32]; EMF [23]; Freyermuth [68]; Scott [3] |

| Value Proposition and Customer Segments | Jong et al. [14]; Planing [5]; Renswoude et al. [7]; Lacy et al. [28]; Parlikad et al. [45]; Bakker et al. [33]; El-Haggar [32]; Lacy et al. [25]; Scott [3]; EMF Vol. 1. [4]; Tukker and Tischner [30]; Tukker [36]; Laubscher and Marinelli [22]; Bakker et al. [26]; EMF [6] |

| Customer Relations | Renswoude et al. [7]; Recycling 2.0 [69]; Lacy et al. [25] |

| Channels | EMF [6]; Recycling 2.0 [69]; EMF [23] |

| Cost Structure | Laubscher and Marinelli [22]; Mentink [11]; Subramanian and Gunasekaran [70]; Sivertsson and Tell [71]; Berning and Venter [72]; Barquet et al. [10] |

| Revenue Streams | Van Ostaeyen et al. [31]; Renswoude et al. [7]; Tukker [36] |

| Additional Issues Related to Circular Economy | Material loops: EMF Vol. 1&2 [2,4]; Mentink [11]; Renswoude et al. [7]; Lacy et al. [28]; WRAP [29]; EMF Vol. 3 [1]; Govindan et al. [24]; El-Haggar [32]; EMF [23]; Freyermuth [68]; Scott [3]; Lacy et al. [25]; Planing [5]; |

| Adoption factors: Planing [5]; Scott [3]; El-Haggar [32]; Laubscher and Marinelli [22]; Lacy et al. [28]; Joustra et al. [16]; Jong et al. [14]; Renswoude et al. [7]; Barquet et al. [10]; Mentink [11]; Guinée [46]; EMF [23]; EMF [4]; EMF [6]; Parlikad et al. [45]; Stubbs & Cocklin [38]; Skelton and Pattis [73]; Winter [47] |

2.3. Synthesis and Development of the Framework of Circular Business Model

Pursuing better answers to the research questions resulted in undertaking step 3. This step synthesizes how the circular economy principles apply to each component of the business model, and proposes the new components of the circular business model. These components pertain to the ways in which the CE principles exceeded the popular business model framework. Additionally, advantages and disadvantages of the new framework were outlined. These results are presented in the Section 4.3. Research on Circular Business Models—The Review

3.1. Definitions

Although it is a contemporary movement, the circular economy is based on old ideas [74]; it is thus reasonable to outline its specificity. This includes the definitions, the origins of the movement, and its main principles. CE was probably first defined and conceptualized in the Ellen MacArthur Foundations report, as “an industrial system that is restorative or regenerative by intention and design” [4]. This means pursuing and creating the opportunities for a shift from an “end-of-life” concept to Cradle-to-Cradle™, from using unrenewable energy towards using renewable, from using toxic chemicals to their elimination, from much waste to eliminating waste through the superior design of materials, products, systems, and also business models [4]. The circular economy becomes a new vision of the treatment of resources, energy, value creation and entrepreneurship [16].Linder and Williander [18] define a circular business model as “a business model in which the conceptual logic for value creation is based on utilizing the economic value retained in products after use in the production of new offerings” (p. 2). Mentink [11] defines CE as “an economic system with closed material loops,” and a circular business model as “the rationale of how an organization creates, delivers and captures value with and within closed material loops” (p. 35). He argues that circular business models do not necessarily aim to balance ecological, social and ecological needs, in contrast to business models, although at the same time they can serve sustainability goals [11]. However, another approach is also supported in the literature. Most recently, Scott [3] provided a useful conceptualization of CE in relation to sustainability. He argues for understanding the circular economy as “a concept used to describe a zero-waste industrial economy that profits from two types of material inputs: (1) biological materials are those that can be reintroduced back into the biosphere in a restorative manner without harm or waste (i.e: they breakdown naturally); and, (2) technical materials, which can be continuously re-used without harm or waste” (p. 6). In turn, he defines sustainability as the capacity to continue into the long term and, at the same time, as a mechanism that enables the circular economy to work [3].

The general concept underlying the circular economy has been developed by many schools of thought, such as Regenerative Design, Performance Economy, Cradle to Cradle, Industrial Ecology, Biomimicry, Blue Economy, Permaculture, Natural Capitalism, Industrial Metabolism and Industrial Symbiosis [2,4,17,19,20]. Those schools of thought are complementary to each other and provided the foundation for the main principles of this new approach to economy [2,4,7,16]:

- (1)

- Design out waste/Design for reuse

- (2)

- Build resilience through diversity

- (3)

- Rely on energy from renewable sources

- (4)

- Think in systems

- (5)

- Waste is food/Think in cascades/Share values (symbiosis)

This variety of concepts supports Scott’s [3] approach to the relation between sustainability and circular economy.

