Transport Management Systems (TMS)

good case on the TMS :

Get all the elements of your business under control centrally

TMS software focuses on transport logistics and coordinates control of consignments between order management systems, the warehouse, the distribution centre and the drivers.

TMS covers the four main processes of transportation management;

Planning, Execution, Follow up and Measurement.

Our TMS will integrate with routing and scheduling software, use pre prepared route templates or routes can be planned manually from a map display or paperwork.

Load / route details can be uploaded to drivers' phones and proof of delivery returned real time to the transport management system and the customers directly.

Monitor the progress of your drivers, be alerted to possible service issues and pro actively solve them before they become customer service issues.

Understand your productivity and costs, price your services more accurately, spot trends early and produce timely, accurate invoices that your customers will understand.

Load / route details can be uploaded to drivers' phones and proof of delivery returned real time to the transport management system and the customers directly.

Monitor the progress of your drivers, be alerted to possible service issues and pro actively solve them before they become customer service issues.

Understand your productivity and costs, price your services more accurately, spot trends early and produce timely, accurate invoices that your customers will understand.

Benefit your business by integrating your customers and suppliers into our user friendly Transport Management System. Simplify your office procedures, improve the efficiency of your transport operations and enjoy reduced costs and increased profits that will follow.

TrackTrans' Transport Management System enables you to:• Create, export, POD, Price and Invoice all from one package

• Give great customer service, let your customers see the status of their consignments Live online

• View the days progress at a glance through the colour coded diary screen

• Access your TMS anywhere in the world from any internet enabled PC

• In conjunction with our POD android app receive complete signatures, co-ordinates and times

• Link your TMS with your customers ERP/TMS solution, receive live electronic jobs, return real time status and PODs

• All your data backed up and protected on our specialist servers

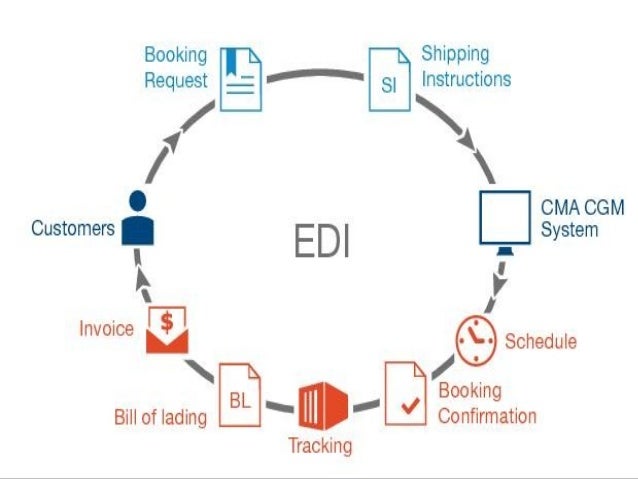

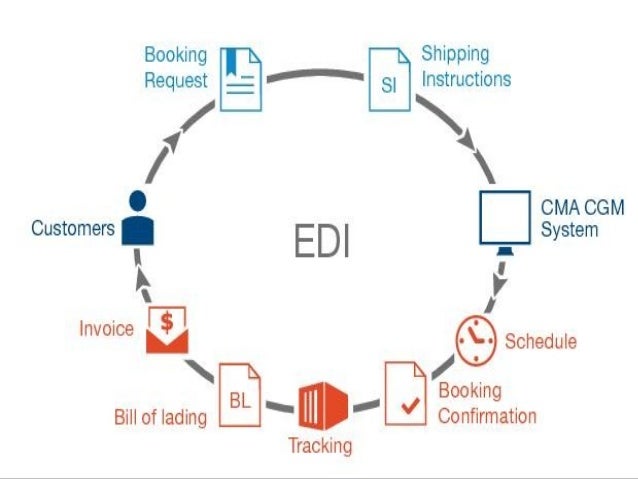

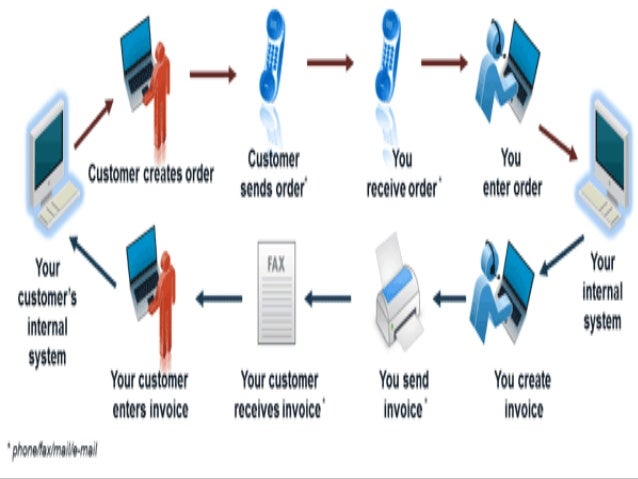

Order entry

Create complete jobs with references, extra requirements, instructions, dates/times and many other details or, receive jobs from your customers electronically through our EDI Interface.• Manual - Simple and quick to enter essential information

• Ideal for use in conjunction with 'in house' ERP systems

• Maintained Customer, Staff, Vehicle, Subcontractor, collection and delivery address lists cut down key strokes and enhance accuracy

Routing and Scheduling

Table sorting, colour coded diary screens and advanced date/time criteria allow jobs to be organised and scheduled with the minimum of fuss.• Colour coded diaries screen shows live reports of arrivals, problems and completed deliveries

• All tables can be sorted and organised by your criteria

• Organise by area, size of load, date/time, etc...

Load creation

• 'Own fleet' - allocate loads to vehicles, trailers and drivers• 'Subcontractors' - allocate loads to subcontractors

• Communicate load instructions direct to vehicles and subcontractor systems via the TrackTrans 'Message Hub'

Status update/POD

• In-cab solutions allow Driver’s to return POD’s, signatures and other status directly from their mobile phone*. Ideal for ‘Own fleet’ and ‘owner drivers’.• Subcontractors can update status and POD information via a web interface on the TrackTrans 'Message Hub'.

• No systems interface required, just an internet connection and web browser - everyone can cooperate

• For larger subcontractors a simple XML interface to the TrackTrans 'Message Hub' gives 'real time' status and POD information

Costing

• Purchase orders – send the agreed rate for jobs along with the job information• Self Billing – costing system uses purchase orders to pre approve third party invoices

• Purchase logging – record purchase invoices on arrival at your premises before distribution to the operators. Eliminate nasty surprises.

Accounting

• Price jobs and Invoice customers by date, batch reference or purchase order• Prepare detailed schedules to support summary financial invoices

• Optional integration with QuickBooks

• Integrate working time information with your payroll system

Reporting and Searching

• Search by dates, address, driver or any other aspect of a job/load• Custom reports – Choose your own headings and report on any aspect of a jobs status. Reports received in spreadsheets format to allow full editing and manipulation

Special reports for:

• Progress chasing – check for status and POD information against ETA’s and ETD’s

• Subcontractor costing and Gross Profit details

• Vehicle, trailer and driver utilisation

• Unpriced, un-costed and un-billed jobs

Working Time and Hours recording

• Record working time against drivers and extra men.• Record warehouse hours against customers/warehouseman and invoice out with other work

• Holiday book allows annual leave, sickness, maternity leave etc. to be recorded. Holiday chart lets you view leave/sickness at a glance and plan for potential staffing shortfalls and

Administration

Maintains lists of:• Users

• Contacts

• Employees

• Vehicles, etc...

System Architecture

• SQL database backend• Browser based application

• Android, iOS and Windows compatible apps for handheld smartphones

• 'Message Hub' XML based

Service Options & Charging

Need to collect your PODs in real time but think the cost is too high?

