Fund turnover and intelligence observation are inversely proportional to economic resources such as natural resources, human resources (labor), because the circulation of funds and intelligence observations must be 100 percent automatic without human intervention, if natural resources and labor resources are already certainly 100 percent manual, so we need an electronic turbo sequence engine as a source of energy as well as a source of control of spacecraft and aircraft traffic control outside the earth such as the latest USA army division.

EINSTEIN to AMNIMARJESLOW and RUTHERFORD

( Gen. Mac Tech Zone Fund turnover and intelligence )

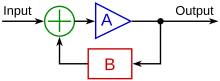

Fundamentally, there are two types of control loops: open loop control and closed loop (feedback) control. In open loop control, the control action from the controller is independent of the "process output" (or "controlled process variable" - PV).

In this earth we need a defense of the defense system on earth and above the earth, like the world of intelligence that is precise and certain. several theories and practices that are possible in this review are needed discussion of how to translate human logic into electronic logic and mathematical logic analysis of physics and chemistry for example:

1. AND circuit = AND gates

2. OR circuit = OR gates

3. NOT circuit = Inverter gates

4. Encoder and Decoder

5. Ex-OR gates

6. Multiplexers

7. Three state buffer

8. Counter

9. register

10. Shift Register

11. Storage program

12. sequence control

13. IC and CHIP as an electronic control circuit

14. Bus, signal, interuption, set and reset, request, exchange to be

read and write control

15. Measurement and adjustment of a variable that controls an

individual process.

Control flow

In computer science, control flow (or flow of control) is the order in which individual statements, instructions or function calls of an imperative program are executed or evaluated. The emphasis on explicit control flow distinguishes an imperative programming language from a declarative programming language.Within an imperative programming language, a control flow statement is a statement, the execution of which results in a choice being made as to which of two or more paths to follow. For non-strict functional languages, functions and language constructs exist to achieve the same result, but they are usually not termed control flow statements.

A set of statements is in turn generally structured as a block, which in addition to grouping, also defines a lexical scope.

Interrupts and signals are low-level mechanisms that can alter the flow of control in a way similar to a subroutine, but usually occur as a response to some external stimulus or event (that can occur asynchronously), rather than execution of an in-line control flow statement.

At the level of machine language or assembly language, control flow instructions usually work by altering the program counter. For some central processing units (CPUs), the only control flow instructions available are conditional or unconditional branch instructions, also termed jumps.

Control system

A control system manages, commands, directs, or regulates the behavior of other devices or systems using control loops. It can range from a single home heating controller using a thermostat controlling a domestic boiler to large Industrial control systems which are used for controlling processes or machines.For continuously modulated control, a feedback controller is used to automatically control a process or operation. The control system compares the value or status of the process variable (PV) being controlled with the desired value or setpoint (SP), and applies the difference as a control signal to bring the process variable output of the plant to the same value as the setpoint.

For sequential and combinational logic, software logic, such as in a programmable logic controller, is used.

The centrifugal governor is an early proportional control mechanism.

Open-loop and closed-loop control

There are two common classes of control action: open loop and closed loop. In an open-loop control system, the control action from the controller is independent of the process variable. An example of this is a central heating boiler controlled only by a timer. The control action is the switching on or off of the boiler. The process variable is the building temperature.This controller operates the heating system for a constant time regardless of the temperature of the building.In a closed-loop control system, the control action from the controller is dependent on the desired and actual process variable. In the case of the boiler analogy, this would utilize a thermostat to monitor the building temperature, and feed back a signal to ensure the controller output maintains the building temperature close to that set on the thermostat. A closed loop controller has a feedback loop which ensures the controller exerts a control action to control a process variable at the same value as the setpoint. For this reason, closed-loop controllers are also called feedback controllers.

Feedback control systems

Example of a single industrial control loop; showing continuously modulated control of process flow.

A basic feedback loop

Control systems that include some sensing of the results they are trying to achieve are making use of feedback and can adapt to varying circumstances to some extent. Open-loop control systems do not make use of feedback, and run only in pre-arranged ways.

Logic control

Logic control systems for industrial and commercial machinery were historically implemented by interconnected electrical relays and cam timers using ladder logic. Today, most such systems are constructed with microcontrollers or more specialized programmable logic controllers (PLCs). The notation of ladder logic is still in use as a programming method for PLCs.Logic controllers may respond to switches and sensors, and can cause the machinery to start and stop various operations through the use of actuators. Logic controllers are used to sequence mechanical operations in many applications. Examples include elevators, washing machines and other systems with interrelated operations. An automatic sequential control system may trigger a series of mechanical actuators in the correct sequence to perform a task. For example, various electric and pneumatic transducers may fold and glue a cardboard box, fill it with product and then seal it in an automatic packaging machine.

PLC software can be written in many different ways – ladder diagrams, SFC (sequential function charts) or statement lists.