3.2. Components

The fundamental constructs and constituent elements of circular business models can be derived from the main principles of the circular economy. In the literature, such components are understood and defined variously, for instance: the ReSOLVE (regenerate, share, optimize, loop, virtualize, exchange) framework [4,23], ways of circular value creation [7], normative requirements for business models [21], and areas for integration [22].There are six business actions to implement the principles of the circular economy and which represent major circular business opportunities depicted by the ReSOLVE framework [23]. Regenerate signifies the shift to renewable energy and materials. It is related to returning recovered biological resources to the biosphere. Thus it aims to reclaim, retain, and regenerate the health of ecosystems. Share actions aim at maximizing utilization of products by sharing them among users. It may be realized through peer-to-peer sharing of private products or public sharing of a pool of products. Sharing means also reusing products as long as they are technically acceptable to use (e.g., second-hand), and prolonging their life through maintenance, repair, and design-enhancing durability. Optimise actions are focused on increasing the performance/efficiency of a product and removing waste in the production process and in the supply chain. They may also be related to leveraging big data, automation, remote sensing, and steering. What is important is that optimization does not require changing the product or the technology. Loop actions aim at keeping components and materials in closed loops. The higher priority is given to inner loops. Virtualize actions assume to deliver particular utility virtually instead of materially. Exchange actions are focused on replacing old materials with advanced non-renewable materials and/or with applying new technologies (e.g., 3D printing). It may also be related to choosing new products and services [23].

Renswoude et al. [7] identify similar ways of circular value creation, pertaining to the short cycle, where products and services are maintained, repaired and adjusted, to the long cycle which extends the lifetime of existing products and processes, to cascades based on creating new combinations of resources and material components and purchasing upcycled waste streams, to pure circles in which resources and materials are 100% reused, to dematerialized services offered instead of physical products and to production on demand.

Other studies identified four normative requirements for business models for sustainable innovation, grounded in wider concepts such as sustainable development [21]. The first is a value proposition reflecting the balance of economic, ecological and social needs. The second is a supply chain engaging suppliers into sustainable supply chain management (materials cycles). The third is a customer interface, motivating customers to take responsibility for their consumption. The fourth is a financial model, mainly reflecting an appropriate distribution of economic costs and benefits among actors involved in the business model [21]. Boons and Lüdeke-Freund [21] (p. 13) also noticed that comparable conceptual notions of sustainable business models did not exist.

Mentink [11] (p. 34) used a similar approach to the business model as Frankenberger et al. [75], and outlined the changes of business model components needed for developing a more circular service model, such as:

- value propositions (what?)—products should become fully reused or recycled, which requires reverse logistics systems, or firms should turn towards product-service system (PSS) and sell performance related to serviced products

- activities, processes, resources and capabilities (how?)—products have to be made in specific processes, with recycled materials and specific resources, which may require not only specific capabilities but also creating reverse logistics systems and maintaining relationships with other companies and customers to assure closing of material loops

- revenue models (why?)—selling product-based services charged according to their use

- customers or customer interfaces (who?)—selling “circular” products or services may require prior changes of customer habits or, if this is not possible, even changes of customers

Laubscher and Marinelli [22] identified six key areas for integration of the circular economy principles with the business model:

- (1)

- Sales model—a shift from selling volumes of products towards selling services and retrieving products after first life from customers

- (2)

- Product design/material composition—the change concerns the way products are designed and engineered to maximize high quality reuse of product, its components and materials

- (3)

- IT/data management—in order to enable resource optimization a key competence is required, which is the ability to keep track of products, components and material data

- (4)

- Supply loops—turning towards the maximization of the recovery of own assets where profitable and to maximization of the use of recycled materials/used components in order to gain additional value from product, component and material flows

- (5)

- Strategic sourcing for own operations—building trusted partnerships and long-term relationships with suppliers and customers, including co-creation

- (6)

- HR/incentives—a shift needs adequate culture adaptation and development of capabilities, enhanced by training programs and rewards

One of the most important components of circular business models is the reversed supply-chain logistics. A comprehensive review on this subject has been done by Govindan, Soleimani, and Kannan [24].