A lot of people think that a real time Proof Of Delivery system is expensive, but with TrackTrans that isn’t the case.Proof Of Delivery is now a real possibility, even for those who are on a limited budget. Our new, electronic POD app offers a real alternative to the traditional paper based systems.

All you need to do is download the TrackTrans proof of delivery app onto your Android, iOS or Windows mobile phone and you’re good to go. Installing the software onto a compatible smart phone is fast and easy, and it's a simple process to go from running one handset to one hundred.

Our real time Proof Of Delivery app is designed to run alongside our Transport Management System (or interface to your existing TMS). It allows jobs to be sent easily from your TMS to the drivers mobile quickly. Drivers can then access full details including the address, references, quantities and instructions.

Free up your office staff - have your drivers and subcontractors enter POD's themsleves - Real Time

The TrackTrans electronic POD system gives you:

• live updates on arrival and waiting times

• Instant confirmation of deliveries or problems

• POD's complete with names and signatures

• Realtime updates on Vehicle Location

Are your phone bills too high?

Do you find yourself repeatedly spelling out addresses over the phone?

Do you feel there should be an easier way?

Data communication with TrackTrans could be the answer you're looking for.

The TrackTrans app ( Android, iOS, Windows ) allows jobs to be sent, quickly and easily, from your TMS straight to your drivers' mobiles.

As well as full address details, references, and quantities, instructions can be added easily and sent to the drivers' handsets.

Receive instant acknowledgements from your drivers for the jobs sent to them.

Designed to run alongside your existing Transport Management software (or TrackTrans' Transport Management System).

Simple and intuitive to use, drivers quickly get accustomed to using handheld devices, saving time, money and hassle.

Satellite Navigation & Traffic Alerts

Sygic the best in offline Satellite navigation - fleet version with road restrictions

Reliable offline app, no internet needed

Reliable offline app, no internet needed

Sygic GPS Navigation is an offline navigation app.

This means that all the important stuff like maps, millions of points of interest and software for route calculation, are all stored on the phone.

So even if there is no mobile internet you can count on Sygic to guide you to your destination.

High-quality maps & Free updates

High-quality maps & Free updates

Great navigation takes accurate and up-to-date maps.

Because roads are constantly changing Sygic offers frequent map updates at no additional cost.

Sygic provides the latest maps from premium providers.

Sygic GPS Navigation is the right app for your next trip.

Turn-by-Turn voice guidance

Turn-by-Turn voice guidance

Sygic GPS Navigation will find the best route for you, whether you are driving or walking.

Each mode offers convenient directions specifically tailored for drivers or pedestrians.

You will never get lost again and always get to your destination as quickly as possible.

3D buildings & landscape

3D buildings & landscape

A precise map is not enough to find your bearings easily in an unfamiliar city.

3D landmarks, buildings, parks, mountains and valleys, and smooth map movement.

Driving with Sygic GPS Navigation is both practical and enjoyable.

Warehouse Management - WMS

Goods Inwards

• EDI - receive data from supplier systems via the TrackTrans 'Message Hub' - simple XML interface. Create pre-advices for manpower and space planning

• Manual - Simple and quick to enter essential information

• Customer, Supplier, Stock codes, Packing units, SKUs, Serial numbers. etc...

• Bar Codes - Scan goods in using supplier bar codes or prepare goods in labels with system generated bar codes

• Holding area - unload directly to a holding area for quick turnaround and accurate checking and labelling

Put Away

• Stock locations - all pallet locations and stock holding areas defined with system generated bar coded location labels

• Pick bays replenished first in put away process

• Optimise Locations - Goods directed to vacant locations according to speed of throughput and proximity to pick bays

• Integrate replenishment with the put away process - utilise the return leg of the fork lift movement for pick bay top up and location management

Picking

• Multi task picking - pick lists for different customers can be run concurrently

• Pick bays - used to manage break bulk quantities and pick lists prepared to use bins before breaking boxes or pallets

• Pick lists - optimised to reduce picking tasks to the minimum and to maximise productivity

• Stock rotation - stock utilised on a 'First in, First out' basis. Can be overridden if other factors need to be considered

• Line picking - pick orders directly during the unloading process

Goods Out

• Shipping labels - produce shipping labels and record consignment weight and dimensions

• Scan out - confirm loading of consignments with scanning of shipping labels, overscan to consolidate shipping labels

• Create Consignments in TrackTrans TMS

• Manage Delivery process to final consignee with Proof Of Delivery

Stock Check

Blind scan of stock by:

• Customer

• Area

• Range of locations

• Entire warehouse

• Scan results compared with 'Book' stock figures and reconcile variances

• Facility to update stock with 'actual' figures and maintain an audit trail of all adjustments

Accounting

• Invoicing - Prepare detailed schedules to support summary financial invoices

• Integrate working time information with your payroll system

Management reporting

• Stock reports

• Empty locations

• Pick bay replenishment requirements

• Enquiries - on all aspects stock movements

Administration

Maintains lists of:

• Customers

• Locations

• SKU's

• Employees

• Users, etc....

System Architecture

• SQL database backend

• Browser based Java application

• C++ for WiFi handheld devices

• 'Message Hub' XML based

Service Options

• Hosted service on a 'Pay as you go' basis - no up front costs - no long term contract

• Licensed to run on your hardware

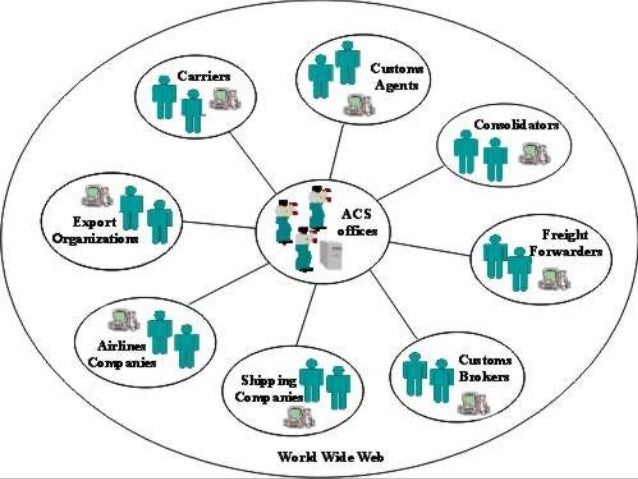

Messaging - EDI

Consignment information, status and Proof Of Delivery (POD) updates

Connecting consignors and consignees with all the transport contractors in their supply chain

The Message Database is the TrackTrans integration service that communicates consignment data between transport contractors in a supply chain. End to End visibility of consignment movements in the delivery process enables the performance monitoring and management that delivers reliable and dependable service

Outputs:- Consignment Information

Inputs:- Status and Proof Of Delivery (POD) updates from the hub

Outbound

EDI – send consignment data from your existing systems via the TrackTrans ‘Message Hub’ – simple XML interface.

TrackTrans Integration services ensure that all the necessary data is collated and transmitted to the transport contractors.

Simple connection to the TrackTrans TMS if a disposition module is required to enhance the capabilities of the existing system.

Project Logistics

Internet based, no start up investment, no long term contract.

Deploy a complete management and visibility solution for all contractors on your project.

Set up

All the TrackTrans software is multi language - if we don't have the language you need, it can be made available in a few days

Training

Full step by step guides and flash videos are available for downloading

Implementation

Use whatever TrackTrans products you need in different locations:

• Warehouse management

• Transport management

• Vehicle Tracking

• Messaging

• Proof Of Delivery

Reporting

The TrackTrans databases have integrated report engines for user defined reporting. Data can be exported in a variety of formats (.csv .xls(x) etc......)

Support

24 hours a day, 7 days a week, 365 days a year and all hosted in a secure Tier3 facility

Working Time

Working Time compliance made easy

Follow the simple instructions to create users and start recording right away.

Gives drivers their own sign on and allow them to complete their own timesheets remotely, via the internet.