On–off control

On–off control uses a feedback controller that switches abruptly between two states. A simple bi-metallic domestic thermostat can be described as an on-off controller. When the temperature in the room (PV) goes below the user setting (SP), the heater is switched on. Another example is a pressure switch on an air compressor. When the pressure (PV) drops below the setpoint (SP) the compressor is powered. Refrigerators and vacuum pumps contain similar mechanisms. Simple on–off control systems like these can be cheap and effective.Linear control

Linear control systems use negative feedback to produce a control signal to maintain the controlled PV at the desired SP. There are several types of linear control systems with different capabilities.Proportional control

Step responses for a second order system defined by the transfer function , where is the damping ratio and is the undamped natural frequency.

The proportional control system is more complex than an on–off control system, but simpler than a proportional-integral-derivative (PID) control system used, for instance, in an automobile cruise control. On–off control will work for systems that do not require high accuracy or responsiveness, but is not effective for rapid and timely corrections and responses. Proportional control overcomes this by modulating the manipulated variable (MV), such as a control valve, at a gain level which avoids instability, but applies correction as fast as practicable by applying the optimum quantity of proportional correction.

A drawback of proportional control is that it cannot eliminate the residual SP–PV error, as it requires an error to generate a proportional output. A PI controller can be used to overcome this. The PI controller uses a proportional term (P) to remove the gross error, and an integral term (I) to eliminate the residual offset error by integrating the error over time.

In some systems there are practical limits to the range of the MV. For example, a heater has a limit to how much heat it can produce and a valve can open only so far. Adjustments to the gain simultaneously alter the range of error values over which the MV is between these limits. The width of this range, in units of the error variable and therefore of the PV, is called the proportional band (PB).

Furnace example

When controlling the temperature of an industrial furnace, it is usually better to control the opening of the fuel valve in proportion to the current needs of the furnace. This helps avoid thermal shocks and applies heat more effectively.At low gains, only a small corrective action is applied when errors are detected. The system may be safe and stable, but may be sluggish in response to changing conditions. Errors will remain uncorrected for relatively long periods of time and the system is over damped. If the proportional gain is increased, such systems become more responsive and errors are dealt with more quickly. There is an optimal value for the gain setting when the overall system is said to be critically damped. Increases in loop gain beyond this point lead to oscillations in the PV and such a system is under damped.

Underdamped

In the furnace example, suppose the temperature is increasing towards a setpoint. Once the setpoint is reached, stored heat within the heater sub-system and in the walls of the furnace will keep the measured temperature rising beyond what is required. After rising above the set point, the temperature falls back and eventually heat is applied again. Now the heater and the furnace walls cool and the temperature falls too low before its fall is arrested and the cycle repeats.The temperature oscillations that an under damped furnace control system produces are unacceptable for many reasons, including the waste of fuel and time (each oscillation cycle may take many minutes), as well as the likelihood of seriously overheating both the furnace and its contents.

Overdamped

Suppose that the gain of the control system is reduced drastically and it is restarted. As the temperature approaches, say 30° below SP (A 60° proportional band (PB) this time), the heat input begins to be reduced, the rate of heating of the furnace has time to slow and, as the heat is still further reduced, it eventually is brought up to set point, just as 50% power input is reached and the furnace is operating as required. There was some wasted time while the furnace crept to its final temperature using only 52% then 51% of available power, but at least no harm was done. By carefully increasing the gain (i.e. reducing the width of the PB) this over damped and sluggish behavior can be improved until the system is critically damped for this SP temperature. Doing this is known as 'tuning' the control system. A well-tuned proportional furnace temperature control system will usually be more effective than on-off control, but will still respond more slowly than the furnace could under skillful manual control.PID control

A block diagram of a PID controller

Effects of varying PID parameters (Kp,Ki,Kd) on the step response of a system.

To resolve these two problems, many feedback control schemes include mathematical extensions to improve performance. The most common extensions lead to proportional-integral-derivative control, or PID control.

Derivative action

The derivative part is concerned with the rate-of-change of the error with time: If the measured variable approaches the setpoint rapidly, then the actuator is backed off early to allow it to coast to the required level; conversely if the measured value begins to move rapidly away from the setpoint, extra effort is applied—in proportion to that rapidity—to try to maintain it.Derivative action makes a control system behave much more intelligently. On control systems like the tuning of the temperature of a furnace, or perhaps the motion-control of a heavy item like a gun or camera on a moving vehicle, the derivative action of a well-tuned PID controller can allow it to reach and maintain a setpoint better than most skilled human operators could.

If derivative action is over-applied, it can lead to oscillations too. An example would be a PV that increased rapidly towards SP, then halted early and seemed to "shy away" from the setpoint before rising towards it again.

Integral action

Change of response of second order system to a step input for varying Ki values.