3.3. Taxonomies

In the literature, there are several propositions of how to categorize business models. Most of them are very similar and use the criterion of the source of value creation (e.g., [4,7,25]). Few authors proposed other criteria, such as sources of value in a product-service systems [5,14,30], before-the-event techniques of cleaner production [32], design strategies for product life extension [33], cycle of product/component/material circulation in material loops [5], or mixed criteria [12]. However, the typologies are somewhat overlapping, and the distinction criteria are sometimes blurred. An overview of the circular business models, systematized according to the ReSOLVE framework, is presented in Table 3.| Classification Criteria | Model | Literature Sources | Explanation | Example(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regenerate | Energy recovery | Damen [27]; Lacy et al. [28] | The conversion of non-recyclable waste materials into useable heat, electricity, or fuel | Ralphs and Food 4 Less installed an “anaerobic digestion” system |

| Circular Supplies | Lacy et al. [28]; EMF [23] | Using renewable energy | Iberdrola | |

| Efficient buildings | Scott [3] | Locating business activities in efficient buildings | Phillips Eco-Enterprise Center | |

| Sustainable product locations | Scott [3] | Locating business in eco-industrial parks | Kalundborg Eco-industrial Park | |

| Chemical leasing | Moser and Jakl [34] | The producer mainly sells the functions performed by the chemical, so the environmental impacts and use of hazardous chemical are reduced | Safechem | |

| Share | Maintenance and Repair | Lacy et al. [28]; WRAP [76]; Bakker et al. [33]; Planing [5]; Damen [27] | Product life cycle is extended through maintenance and repair | Patagonia, Giroflex |

| Collaborative Consumption, Sharing Platforms, PSS: Product renting, sharing or pooling | Lacy et al. [28]; Lacy et al. [25]; WRAP [76]; Planing [5]; Tukker [36]; Jong et al. [14] | Enable sharing use, access, or ownership of product between members of the public or between businesses. | BlaBlaCar, Airbnb, ThredUP, | |

| PSS: Product lease | Tukker [36]; Jong et al. [14]; WRAP [76]; | Exclusive use of a product without being the owner | Mud Jeans, Dell, Leasedrive, Stone Rent-a-PC | |

| PSS: Availability based | Van Ostaeyen, et al. [31]; Mentink [11] | The product or service is available for the customer for a specific period of time | GreenWheels | |

| PSS: Performance based | Van Ostaeyen, et al. [31]; Zairul et al. 2015 [52] | The revenue is generated according to delivered solution, effect or demand-fulfilment | Philips’s “Pay per Lux” solution; the need for new housing model for young starters in Malaysia | |

| Incentivized return and reuse or Next Life Sales | WRAP [76]; Mentink [11]; Lacy et al. [25]; Damen [27] | Customers return used products for an agreed value. Collected products are resold or refurbished and sold | Vodafone Red Hot, Tata Motors Assured | |

| Upgrading | Planing [5]; Mentink [11] | Replacing modules or components with better quality ones | Phoneblocks | |

| Product Attachment and Trust | Mentink [11] | Creating products that will be loved, liked or trusted longer | Apple products | |

| Bring your own device | WRAP [76] | Users bring their own devices to get the access to services, | Citrix pays employees for bringing own computers | |

| Hybrid model | Bakker et al. [26] | A durable product contains short-lived consumables | Océ-Canon printers and copiers | |

| Gap-exploiter model | Bakker et al. [26]; Mentink [11] | Exploits “lifetime value gaps” or leftover value in product systems. (e.g., shoes lasting longer than their soles). | printer cartridges outlasting the ink they contain | |

| Optimise | Asset management | WRAP [76] | Internal collection, reuse, refurbishing and resale of used products | FLOOW2, P2PLocal |

| Produce on demand | Renswoude et al. [7]; WRAP [76], Scott [3] | Producing when demand is present and products were ordered | Alt-Berg Bootmakers, Made, Dell Computer Company | |

| Waste reduction, Good housekeeping, Lean thinking, Fit thinking | Renswoude et al. [7]; Scott [3]; El-Haggar [32]; Bautista-Lazo [35] | Waste reduction in the production process and before | Nitech rechargeable batteries | |

| PSS: Activity management/outsourcing | Tukker [36] | More efficient use of capital goods, materials, human resources through outsourcing | Outsourcing | |

| Loop | Remanufacture, Product Transformation | Damen [27]; Planing [5]; Lacy et al. [25] | Restoring a product or its components to “as new” quality | Bosch remanufactured car parts |

| Recycling, Recycling 2.0, Resource Recovery | Lacy et al. [25] Damen [27] Planing [5]; Lacy et al. [28] | Recovering resources out of disposed products or by-products | PET bottles, Desso | |

| Upcycling | Lacy et al. [28] Mentink [11]; Planing [5] | Materials are reused and their value is upgraded | De Steigeraar (design and build of furniture from scrap wood) | |

| Circular Supplies | Renswoude et al. [7]; Lacy et al. [28] | Using supplies from material loops, bio based- or fully recyclable | Royal DSM | |

| Virtualize | Dematerialized services | WRAP [76]; Renswoude et al. [7] | Shifting physical products, services or processes to virtual | Spotify (music online) |

| Exchange | New technology | EMF [6] | New technology of production | WinSun 3D printing houses |