Download all your information for a given period to an Excel spreadsheet.

Go a step further and download our simple and easy-to-use handheld software and record drivers hours in real-time.

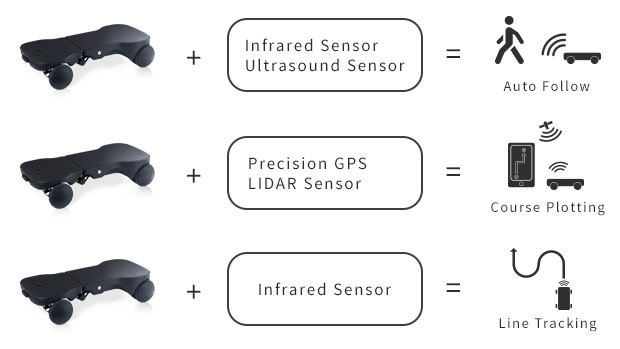

Choose a vehicle tracking system that fits your business and improves your performance.

Benefits: • View all your vehicles from any computer in real-time

• View all your vehicles from any computer in real-time

• Track your employees, vehicles and goods

• Have the ability to update your customers accurately

• Make better decisions when allocating jobs

Properly managed, delivery staff can be your company's biggest asset.

Without it they could be your biggest liability

Map displays showing:

• The position of all your vehicles refreshed every 10 minutes.

• The complete route for a specified vehicle on a specified date.

• The current position of a specified vehicle on demand.

See exactly what your vehicles and drivers are doing with TrackTrans.

It costs less than you might think, while reducing your operational costs and enabling you to provide an unparalleled service to your customers.

Specification

The vehicle tracking service is Internet based, all you need is a PC, an internet browser (Microsoft Internet Explorer, Mozilla Firefox etc...), and a broadband connection. No complicated installation to maintain; a ‘home spec’ PC bought and supported locally will be more than adequate.

• Time limited access to the displays for customers and the emergency services.

• Data kept for twelve months with the option to archive to DVD.

• Printed reports of all the data and the map displays are also available

XXX . V Logistics Strategies for Business

the solution of study case logistics :

How to Develop a Winning Logistics Strategy

For any company that is in the business of providing a variety of products and services to costumers, it is of crucial importance to the health of that business to implement a logistics strategy that will help keep service levels at their highest at all times, no matter what changes might be happening in other areas of the business organization. This is an even bigger imperative for companies that are more complex in structure, or that may have a very fluid or fluctuating supply chain, or that have specific product lines, specific countries or specific customers to cater to.

the solution of study case logistics :

How to Develop a Winning Logistics Strategy

For any company that is in the business of providing a variety of products and services to costumers, it is of crucial importance to the health of that business to implement a logistics strategy that will help keep service levels at their highest at all times, no matter what changes might be happening in other areas of the business organization. This is an even bigger imperative for companies that are more complex in structure, or that may have a very fluid or fluctuating supply chain, or that have specific product lines, specific countries or specific customers to cater to.

But what exactly should logistics professionals focus on to improve their business’ effectiveness? Should you spend more time identifying structural improvements to increase speed of production? Should you focus primarily on minimizing logistics costs? Or should you first spend more of your focus on identifying the best high-level organizational objectives and determine whether your overall logistics strategy contributes to that objective? Which tactic is right for your business and in what circumstances?

To help you evaluate your choices and even come up with some new ideas, we’ve asked a panel of logistics strategy experts the following question:

“What’s your top tip or idea for a new business (or even an established organization) looking to create or improve their logistics strategy to make it more effective?”

We’ve collected and compiled their expert advice into this comprehensive guide to effective logistics management strategy. We hope it will help you maximize your company’s logistic resources and ultimately take your logistics strategy to the next level.

1. we also championed the concept of applying logistics technology to all aspects of supply chain management, from the largest ERP systems to the smallest SaaS solutions. When it comes to an effective logistics strategy . go to start practicing demand-driven logistics if you have not already done so.

The importance of better matching demand for your products to your supply goes far beyond reducing your transport spend.

When a company begins practicing inbound logistics or demand-driven logistics, transportation costs are reduced but the savings of replacing inventory with information, and providing better customer service to your customers, is even more important.

Beyond that important result, aligning your business to practice demand-driven logistics moves logistics management out of the functional silo and provides strategic benefits to the entire enterprise .

2. we are constantly monitoring the pulse of the supply chain industry for leading edge trends and best practices that Supply Chain Visions can bring to their clients. I can share with business professionals looking to create an effective logistics strategy…

Comes from many years working as a consultant to companies in the warehousing and supply chain areas. It is a rather simple, and extremely effective approach that is way too frequently overlooked, misunderstood, or simply not well executed.

New and existing companies should take time to understand the essence of Sales and Operations Planning or S&OP. Many times I see companies who “think” they know S&OP, and some who practices a form of S&OP without actually naming it. But I don’t see a lot of companies practicing it effectively.

S&OP simply defined is a strategy where all of the primary functions (Sales, Marketing, Product Management, Manufacturing, Warehousing, Procurement, Finance, Transportation) of the business come together as a team (face to face or via a communications link) to review, discuss and plan business activities. Note here that it does not simply include Sales and Operations, but must include all parties who impact, or are impacted by, the regular activities of the business.we all understanding a common set of goals (customer satisfaction, profitability, improved sales, etc.), and agreeing to work together to achieve those goals. The meeting should be held as frequently as practical, and the team should have a set of tools, KPIs and reports, to assist in regular checkups and notifications. Meetings should be focused and short, they should be about cooperation and strictly avoid confrontation. Yes, we will discuss what went wrong, but with a focus on the “why” and “how” of improvement and eliminating the issue. It should be more about planning for what is coming in the short and long term, and how the team will address it.

There must be commitment by all parties to move past the functional silos that continue to haunt companies. It must, over time, become an ingrained component of the company’s culture.

Properly executed, a solid S&OP process can do more than any other single logistics strategy to improve the odds of success. Once the “team” is in sync, the individual functional areas can turn to focusing on how to most effectively address their part of the process, understanding fully what the goals are.

Without S&OP it has been proven that most functions will create their own goals, but they are likely to not be aligned with the rest of the business. For example; A DC achieving a high fill rate for customer orders may not be good for the business if doing so comes at a high cost to the rest of the business. S&OP can help ensure that all of the logistics related activities are tuned to getting the highest fill rate possible in the most economic and efficient manner.

3. we have to various logistics positions of increasing responsibility in inventory management, order processing, and transportation and distribution center operations management . the solution we must is to acquire an experienced logistician who has great interpersonal skills, is well connected to the logistics/supply chain world (a CSCMP member of course!), is a proven leader, and has solid financial acumen.

4. this now the

international companies on Logistics and Supply Chain projects in all sectors including pharmaceutical, retail, automotive, high technology, food, drink and professional services .

Logistics and supply chain strategy can be summarized as the operational execution of the business mission.

So firstly understand the business mission, reflect on the Corporate strategy of the organization and plan accordingly. Secondly, recognize an “average” supply chain means 50% of customers are sick of your service and 50% you are spending to much money on! A focused competitive strategy is required so liaise and discuss with the marketing and sales functions of your business. So you need to segment your customers and products so that you can develop individual supply chains to create maximum value at the lowest possible cost for each of these groups. Thirdly, now for a supply chain strategy to really work, four areas need to be designed.

Your supply chain processes, the supply chain infrastructure including where you locate facilities and also what equipment is used, your supply chain information systems, and finally the supply chain organization. This is how you organize your people.

So in summary, start with the corporate strategy, identify how you compete in various markets and understand the competitive strategy, develop the supply chain strategy to serve these markets by tailoring your Supply Chain Processes, infrastructure, information systems and organization and people.