3.4. Conceptual Models

The relationships between constituent elements of a circular business model have been conceptualized in the literature. Every business model is both linear and circular to some extent [7,11]. This is because every company optimizes its processes, virtualizes products or processes (using e-mails instead of traditional letters) and/or uses some resources from material loops, and thus introduces some principles of the circular economy, albeit not necessarily deliberately. Renswoude et al. [7] put it differently—“100% circular business models do not exist (yet). Not creating any waste at all is difficult to achieve for physical and practical reasons (p. 2)”. For this reason, the main conceptual frameworks of business models apply to the circular economy. However, some frameworks of circular business models have been developed for either type.There are quite many conceptual frameworks of business models in general [75,77,78,79,80,81,82]. Thus, a further systematization became a reasonable direction of research. And so, there are two more comprehensive propositions, one by Wirtz [9], and one by Osterwalder and Pigneur [8]. Wirtz (2011) [9] made a systematic overview of the business model concept, and proposed an integrated business model consisting of nine partial models divided into three main components—strategic, customer and market, value creation. The strategic component comprises three models regarding the strategy (mission, strategic positions and development paths, value proposition), resources (core competencies and assets), and network (business model networks and partners). The customer and market components consist of customer model (customer relationships/target group, channel configuration, customer touchpoint), market offer model (competitors, market structure, value offering/products and services), and revenue model (revenue streams and revenue differentiation). The value creation component encompasses production of goods and services (manufacturing model and value generation), procurement model (resource acquisition and information), and financial model (financing model, capital model and cost structure model).

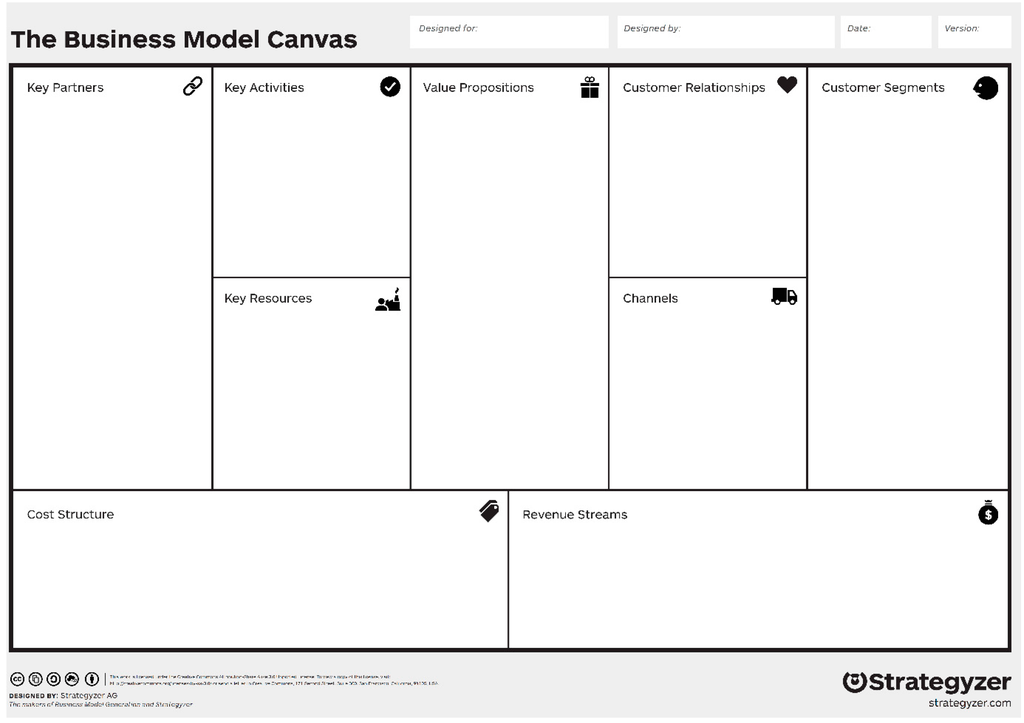

A more recognized and applied framework of a business model distinguishes nine building blocks [83], and is conceptualized as the business model canvas (BMC) [8]. The BMC consists of [8,10]:

- (1)

- Customer segments that an organization serves

- (2)

- Value propositions that seek to solve customers’ problems and satisfy their needs

- (3)

- Channels which an organization uses to deliver, communicate and sell value propositions

- (4)

- Customer relationships which an organization builds and maintains with each customer segment

- (5)

- Revenue streams resulting from value propositions successfully offered to customers

- (6)

- Key resources as the assets required to offer and deliver the aforementioned elements

- (7)

- Key activities which are performed to offered and deliver the aforementioned elements

- (8)

- Key partnerships being a network of suppliers and partners that support the business model execution by providing some resources and performing some activities

- (9)

- Cost structure comprising all the costs incurred when operating a business model