5. The most important idea about a business’ logistics plan is…

that it should always be subordinate to corporate strategy. For example:

- If your company’s strategy is to always be the low price leader, then the prime goal of the logistics strategy is to move stuff at the lowest possible cost.

- If your corporate strategy is based on agility and the movement of goods faster than competitors, then logistics strategy is based on speed rather than cost.

- If your company sets the standard for quality, then the logistics goal is to have100% perfect orders and to do whatever it takes to correct any error.

- If your company is growing by merger, one logistics strategy is to integrate the operations of the new acquisition into the existing logistics program.

- If your corporation is judged by its return on invested capital, then the logistics strategy is to remain as free of assets as possible by finding short term leases for warehouse real estate and transport equipment.

6. for creating an effective logistics strategy is…

First define what you are trying to accomplish, what goals you are trying to achieve. Your logistics / supply chain strategy supports the goals of the business, so your supply chain strategy must align with and help achieve the organization’s goals. The second step is to articulate how the supply chain strategy works to achieve the higher level goals.

For example, if speed to market is a goal, the supply chain strategy will look different than one where the goal is to be the low cost supplier.

7. When it comes to any company’s logistics management strategy…

There is a critical need in today’s hyper-fast, online environment to meet the expectations of clients. Finding a faster, more efficient means of handling products is important for supporting a successful organization, and a well-run supply chain is vital to the success of a business. Starting with a great solution or upgrading the supply chain management system is essential in order to compete and can provide a substantial boost to productivity. The potential for supply chain disruption comes from unexpected weather, natural disasters, political upheaval, economic crises and other “black swan” or unique events that can ruin a start up and cripple an existing business.

The most important tip in mitigating the potential negative outcomes of supply chain disruptions is doing effective and careful pre-planning. Benjamin Franklin said, “An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.” That quote absolutely applies to supply chain logistics. Each company has a special “finger print” with its products; some are sensitive to spoilage, some are fragile electronics and others require more human labor. In order to react swiftly and decisively, a plan supported by the right solution is critical to an organization. With corporations, suppliers and manufacturers situated in different parts of the globe, you need technology that can link everyone together in a way that provides consistency, streamlines processes and enhances visibility to meet challenges in real time. A business is only as successful as its supply chain. Pre-planning now and elevating this to the executive team in an organization today can eliminate the majority of customer service issues tomorrow.

Finding the right solution can be game-changing in today’s frantic, uncertain market. Potential problems lie within mismanaged warehouse processes, inadequately tracked fleets and their inventory, scattered inventory, lackluster transportation management or some other supply chain conundrum.. Many warehouses handle massive numbers of shipments every year and in an economy that has seen less frequent hiring of additional help, much of the focus has been placed on maximizing the potential of the workforce. Having fewer hands to help receive and move shipments places an increased premium on accuracy and speed. This applies closely to organizations that deal with perishable and time-sensitive products, such as food, beverages or anything that involves the cold chain. Within these organizations, careful tracking of shipments is essential.

Many organizations still rely on “tribal knowledge” for this sort of information, but even the best memories fail. Manual processes tend toward error, but a system that centralizes information and helps automate the supply chain provides a level of support and real-time access to information that can help a business reach its maximum potential with minimum investment of time, planning and solution implementation.

Planning for the future with innovation is the key, whether it’s through whipping your company fleet into shape with fleet management software, keeping close tabs on product through inventory management solutions or maximizing every square foot of space with improved warehouse management. Innovation is hitting the market as solutions centralize data and provide real-time access to what you need to know, whether you’re in the office, down the street or several continents away.

Technology is linking vendors to customers and customers to shippers through an interlinked web that promotes the sort of fast, adaptable response that sets a business ahead of its competitors. Today’s logistics is mobile-enabled, connected and requires much more than the pencil-and-clipboard style of management from years past. Google CEO Eric Schmidt has said the world now creates as much data in a span of 48 hours as all of human civilization managed to produce from the beginning of history until 2003. Planning and leveraging that Big Data to better understand and propel a business means building a sustainable future.

8 . logistics management explain has included transportation planning and process management, engineering, continuous improvement and Transportation Management System (TMS) process design and integration.

The best idea I can share with business professionals for better understanding how logistics strategies work is…

Logistics strategy is the science of evaluating the most cost effective methodology of distributing goods to market while achieving service level objectives. When establishing an effective logistics strategy, you need to understand to what degree logistics impacts your operations and your customers’ operations. How crucial is timely delivery to your inbound and outbound deliveries, and what constraints exist, such as budget, resources and existing network of providers. If you choose to outsource your logistics operations, make sure you use an organization that will work with you hand-in-hand to co-manage your logistics, so that you keep all your front-line carrier relationships and control. Work with an organization that doesn’t see you as a “project” but as a “partner” who will share with you their best practices and understanding of emerging trends. This partnership-type relationship ensures success within your logistics operations.

9. in future at the opportunity to work in virtually every logistics vertical including CPG, Automotive, 3PL/4PL, Manufacturing, and International Freight Forwarding.

One of my most important tips for maximizing the effectiveness of your business logistics strategy is…

Focus on your competencies. Many companies think they need to “do it all” when it comes to logistics, but in reality there are many options available to organizations that are looking to develop effective and efficient logistics processes. Depending on the complexity of your reader’s shipping needs, for example, in some cases it may be easier to outsource logistics domestically to a 3PL or a global freight forwarder. And, even start ups that lack established IT departments can create effective logistics strategies by using an affordable SaaS-based transportation management solution (TMS). These platforms allow organizations to plan, execute and track freight without the concerns of managing software applications and computer hardware.

10 . come on focused on creating consumer-like business applications that make it simpler for businesses to run their company.

The best way to increase the effectiveness of your logistics plan is through…

Utilizing the technology available to you. My own company, Lettuce, has innovated a way for small business owners to cut costs by consolidating the entire sales, processing, accounting, inventory, forecasting, fulfillment and shipping process into the click of just one button – let that sink in a bit. It’s taken a task that spans across multiple departments and translated it into a single click.

Tools like this are what I think are essential for maximizing your logistic process. Lettuce is an inventory management program accessible via the web portal and iPad app, cuts out the middle man and eliminates repetitive data entry, saving businesses money by cutting overhead costs and brings in more profit by allowing salespeople to secure more sales because they’re not wasting time with back-end order processing. Not to mention it helps small companies go a little bit greener (like Lettuce) by replacing pen and paper, the traditional sales method, with an iPad. Companies can utilize this app to create instant digital catalogs, validate credit card info on the spot (perfect for trade shows), calculate shipping charges, sync with QuickBooks, forecast inventory needs and give wholesalers 24/7 access and ordering capability, slashing countless hours off the back-end fulfillment process.

11. When it comes to creating an effective, yet realistic, logistics strategy…

Plan to give the decision away.

I don’t mean that you have to use a 3PL or necessarily outsource your logistics in any way, but if you are an executive of your company, no matter how small, then make plans now to intentionally stay away from the logistics decision making. Smart executives hire smart managers to take care of inefficiencies in logistics and information flow, and then stay out of the way. Dumb logistics are sometimes the result of bad spreadsheets and bad logic, but that’s only a symptom of the disease. The real cause of dumb logistics is internal company politics. The “people with influence” want this or that, and the logistics get hammered. Spend your time making sure that your logistics managers, whether in-house or outsourced, are both (1) totally on-board with how logistics supports your strategy, and (2) totally empowered to make decisions without asking permission. You have bigger fish to fry.

12. 1 way to increase the effectiveness of your logistics strategy is to…

Have absolute clarity on the purpose of the logistics function in the organization. Investing in developing and clearly articulating the vision of logistics in support of the overall operation are foundational steps in defining optimum logistics strategies.

13.

When it comes to logistics planning and strategies…

Within the supply chain, there is the constant challenge to optimize service and cost performance. There are more tools and challenges than ever before; but at the end of the day, for supply chain professionals, it’s all about delivering low cost and great service. To accomplish this, companies need to gain end-to-end visibility of their network and analyze service and cost performance. It starts with building a solid transaction and information foundation. Often this means partnering with a third party logistics provider (3PL) who has the people, processes and technology needed to execute, gain visibility, track and report cost and service performance.

Secondly, companies need to make sure they have the right people planning, executing and optimizing their transportation network. Do you have a team of transportation professionals with a mix of real world experience and solid academic and analytical skills? Are they trained in Lean or Six Sigma? Can they communicate? Communication is critical across the supply chain – to internal stakeholders, customers, suppliers, carrier partners or others in the industry – and managing those relationships.

Once you have a solid base of information, you need to analyze the data then optimize their freight. There are two levels of optimization: strategic and tactical. Strategic optimization looks at procurement processes, mode selection and overall network design. Tactical optimization is considering if you’re using right carriers, if deliveries and pickups on-time, etc. Shippers need to analyze cost of service daily to see where they’re having carrier performance or other service issues.

The next step is reporting and continuous improvement. You’ve built that solid foundation of data accuracy and visibility and have the right team in place and made changes to optimize your freight; then it’s time to report track and seek continuous improvement. By creating executive dashboards and actionable reports, quarterly business reviews, and continuous ad-hoc reporting it’s possible to examine trends over time and how you’re trending versus a prior period.

Gaining visibility and leveraging the data can help companies identify opportunities to take cost and inefficiency out of their supply chain. Logistics should to be a resource to the entire company and help the organization meet its strategic objectives and drive value for shareholders and customers.

14 . the logistics transportation must be the best trained employees and arms them with brand new technology that combines vast operational experience with the latest advances in optimization and applied probability sciences.

The most important tip I can share with logistics professionals…

Would be to always remember your core competency. Focus on it. Ingrain it into your culture. Then, align your logistics strategy around that competency, and segment out your products, customers, and vendors.If your company is renowned for producing an industry-leading product, then focus on the innovation, quality and consistency that your customers expect. Your supply chain / logistics strategy should have a high-touch, value adding service component that keeps quality high.

If your product is commoditized and price is the only thing that differentiates you from your competitors, your supply chain / logistics strategy should focus on economies of scale and innovative ways to reduce waste.

Customers can then also be segmented by level of “importance” — focus on the ones that impact your business the most. These customers may or may not be the largest ones in your portfolio in terms of revenue. They may be middle of the pack customers who are collaborative and drive improvement in your business that can be replicated across other customers. Prioritizing these customers should be part of your logistics strategy.

Vendors can also be segmented by level of “importance” and again, it’s the collaborative ones — the ones that will work with you to improve your business and grow together — that you should include in your supply chain strategy.

Often times, start-up companies will try to differentiate themselves and win business by providing high levels of logistics service. If this is part of your strategy, then you know you have several options, from operating your own fleet to paying for premium service from an asset based or non-asset-based 3PL. This is why it is important to first understand your core competency. Are you a transportation company? Then yes, you should probably operate your own fleet. Do you make the best damn cupcakes in North America? Maybe you would consider outsourcing logistics…

Now, if you don’t want to be at the mercy of a logistics provider that treats you as the “little fish in a big pond,” one approach might be to seek a longer-term, contractually bound, collaborative relationship with a 3PL. By entrenching yourself into the 3PL’s business, a small or medium-sized start-up company encourages the logistics provider to invest in network development and build its capacity around the start-up company’s market. It’s the long-term commitment that builds stability for both the shipper and the carrier. With a strong collaborative relationship established, you can then work with the 3PL for additional value-adding and differentiating services down the road, such as custom software development, reporting and analytics, etc

15 . One of my most important tips for maximizing the effectiveness of your logistics strategy is…

Begin and end with customers and how they use your offerings! Logistics is about optimizing costs while providing outstanding service. And, not all customers are created equal! A segmented logistics strategy that considers the requirements of your most valuable customers first and designed accordingly wins! Business is about growing exceptional current results while building a strong base for the long term. Logistics is the capability that can orchestrate all of that to happen, by starting with an intimate understanding of product and service needs of every customer segment and linking them to the steps that provide breakthrough satisfaction to customers. Logistics is the external link between suppliers, production, customer interface, and results. It is the internal link between product development, marketing, sales, procurement, production, finance, and executive leadership. An effective logistics strategy will contribute to the financial health of the company and fuel its growth. When it starts with customer segment needs and expectations and understands the value you create for the customer, only then can it produce exhilarating customer response through delivery of knockout value.

16 . The truth about logistics strategy is that…

An effective logistics strategy at its core, is nothing more than the process of moving and positioning inventory to meet customer requirements at the lowest possible total cost to serve. For a business leader, it’s their responsibility to design and administer a system to control the flow and positioning of materials to support the business strategy. Every firm should adopt a strategic initiative to align suppliers and distributors into collaborative relationships to gain a competitive advantage. When this synchronization takes place, it’s called an integrated logistics model. There are a few key factors that comprise a successful integrated logistics model and they are: asset minimization, lowest total cost, and supply chain connectivity.

Since the business of logistics has become big business in the U.S., it’s also important to have a solid logistics structure in place. Critical components of a logistics structure that an organization should encompass are as follows: facility network, warehousing and material handling packaging, order management, transportation and inventory.

All of these things have one goal and that is to ensure customer success. No longer will excellent service and customer satisfaction lead to loyalty. For companies to now be competitive and successful, they will have to evolve their philosophy towards ensuring customer success. They will have to ask: “How can I enhance my customers’ performance?” This entails understanding customer requirements, processes and their total costs.

A successful logistics strategy will be a customer focused strategy. This will allow for a stronger franchise with best customers and lower logistics costs. It should also result in higher inventory turns and reduced expediting because you will be in a true partnership and not a tactical relationship with your customer base. The logistics value proposition for any company will focus on configuring in a customer relevant way while concurrently enhancing quality, productivity and operational excellence. Any successful strategy cannot remain static. Business leaders need to stay atop of technology and trends as they impact and change the scope of business faster than ever before.

17 . When it comes to logistics strategy success :

Employ an experienced transportation procurement specialist to vet and manage your vendors “in house”. Within these vendors, you want to work with a combination of asset based companies and at least 2 third-party logistics companies (3pl’s). 3pl companies have access to all modes of transportation throughout the entire market, and will be able to adapt to changes in the market throughout the year. Also, working with more than one of these companies will keep them in competition with one another and will usually net you the lowest price for their services.

18.

If I had one fundamental piece of logistics management advice for a company, it would be to…

Conduct a complete risk and resilience assessment prior to establishing a new supply chain. Unfortunately, resilience does not come in a box, and cannot be purchased just when you need it. While designing and building a resilient supply chain from the very beginning is much more cost-effective than trying to change the supply chain in mid-stream, many organizations must redesign them as they live with the results of one or more disasters or shocks.A resilient supply chain is one that is flexible in the face of disruptive events. For example, an inbound supply chain that uses Just-In-Time delivery of parts is lean and cost-effective in the short term, but may be easily disrupted by events beyond the control of its managers. Resilience means having the flexibility of being able to choose from multiple suppliers, several backup modes of transport, or keeping 24-48 hours of parts on hand to smooth out the parts flow during disruptive events. This type of built-in resilience can give operational managers the time to react should the event prove to be a longer-term disruption.

Although logistics systems are called supply chains, they are not linear chains as the name suggests. Rather, supply chains are very often complex webs or networks of infrastructure, suppliers, supplies and services. Managers can’t use linear thinking when determining the weaknesses and risks in a complex system. Therefore, using systems thinking to map and quantify the movement of goods and services, and the dependencies between the parts of the supply chain, is a much more effective way to identify risks in a modern logistics network. This map or model can then be used to demonstrate to company decision-makers where vulnerabilities exist, and by extension which parts of the network are at greatest risk.