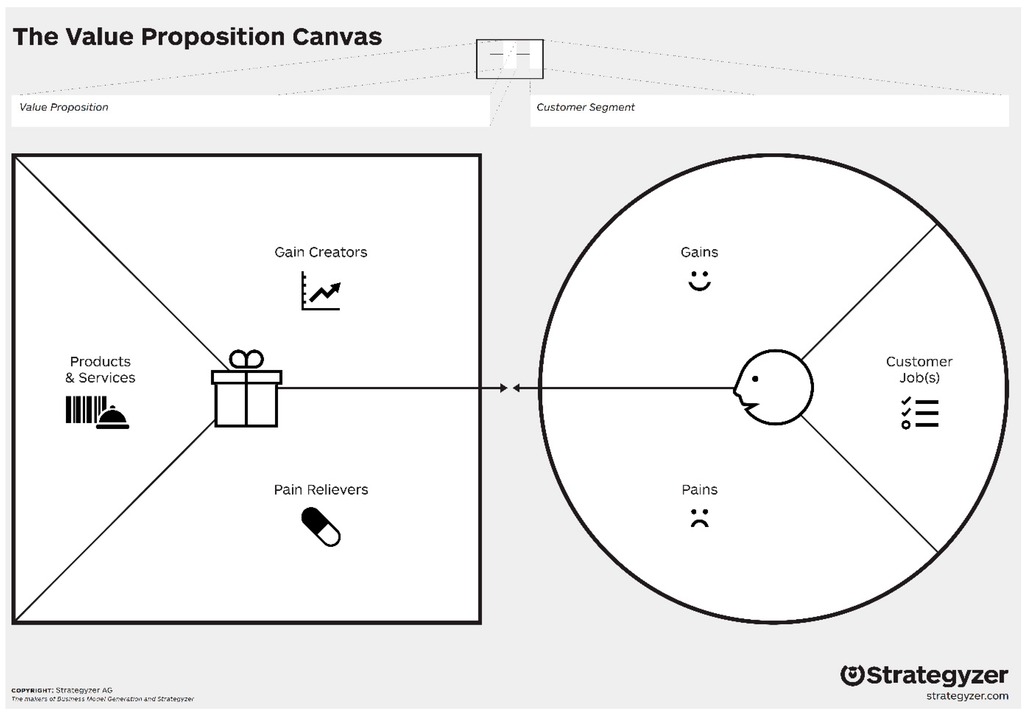

Most recently, value proposition design has been developed, and comprises of six building blocks, which are a detailed description of the two BM canvas blocks—value propositions and customer segments [37]. Value proposition is composed of the products and services offered to the customer, the relievers of customers pains, and the creators of customer gains pertaining to the tasks and jobs he or she needs to accomplish with the assistance of the offered product or service. Thus, on the customer’s side are the jobs, pains and gains related to doing the jobs. The visualization of both canvases are presented in Figure 2.

Some other conceptual frameworks exist in the literature related to sustainability. For instance, Stubbs and Cocklin [38] developed a case study-based conceptualization of a sustainability business model, consisting of two types of attributes—structural and cultural ones. Each type has its economic, environmental, social, and holistic characteristics. Structural attributes are depicted by:

- Economic characteristics, such as external bodies expecting triple bottom line performance, lobbying for changes to taxation system and legislation to support sustainability, keeping capital local

- Environmental characteristics, such as a threefold strategy (offsets, sustainable, restorative), closed-loop systems, implementation of services model, operating in industrial ecosystems and stakeholder networks

- Social characteristics, such as understanding stakeholder’s needs and expectations, educating and consulting stakeholders

Holistic characteristics, such as cooperation and collaboration; triple bottom line approach to performance; implementing demand-driven model; adapting organization to sustainability.

Cultural attributes are depicted by:

- Economic characteristics, such as considering profit as a means to do something more (“higher purpose”), not as an end, which is also a reason for shareholders to invest

- Environmental characteristics, such as treating nature as a stakeholder

- Social characteristics, such as balancing stakeholders’ expectations, sharing resources among stakeholders, and building relationships

- Holistic characteristics, such as focusing on medium to long-term effects, and on reducing consumption

Most recent contributions to conceptual models concern the dynamics between components of the business model. For instance, Roome and Louche [39] developed process model of business model change for sustainability, which explains how new business models for sustainability are fashioned through the interactions between individuals and groups inside and outside companies. Gauthier and Gilomen [40] analyzed transformations of the elements of sustainable business model and identified a typology of such changes (see Subsection 3.8 in this paper). Abdelkafi and Täuscher [41] developed a system dynamics-based representation of business models for sustainability. Not only has the dynamic of internal business model components been researched, but also the dynamics in relation to the business model environment. One of the key issues in this regard pertains to networks. Jabłoński [42] outlined the process of transition from an idea to the operationalization of the business model by searching for business model components from the network. However, the static approach is also being investigated. For example, Upward and Jones [43] developed the strongly sustainable business model ontology. Another approach proposed by Bautista-Lazo and Short [84] conceptualized an All Seeing Eye of Business model, which addresses the types of waste and their potential as a profit or loss generator.

3.5. Design Methods and Tools

There are several design methods and tools for the business model in the literature. Some of them focus on enhancing the design process [3,7,8,10], and others are used in particular situations and for particular business models [32,42,46].Joustra et al. [16] and Jong et al. [14] identified five steps to support for small and medium enterprises (SMEs) to enter the circular economy. The first two steps comprise reading about the CE, and learning about the readiness of the company, partners and stakeholders in the supply chain for CE. The next two steps suggest evaluating redesign opportunities that might bring the products into a more circular business model, and to understand the service that a company could potentially deliver and how the model needs to be redesigned to enable this. The last step tests whether the value delivered is the value that customers expect and will pay for.

Scott [3] proposed the 7-P model as a starting point toward understanding and applying the mechanism of the circular economy in a business. This model takes the practitioner’s approach and describes seven main components, which can be divided into three steps. The first is to learn and understand the fundamentals of the circular economy, and what the change will concern, and decide on establishing sustainability as an objective (prepare). The next step is to organize and implement the mechanisms of the circular economy related to the process, preservation, people, place, product, and production. The last step is to enable and support implementation of CE, mainly through building teams and managing change (People).

Renswoude et al. [7] developed the business model scan, a methodology to enhance a transition of the company into a more circular form. It consists of six process stages about which many questions are asked. Those questions are related to value proposition, design, supply, manufacturing, use, and next life. Osterwalder and Pigneur [8] proposed five stages of business model design process, encompassing mobilize, understand, design, implement, and manage. This methodology is supported by the business model canvas (described in Section 3.4). BMC has been applied to research and design circular business models [10,11]. Jablonski [42] distinguished eleven stages of the design and operationalization of the company’s technological business model embedded in the network. Parlikad et al. [45] identified the information requirements for end-of-life decision making and established a possible set of characteristics of a lifecycle information system to support management. They also reviewed existing product lifecycle information systems and divided them into two categories. Design/disassembly data-sharing systems encompass: Inverse Manufacturing Product Recycling Information System (IMPRIS), Recycling Passport, Products Lifecycle Management System (PLMS), Integrated Recycling Data Management System (ReDaMa). Lifecycle information monitoring systems comprises of: Information System for Product Recovery (ISPR), Life Cycle Data Acquisition System (LCDA), Green Port [45]. Cleaner production audits are undertaken to identify opportunities for cleaner production. The methodology for the cleaner production opportunity assessment has been outlined by El-Haggar [32] (p. 29), and consists of many activities related to and focused on the following: team, pre-audit, surrounding environment, operations and processes, inputs and outputs, wasteful processes, material and energy balance, opportunities, priorities, implementation, assessment, process sustainability, sustainable development. Another important method is life cycle assessment [85] which is explained as “a tool for the analysis of the environmental burden of products at all stages in their life cycle—from the extraction of resources, through the production of materials, product parts and the product itself, and the use of the product to the management after it is discarded, either by reuse, recycling or final disposal (in effect, therefore, ‘from the cradle to the grave’)” [46] (pp. 5–6). Scott [3] (p. 81) also suggests that environmental audits, such as compliance audit, waste audit, waste disposal audit, water audit, can be used. Mentink [11] discussed a few other methods and tools, such as: New Framework on Circular Design, Practical Guide for PSS Development, Circular Economy Toolkit, Play it Forward, 4-I Framework, and Sustainable Business Model Canvas.

3.6. Adoption Factors

Factors affecting CBM adoption are mostly related to general factors [5,47], human resources [3,16,28], political system and legislation [3,6], IT and data management [3,45], and business risks [11]. There are also crucial socioeconomic implications, justifying the efforts towards CE [4,7,22], and other enablers such as leadership, collaboration, motivation through the concept itself, and customer behavior [53].General factors encompass conditions which need to be fulfilled to secure profitability of closed circles. Winter [47] (p. 16) points out five of them: sufficiently valuable materials/products, control of product or material chain, ease of reuse, remanufacture or recycle materials/products, predictable demand for future products, keeping materials/products concentrated and uncontaminated. Planing [5], however, argued that customer irrationality, conflict of interest within companies, misaligned profit-share along the supply chain, and geographic dispersion could be the reasons for rejecting circular business models. Scheepens et al. [48] argue that transition to CE is impacted by different factors on several levels: societal, regulatory, services and infrastructure, and product and technology. Sivertsson and Tell [71] identified barriers to business model innovation in the agricultural context for each of the nine building blocks of the business model canvas (by Osterwalder and Pigneur [8]). Pearce identified six kinds of customers whose needs may be satisfied by the companies offering remanufactured products. These types comprise the customers who (1) need to retain a specific product because it has a technically defined role in their current processes; (2) want to avoid the need to re-specify, re-approve or re-certify a product; (3) make low utilization of new equipment; (4) wish to continue using a product which has been discontinued by the original manufacturer; (5) want to extend the service lives of used products, whether discontinued or not; and (6) are interested in environmentally friendly products [51]. Linder and Williander [18] outlined challenges regarding remanufacturing, such as: considerable expertise and knowledge of the product; efficient product retrieval; suitable types of products; risk of cannibalization if the new, longer-lasting products reduce sales of the previous products; fashion changes; a financial risk for the producer if the offer is to be rented; increased operational risk; lack of supporting law, policy and regulations; and compatibility with the business models of partners.