Large firms with their own planning departments run scenarios to determine the most costly and the most vulnerable nodes in the network, and use the results of the scenarios to mitigate the risks ahead of time. Until now, smaller firms did not have that ability. However, new software tools are enabling small and medium-sized companies to run their own planning scenarios, and recover more quickly from known events.

Identifying vulnerabilities and mitigating the supply chain risks ahead of time is critical to your survival when the disruptive event hits. This extra time can mean the difference between collapse and the ability to save money, recover faster and with less impact on the business and, most importantly, its customers.

A resilient supply chain is the product of thorough analysis and careful planning. Tomorrow`s resilience is the product of the smart decisions made today. Risk discovery, risk analysis and risk mitigation are complex and potentially costly. Our company, RiskLogik, provides the skilled professionals, proven techniques and leading edge tools to help your company build resilience quickly and cost effectively. RiskLogik’s software is being used by the Government of Ontario to analyze and plan for critical infrastructure risk events, and also by the Government of New Brunswick to map supply chain risks and vulnerabilities within the province

19. “Today, freight transportation management is more than just about price. But how do shippers put together a transportation and supplier sourcing strategy that will…”

Earn them the capacity that they need at a price that works for all parties involved?

Tip: Consider Big Data

When asked to identify the trend with the greatest potential impact on the way procurement does it job over the next decade, the majority of the study participants chose predictive analytics or forecasting.

Analysts observe that as procurement’s role matures in transportation management from transactional facilitator to trusted business advisor, proficiency with the next generation of analytics—Big Data—will be a key enabler. Big Data may also add significant value when it comes to customer analytics, bringing more agility to model massive volumes of structured and unstructured data from multiple sources.

20.transportation management provides that delivers engineering, technology, and sustainability solutions to a customer base of established global organizations. a consultative approach with some of the largest high tech and telecom companies around the world and helps them meet objectives in improved customer service, efficiency gains, increased market penetration, and revenue growth. also focuses on managing customer solutions inclusive of supply chain deign, business process re-engineering, and technology solutions.

“There’s no doubt that supply chain and logistics issues are critical to any company’s success. But dramatic improvements don’t always involve…”

Large-scale strategic overhauls or process changes that require months to implement.

Small parcel carriers can often provide a cost savings on multi-piece shipments that don’t involve a full pallet or multiple pallets. Look at small parcel vs. LTL carrier or LTL vs. truckloads to understand the price differentials for various weight and zone break points. Changing the routing or mode of shipments can pay off, especially for midmarket shippers.

Make sure your A and B movers are properly located to allow for minimum processing time and distance to the outbound shipping lanes. Place those fast movers carefully. If they are all in the same aisle or location, you can create a bottleneck as employees run into each other doing the pick.

Companies shipping from more than one location would want A & B movers in each, but D movers in just one, to keep inventory carrying costs down. If you decide you need to have 100 D movers, put them where the warehouse space and labor costs are lowest. That can reduce your inbound shipping cost, too.

21.

… the companies that are the most customer-centric have ten characteristics:

- Clarity of purpose for the buyer

- Take ownership of the channel: drive reliability and excitement

- Build segmented customer strategies: tie strategy to policy/execution

- Cost-to-serve with data-driven discussions

- The supply chain has a clear focus on outcomes

- Alignment between operations and commercial teams

- Build outside-in processes

- Hands-free and reliable order processes

- Cross-functional listening

- Execute at the moments of truth

22. “What we find is that the better aligned your strategies are – from supply chain to transportation to carrier strategies – and the better aligned they are with execution, the better able and more effective you are at…”

Managing both cost and service at the same time. Being able to benchmark allows you to identify your supply chain performance and the positioning of your supply chain within the business – both critical factors in determining what kind of shipper you are.

[The key to enabling alignment and synchronization across a broader supply chain strategy is] the people, process, and technology that allow you to hook everything together and make sure there’s alignment over time. Processes and technologies that are designed to provide transparency, visibility, and data are critical to ensuring an alignment between the various levels of strategy. We talk about a waterfall from the carrier to the supply chain strategy to the transportation strategy to the carrier strategy and then to the execution. There’s also a feedback loop forward that allows you to understand whether your strategies are aligned, and what impact changes have on your overall performance. An example would be, what is your carrier performance telling you about your supply chain strategy? If you have a significant change in your on-time or cost performance, what is that telling you about your supply chain strategy? Having that feedback loop ensures alignment.

XXX . V0 Example Products for efficient transportation & logistics

TRANSPOREON is a web-based logistics platform that links industrial and commercial companies with their logistics service providers. It allows cost-saving, transparent online handling of all workflows related to the transportation management process. The Transporeon product portfolio includes automated shipment execution, dock scheduling, visibility, reporting and much more. More than 1000 shippers and over 57,000 carriers currently benefit from TRANSPOREON's solutions.

Live demo for prospects (industry & trade)

Request a free live demo session with our experts to see our innovative software solutions in action.

Learn how the TRANSPOREON Cloud will drive efficiencies into your logistics and supply chain processes.

Shipment execution

Automated, flexible shipment processing - The TRANSPOREON Way

Companies can use TRANSPOREON shipment execution to assign transport orders to carriers. Conversely, carriers have the ability to provide their shipping customers with the suitable product offer. Through electronic assignment, both parties save freight, process and telephone costs and improve their delivery quality. Using TRANSPOREON, companies benefit from various options of shipment execution, adapted to individual needs and cost-effective basic conditions.

Dock scheduling

Control your docks. Eliminate detention charges.

Book time slots online, arrive, load/unload on-time and be back on the road quickly – this is how TRANSPOREON dock scheduling works. Dock scheduling ensures less idle time during loading and unloading, equalizes peak times and reduces waiting time. Shippers can provide their goods in a timely manner and use their shipping team to their optimal capacity.

Visibility

"Where are my goods?" Track reliably using shipment tracking

TRANSPOREON visibility brings more transparency to your transportation process. By means of status messages, all goods can be tracked: From pickup to delivery to the end customer. Delays are reported immediately, even before the customer asks. Each step is documented. Carriers use this information as proof of delivery; shippers use it as a performance measurement or supplier evaluation.

Reporting

Optimize company performance through reliable key performance indicators

Using the reporting module from TRANSPOREON , important key performance indicators can be determined easily and evaluations can be created at any time at the press of a button. Thus, all relevant information is up-to-date and available quickly. For example, on the performance of the transport company, adherence to deadlines, scheduling quotas or the ratio of supply and demand.

XXX . V00 Transportation Economics/Costs

Costs

Introduction

Price, cost and investment issues in transportation garner intense interest. This is certainly to be expected from a sector that has been subject to continued public intervention since the ninteenth century. While arguments of market failure, where the private sector would not provide the socially optimal amount of transportation service, have previously been used to justify the economic regulations which characterized the airline, bus, trucking, and rail industries, it is now generally agreed, and supported by empirical evidence, that the move to a deregulated system, in which the structure and conduct of the different modes are a result of the interplay of market forces occurring within and between modes, will result in greater efficiency and service.

Many factors have led to a reexamination of where, and in which mode, transportation investments should take place. First, and perhaps most importantly, is the general move to place traditional government activities in a market setting. The privatization and corporatization of roadways and parts of the aviation systems are good examples of this phenomenon. Second, there is now a continual and increasing fiscal pressure exerted on all parts of the economy as the nation reduces the proportion of the economy’s resources which are appropriated by government. Third, there is increasing pressure to fully reflect the environmental, noise, congestion, and safety costs in prices paid by transportation system users. Finally, there is an avid interest in the prospect of new modes like high speed rail (HSR) to relieve airport congestion and improve in environmental quality. Such a major investment decision ought not be made without understanding the full cost implications of a technology or investment compared to alternatives.