Regarding the role of human resources in a company shift towards the circular economy, various suggestions have been made. On the basis of successful waste elimination schemes, Scott [3] formulated general recommendations for creating teams related to team members and team size, volunteers, goals, motivation, maintaining links with organization, organizing team meetings, positive thinking, and leadership. Lacy et al. [28] (p. 18) identified five capabilities of successful circular leaders (business planning and strategy, innovation and product development, in sourcing and manufacturing, sales and marketing, reverse logistics and return chains). Other researchers also emphasized the role of leadership, mostly pertaining to the appreciation of the new strategic direction, understanding its benefits and risks, and the ability to establish a common understanding in the business [53,54].

Joustra et al. [16] (p. 11) identified eight elementary skills for any circular economy project team, such as: entrepreneurial and developing, craftsmanship aimed at product/services, systems thinking and capability of identifying causal loops, future oriented and out-of-the-box, celebrating diversity, addressing insecurities, designing circular systems, products and services, and being creative, innovative and connected. Laubscher and Marinelli [22] give some insights from the practice and emphasized the role of adequate culture adaptation and development of capabilities in a BM transformation towards CE. This can be obtained through dedicated training programs, performance and rewards schemes, personal targets and bonuses for sales managers.

Others argue that policymakers at all government levels (municipal, regional, national, and supranational) play an important role in the circular economy [3,6]. There are two broad and complementary policymaking strategies to accelerate the circular economy: fixing market and regulatory failures, and stimulating market activity by, for example, setting targets, changing public procurement policy, creating collaboration platforms and providing financial or technical support to businesses [6].

Parlikad, et al. [45] and Scott [3] (p. 79) argue that IT and data management systems are essential for the circular economy, because they allow to keep track of products, components and material data. This strongly supports effective reverse logistics systems, material loops (also cross-industry) and reuse of components.

Some business risks of service models (or PSS) have also been identified in the literature. They are related to the fact that (a) owning a product is preferred if the user is emotionally attached to the product or the product has an important intangible value, impacting, for instance, the owner’s social status; (b) result or function-oriented services need a good explanation and description, which may increase transaction costs; (c) the service provider must predict and control the risks, uncertainties and responsibilities related to selling a result-oriented service [11,14,16]. Moreover, validating a circular business model always has a higher business risk than validating a corresponding traditional, linear business model [18].

Regarding the impact of the circular economy, there are three main winners: economies, companies and user/consumers [3,4,7,55]. CE advantages for economies are related to e.g., the impact on economic growth, material cost savings, mitigation of price volatility and supply risks, significant job growth in services, employment market resilience [4,49]. Laubscher and Marinelli [22] point that companies can gain financial and reputational value. Others argue that CE will give the companies new profit possibilities, increase competitive advantage and build resilience against several strategic challenges [4,56,57]. Detailed advantages could concern: innovation and competitive advantage, additional revenue streams, long-term contracts, customer loyalty and feedback, multiple benefits of internal resource management, and beneficial partnerships throughout the value chain [7,58,59,60]. Customer and user benefits mainly comprise of increased choice at lower cost; however, there are also some social benefits, like a contribution against climate change [4,52].

Importantly, adaptation factors change in time and those changes also impact the evolution of business models [50].