This chapter introduces cost concepts, and evidence on internal costs. The chapter on Negative externalities reviews external costs.

Supply

In imperfectly competitive markets, there is no one-to-one relation between P and Q supplied, i.e., no supply curve. Each firm makes supply quantity decision which maximises profit, taking into account the nature of competition (more on this in pricing section).

Supply function (curve). specifies the relationship between price and output supplied in the market. In a perfectly competitive market, the supply curve is well defined. Much of the work in transportation supply does not estimate Supply-curve. Instead, focus is on studying behaviour of the aggregate costs (in relation to outputs) and to devising the procedure for estimating costs for specific services (or traffic). Transport economists normally call the former as aggregate costing and the latter as disaggregate costing. For aggregate costing, all of the cost concepts developed in micro-economics can be directly applied.

Types of Costs

There are many types of costs. Key terms and brief definitions are below.

- Fixed costs (): The costs which do not vary with output.

- Variable costs (): The costs which change as output levels are changed. The classification of costs as variable or fixed is a function of both the length of the time horizon and the extent of indivisibility over the range of output considered.

- Total costs (): Total expenditures required to achieve a given level of output ().

- Total costs = fixed costs + variable costs. = a + bQ

- Average costs: The total cost divided by the level of output.

- Average Cost for a single product firm: ,

- Average fixed cost =

- Average variable cost =

- Average Cost for a multi-product firm is not obvious (i.e. which output), two methods

- Ray average cost: Fix the output proportion and then examine how costs change as the scale of output is increased along the output 'ray'. Like moving out along a ray in output space - thus 'ray' average cost; multiproduct scale economies exists if there is DRAC (declining ray average cost). (Fixity or Variability depends on the time horizon of the decision problem and is closely related to the indivisibility of production (costs).)

- Incremental average cost: Fix all other output except one, and then examine the incremental cost of producing more ith output - thus, incremental average cost; product-specific scale economies exist if there is DAIC (declining average incremental cost).

- Average Cost for a single product firm: ,

- Marginal (or incremental) cost: The derivative (difference) of Total Cost with respect to a change in output.

- Marginal Cost MC =

- Incremental Cost IC =

- Opportunity costs: The actual opportunities forgone as a consequence of doing one thing as opposed to another. Opportunity cost represents true economics costs, and thus, must be used in all cases.

- Social cost: The cost the society incurs when its resources are used to produce a given commodity, taking into account the external costs and benefits.

- Private cost: The cost a producer incurs in getting the resources used in production.

The production of transport services in most modes involves joint and common costs. A joint cost occurs when the production of one good inevitably results in the production of another good in some fixed proportion. For example, consider a rail line running only from point A to point B. The movement of a train from A to B will result in a return movement from B to A. Since the trip from A to B inevitably results in the costs of the return trip, joint costs arise. Some of the costs are not traceable to the production of a specific trip, so it is not possible to fully allocate all costs nor to identify separate marginal costs for each of the joint products. For example, it is not possible to identify a marginal cost for an i to j trip and a separate marginal cost for a j to i trip. Only the marginal cost of the round trip, what is produced, is identifiable.

Common costs arise when the facilities used to produce one transport service are also used to produce other transport services (e.g. when track or terminals used to produce freight services are also used for passenger services). The production of a unit of freight transportation does not, however, automatically lead to the production of passenger services. Thus, unlike joint costs, the use of transport facilities to produce one good does not inevitably lead to the production of some other transport service since output proportions can be varied. The question arises whether or not the presence of joint and common costs will prevent the market mechanism from generating efficient prices. Substantial literature in transport economics (Mohring, 1976; Button, 1982; Kahn, 1970) has clearly shown that conditions of joint, common or non-allocable costs will not preclude economically efficient pricing.

- Traceable cost (untraceable cost): A cost which can (cannot) be directly assigned to a particular output (service) on a cause-and-effect basis. Traceable (untraceable) costs may be fixed or variable (or indivisible variable). Traceability is associated with production of more than one output, while untraceable costs possess either (or both) common costs and joint costs. The ability to identify costs with an aggregate measure of output supplied (e.g. the costs of a round trip journey) does not imply that the costs are traceable to specific services provided.

- Joint cost: A cost which is incurred simultaneously during the production for two or more products, where it is not possible to separate the contributions between beneficiaries. These may be fixed or variable (e.g. cow hides and cow steaks).

- Common cost: A cost which is incurred simultaneously for a whole organization, where it cannot be allocated directly to any particular product. These may be fixed or variable (e.g. the farm's driveway).

External and Internal Costs

External costs are discussed more in Negative externalitiesEconomics has a long tradition of distinguishing those costs which are fully internalized by economic agents (internal or private costs) and those which are not (external or social costs). The difference comes from the way that economics views the series of interrelated markets. Agents (individuals, households, firms and governments) in these markets interact by buying and selling goods are services, as inputs to and outputs from production. A firm pays an individual for labor services performed and that individual pays the grocery store for the food purchased and the grocery store pays the utility for the electricity and heat it uses in the store. Through these market transactions, the cost of providing the good or service in each case is reflected in the price which one agent pays to another. As long as these prices reflect all costs, markets will provide the required, desirable, and economically efficient amount of the good or service in question.

The interaction of economic agents, the costs and benefits they convey or impose on one another are fully reflected in the prices which are charged. However, when the actions of one economic agent alter the environment of another economic agent, there is an externality. An action by which one consumers purchase changes the prices paid by another is dubbed a pecuniary externality and is not analyzed here further; rather it is the non-pecuniary externalities with which we are concerned. More formally, "an externality refers to a commodity bundle that is supplied by an economic agent to another economic agent in the absence of any related economic transaction between the agents" (Spulber, 1989). [1] Note that this definition requires that there not be any transaction or negotiation between either of the two agents. The essential distinction which is made is harm committed between strangers which is an external cost and harm committed between parties in an economic transaction which is an internal cost. A factory which emits smoke forcing nearby residents to clean their clothes, cars and windows more often, and using real resources to do so, is generating an externality or, if we return to our example above, the grocery store is generating an externality if it generates a lot of garbage in the surrounding area, forcing nearby residents to spend time and money cleaning their yards and street.

There are alternative solutions proposed for the mitigation of these externalities. One is to use pricing to internalize the externalities; that is, including the cost which the externalities impose in the price of the product/service which generate them. If in fact the store charged its customers a fee and this fee was used to pay for the cleanup we can say the externality of ‘unsightly garbage’ has been internalized. Closer to our research focus, an automobile user inflicts a pollution externality on others when the car emits smoke and noxious gases from its tailpipe, or a jet aircraft generates a noise externality as it flies its landing approach over communities near the airport. However, without property rights to the commodities of clean air or quiet, it is difficult to imagine the formation of markets. The individual demand for commodities is not clearly defined unless commodities are owned and have transferable property rights. It is generally argued that property rights will arise when it is economic for those affected by externalities to internalize the externalities. These two issues are important elements to this research since the implicit assumption is that pricing any of the externalities is desirable. Secondly, we assume that the property rights for clean air, safety and quiet rest with the community not auto, rail and air users. Finally, we are assuming that pricing, meaning the exchange of property rights, is possible. These issues are considered in greater detail in Chapter 3 where the broad range of estimates for the costs of the externalities are considered.

Other terms

- Sunk costs: These are costs that were incurred in the past. Sunk costs are irrelevant for decisions, because they cannot be changed.

- Indivisible costs: Do not vary continuously with different levels of output or must expenditures, but be made in discrete "lumps". Indivisible costs are usually variable for larger but not for smaller changes in output

- Escapable costs (or Avoidable costs): A cost which can be avoided by curtailing production. There are both escapable fixed costs and escapable variable costs. The escapability of costs depends on the time horizon and indivisibility of the costs, and on the opportunity costs of assets in question.