3.7. Evaluation Models

The criteria for assessing the feasibility, viability, and profitability of circular business models must be adjusted to the micro, meso and macro-level of implementation [47]. On the micro-level Laubscher and Marinelli [22] argue for measuring the reduced ecological footprint, direct financial value through recovery of materials and assets, and top line growth through new business models. A more extended set of key performance indicators could encompass a percentage of: revenues from repairs, reused parts, refurbished products, recycled material used product value after period X, revenue from second-hand products, times of reuse of resource, technical lifetime value of by-products, by-products used, separability of resources, toxic materials used, and products leased [11]. Anderson and Stavileci [61] proposed several criteria for evaluation of the business model’s validity for the circular economy, such as: turnover possibility, margins, capital intensiveness, implementation time, dependence on supplier, possible usage of recycled materials, usage of unsustainable materials, benefits from additive manufacturing, percentage of lifecycle, product oriented, and service oriented. There are also some guidelines for accounting the costs of material flow (MFCA) [62,63,64].On the macro-level, there are several measurements for three CE principles [23]. Measurements concerning the principles of preservation and enhancing natural capital by controlling finite stocks and balancing renewable resource flow, comprise degradation-adjusted net value add (NVA) as a primary metric, and annual monetary benefit of ecosystem services, annual degradation, and overall remaining stock as secondary metrics. Measurements for the principle of optimization of resource yields by circulating products, components and materials in use at the highest utility at all times in both technical and biological cycles, encompass as a primary metric GDP-generated per unit of net virgin finite material input, and product utilization, product depreciation/lifetime, and material value retention or value of virgin materials as secondary metrics. Measurements for the principle of fostering system effectiveness by revealing and designing out negative externalities, consist of cost of land, air, water, and noise pollution, as a primary metric, and toxic substances in food systems, climate change, congestion, and health impacts as secondary metrics [23].

3.8. Change Methodologies

Scott [3] (pp. 103–109) argues that basic change management theories, like the Force Field Theory, Three-Stage Approach to Change Behavior, sources of staff resistance to change, can be successfully applied to manage the transition from a linear business model towards a circular one. However, other studies provide theories more specific to CE. For example, the model of the process of changing business model for sustainability explains how new business models for sustainability are fashioned through the interactions between individuals and groups inside and outside companies [39]. Gauthier and Gilomen [40] identified a typology of business model transformations toward sustainability:- (1)

- Business model as usual—if there are no transformations to business model elements

- (2)

- Business model adjustment—if marginal modifications to one element of BMs occur

- (3)

- Business model innovation—if major BM transformations were implemented

- (4)

- Business model redesign—if a complete rethinking of organizations’ BM elements results in radically new value propositions

4. Circular Economy and the Components of Business Model

4.1. Value Propositions Fitting Customer Segments (Value Proposition Design)

The core component of the circular business model is the value proposition. Circular value proposition offers a product, product-related service or a pure service [14]. This offer must allow the user/consumer to do what is needed, reduce inconveniences which the consumer/user would experience, and provide additional benefits [37].Circular products, although ownership-based [5], have several specific features related to the CE principles. Circular products enable product-life extension through maintenance, repair, refurbishment, redistribution, upgrading and reselling [5,7,28,33,45]. They are designed to enhance reusing, recycling, and cascading. This requires a modular design and choosing materials that allow cascading, reusing, remanufacturing, recycling, or safe disposal. Thus, such products are 100% ready to circulate in the closed material loops. Moreover, product design should allow using less raw material or energy or to minimize emissions [3,25,32]. Circular products can be also dematerialized and offered not as physical but as virtual products [4,7].

In a product-service system a company offers access to the product but retains its ownership. It is an alternative to the traditional model of “buy and own”. This is a way of reducing customer pains, creating gains, and getting the jobs done through offering product-oriented services or advice, use-oriented services including product leasing, renting, pooling, and pay-per-service unit, or result-oriented services, comprising outsourcing and functional result [14,25,28,30,36]. Some examples comprise: Philips pay-per light [22] or GreenWheels’ shared car use, hours of thrust in a Rolls-Royce, or “Power-by-the-Hour” jet engines [26].

Circular value propositions related to services may concern shifting their traditional form to a virtual one (e.g., virtual travel) [4,6,7].

Collaborative consumption related to product sharing/renting or product pooling can bring cost savings, services tailored for customer needs, and additional benefits. For instance, BlaBlaCar offers not only cheap transportation possibilities and route connections unavailable by public transport, but also social gains (see blablacar.com). Some other sharing-based value propositions concern sharing residence, parking, appliances/tools sharing, office, and flexible seating, which may require some specially developed platforms [4,7,28].

Usually there are some incentives offered to the users/consumers [76]: for example, buy-back programs like Vodafone—New Every Year/Red Hot [1]. In this case, incentives are a source of value for the customer (part of value proposition), and products, components or materials collected back contain a value retrieved by the company.

The value proposition must be appropriate for particular customer segments, for specific types of customers [51].

4.2. Channels

One of the strongest shifts towards a circular business model regarding channels is virtualization. This means that an organization can sell a virtualized value proposition and deliver it virtually (selling digital products, like music in mp3 format) and/or sell value propositions via virtual channels (online shops selling material products) [6]. Another possibility is to communicate virtually with the customer (e.g., using web advertisements, e-mails, websites, social media, video conferences) [23,69].4.3. Customer Relationships

Building and maintaining relationships with customers can underlie the main principle of the circular economy—eliminating waste—twofold. Those two options encompass producing on order, and engaging customers to vote for which product to make [7]. Additionally, a switch to recycling 2.0 may enhance social-marketing strategies and leverage relationships with community partners [25,69].4.4. Revenue Streams