Time Horizon

Once having established the cost function it must be developed in a way which makes it amenable to decision-making. First, it is important to consider the length of the planning horizon and how many degrees of freedom we have. For example, a trucking firm facing a new rail subsidy policy will operate on different variables in the short run or a period in which it cannot adjust all of its decision variables than it would over the long run, the period over which it can adjust everything.Long run costs, using the standard economic definition, are all variable; there are no fixed costs. However, in the short run, the ability to vary costs in response to changing output levels and mixes differs among the various modes of transportation. Since some inputs are fixed, short run average cost is likely to continue to fall as more output is produced until full capacity utilization is reached. Another potential source of cost economies in transportation are economies of traffic density; unit cost per passenger-kilometer decreases as traffic flows increase over a fixed network. Density economies are a result of using a network more efficiently. The potential for density economies will depend upon the configuration of the network. Carriers in some modes, such as air, have reorganized their network, in part, to realize these economies.

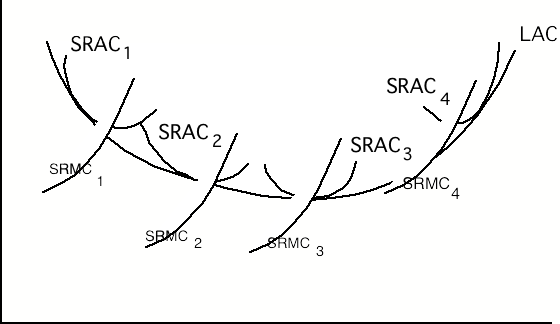

In the long run, additional investment is needed to increase capacity and/or other fixed inputs. The long run average cost curve, however, is formed by the envelope of the short run average cost curves. For some industries, the long run average cost often decreases over a broad range of output as firm size (both output and capacity) expands. This is called economies of scale. The presence of economies at the relevant range of firm size means that the larger the size of the firm, the lower the per-unit cost of output. These economies of scale may potentially take a variety of forms in transportation services and may be thought to vary significantly according to the mode of transportation involved.

Time horizon in economic theory

- Short run: the period of time in which the input of one or more productive agents is fixed

- Long run: the period of time in which all inputs are variable

- the type of decision: when do the costs and benefits occur ?

- the expected life time of assets involved

- the time horizon for major transportation projects tends to be lengthy relative to that in other industries

In the diagram below the relationship between average and marginal costs for four different firm sizes is illustrated. Note that this set of cost curves was generated from a non-homogeneous production function. You will note that the long run average cost function (LAC) is U-shaped thereby exhibiting all dimensions of scale economies.

Mathematically

where: provides the optimal plant size.

Indicators of Aggregate Cost Behavior

Scale economies is the behavior of costs when the AMOUNT of an output increases while scope economies refers to the changes in costs when the NUMBER of outputs increases.Economies of Scale

Economies of scale refer to a long run average cost curve which slopes down as the size of the transport firm increases. The presence of economies of scale means that as the size of the transport firm gets larger, the average or unit cost gets smaller. Since most industries have variable returns to scale cost characteristics, whether or not a particular firm enjoys increasing, constant or decreasing returns to scale depends on the overall market size and the organization of the industry.The presence or absence of scale economies is important for the industrial structure of the mode. If there were significant scale economies, it would imply fewer larger carriers would be more efficient and this, under competitive market circumstances, would naturally evolve over time. Scale economies are important for pricing purposes since the greater are the scale economies, the more do average and marginal costs deviate. It would, therefore, be impossible to avoid a deficit from long run marginal [social] cost pricing.

Another note of terminology should be mentioned. Economics of scale is a cost concept, returns to scale is a related idea but refers to production, and the quantity of inputs needed. If we double all inputs, and more than double outputs, we have increasing returns to scale. If we have less than twice the number of outputs, we have decreasing returns to scale. If we get exactly twice the output, then there are constant returns to scale. In this study, since we are referring to costs, we use economies of scale. The presence of economies of scale does not imply the presence of returns to scale.

Scale measures long-run (fully adjusted) relationship between average cost and output. Since a firm can change its size (network and capacity) in the long run, Economies of Scale (EoS) measures the relationship between average cost and firm size. EoS can be measured from an estimated aggregate cost function by computing the elasticity of total cost with respect to output and firm size (network size for the case of a transport firm).

Returns to Scale (Output Measure)

Increasing Returns to Scale (RtS)Decreasing RtS

Economies of Scale (Cost Measure)

Economies of scale (EoS) represent the behavior of costs with a change in output when all factors are allowed to vary. Scale economies is clearly a long run concept. The production function equivalent is returns to scale. If cost increase less than proportionately with output, the cost function is said to exhibit economies of scale, if costs and output increase in the same proportion, there are said to be 'constant returns to scale' and if costs increase more than proportionately with output, there are diseconomies of scale.- if cost elasticity < 1, or -> increasing EoS

- if cost elasticity = 1, or -> constant EoS

- if cost elasticity > 1, or -> decreasing EoS

Economies of Density

There has been some confusion in the literature between economies of scale and economies of density. These two distinct concepts have been erroneously used interchangeably in a number of studies where the purpose was to determine whether or not a particular mode of transportation (the railway mode has been the subject of considerable attention) is characterized by increasing economies or diseconomies of scale. There is a distinction between density and scale economies. Density economies are said to exist when a one percent increase in all outputs, holding network size, production technology, and input prices constant, increase the firm’s cost by less than one percent. In contrast, scale economies exist when a one percent increase in output and size of network increases the cost by less than one percent, with production technology and input prices held constant.Economies of density, although they have a different basis than scale economies, can also contribute to the shape of the modal industry structure. It can affect the way a carrier will organize the delivery of its service spatially. The presence of density economies can affect the introduction of efficient pricing in the short term, but generally not over the long term since at some point density economies will be exhausted. This, however, will depend upon the size of the market. In the air market, for example, deregulation has allowed carriers to respond to market forces and obtain the available density economies to varying degrees.

Returns to Density similar to returns to a capacity utilization when capacity is fixed in the short run. Since the plant size (network size for the case of transportation firms) is largely fixed in the short run, RTD measures the behavior of cost when increasing traffic level (output) given the plant size (network size). It is measured by the cost elasticity with respect to output.

- if cost elasticity < 1, or -> increasing EoD

- if cost elasticity = 1, or -> constant EoD

- if cost elasticity > 1, or -> decreasing EoD

Economies of Capacity Utilization

A subtle distinction exists between economies of density, which is a spatial concept, and economies of capacity utilization, which may be aspatial. As a fixed capacity is used more intensively, the fixed cost can be spread over more units or output, and we have declining average cost, economies of scale. However, as the capacity is approached, costs may rise as delays occur. This gives a u-shaped cost curve.While economies of scale refer to declining average costs, for whatever reason, when output increases; and economies of density refer to declining costs when output increases and the network mileage is held constant; economies of capacity utilization refers to declining costs as the percentage of capacity which is used increases, where capacity may be spatial or aspatial.

While density refers to how much space is occupied, capacity refers to how much a capacitated server (e.g. a bottleneck, the number of seats on a plane) is occupied, and may incorporate economies of density if the link is capacitated, such as a congesting roadway. However if a link has unlimited (or virtually unlimited) capacity, such as intercity passenger trains on a dedicated right-of-way at low levels of traffic, then economy of density is a more appropriate concept. Another way of viewing the difference is that economies of density refers to linear miles, while economies of utilization refer to lane miles.

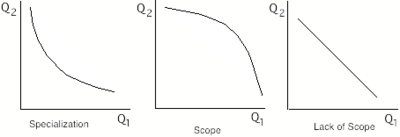

Economies of Scope