Ramp up % per minute

Some controllers include the option to limit the "ramp up % per minute". This option can be very helpful in stabilizing small boilers (3 MBTUH), especially during the summer, during light loads. A utility boiler "unit may be required to change load at a rate of as much as 5% per minute (IEA Coal Online - 2, 2007)".Other techniques

It is possible to filter the PV or error signal. Doing so can reduce the response of the system to undesirable frequencies, to help reduce instability or oscillations. Some feedback systems will oscillate at just one frequency. By filtering out that frequency, more "stiff" feedback can be applied, making the system more responsive without shaking itself apart.Feedback systems can be combined. In cascade control, one control loop applies control algorithms to a measured variable against a setpoint, but then provides a varying setpoint to another control loop rather than affecting process variables directly. If a system has several different measured variables to be controlled, separate control systems will be present for each of them.

Control engineering in many applications produces control systems that are more complex than PID control. Examples of such fields include fly-by-wire aircraft control systems, chemical plants, and oil refineries. Model predictive control systems are designed using specialized computer-aided-design software and empirical mathematical models of the system to be controlled.

Hybrid systems of PID and logic control are widely used. The output from a linear controller may be interlocked by logic for instance.

Fuzzy logic

Fuzzy logic is an attempt to apply the easy design of logic controllers to the control of complex continuously varying systems. Basically, a measurement in a fuzzy logic system can be partly true, that is if yes is 1 and no is 0, a fuzzy measurement can be between 0 and 1.The rules of the system are written in natural language and translated into fuzzy logic. For example, the design for a furnace would start with: "If the temperature is too high, reduce the fuel to the furnace. If the temperature is too low, increase the fuel to the furnace."

Measurements from the real world (such as the temperature of a furnace) are converted to values between 0 and 1 by seeing where they fall on a triangle. Usually, the tip of the triangle is the maximum possible value which translates to 1.

Fuzzy logic, then, modifies Boolean logic to be arithmetical. Usually the "not" operation is "output = 1 - input," the "and" operation is "output = input.1 multiplied by input.2," and "or" is "output = 1 - ((1 - input.1) multiplied by (1 - input.2))". This reduces to Boolean arithmetic if values are restricted to 0 and 1, instead of allowed to range in the unit interval [0,1].

The last step is to "defuzzify" an output. Basically, the fuzzy calculations make a value between zero and one. That number is used to select a value on a line whose slope and height converts the fuzzy value to a real-world output number. The number then controls real machinery.

If the triangles are defined correctly and rules are right the result can be a good control system.

When a robust fuzzy design is reduced into a single, quick calculation, it begins to resemble a conventional feedback loop solution and it might appear that the fuzzy design was unnecessary. However, the fuzzy logic paradigm may provide scalability for large control systems where conventional methods become unwieldy or costly to derive.

Fuzzy electronics is an electronic technology that uses fuzzy logic instead of the two-value logic more commonly used in digital electronics.

Physical implementation

A

DCS control room where plant information and controls are displayed on

computer graphics screens. The operators are seated as they can view and

control any part of the process from their screens, whilst retaining a

plant overview.

A control panel of a hydraulic heat press machine with dedicated software for that function

Logic systems and feedback controllers are usually implemented with programmable logic controllers.

Behavior tree (artificial intelligence, robotics and control)

A Behavior Tree is a mathematical model of plan execution used in computer science, robotics, control systems and video games.

They describe switchings between a finite set of tasks in a modular

fashion. Their strength comes from their ability to create very complex

tasks composed of simple tasks, without worrying how the simple tasks

are implemented. Behavior trees present some similarities to hierarchical state machines

with the key difference that the main building block of a behavior is a

task rather than a state. Its ease of human understanding make behavior

trees less error prone and very popular in the game developer

community. Behavior trees have been shown to generalize several other

control architectures

Behavior tree modelling the search and grasp plan of a two-armed robot

Background

Behavior trees originate from the computer game industry as a powerful tool to model the behavior of non-player characters (NPCs). They have been extensively used in high-profile video games such as Halo, Bioshock, and Spore. Recent works propose behavior trees as a multi-mission control framework for UAV, complex robots, robotic manipulation, and multi-robot systems. Behavior trees have now reached the maturity to be treated in Game AI textbooks as well as generic game environments such as PyGame and Unreal Engine (see links below).Key concepts

A behavior tree is graphically represented as a directed tree in which the nodes are classified as root, control flow nodes, or execution nodes (tasks). For each pair of connected nodes the outgoing node is called parent and the incoming node is called child. The root has no parents and exactly one child, the control flow nodes have one parent and at least one child, and the execution nodes have one parent and no children. Graphically, the children of a control flow node are placed below it, ordered from left to right.The execution of a behavior tree starts from the root which sends ticks with a certain frequency to its child. A tick is an enabling signal that allows the execution of a child. When the execution of a node in the behavior tree is allowed, it returns to the parent a status running if its execution has not finished yet, success if it has achieved its goal, or failure otherwise.

Control flow node

A control flow node is used to control the subtasks of which it is composed. A control flow node may be either a selector (fallback) node or a sequence node. They run each of their subtasks in turn. When a subtask is completed and returns its status (success or failure), the control flow node decides whether to execute the next subtask or not.Selector (fallback) node

Figure I. Graphical representation of a fallback composition of N tasks.

In pseudocode, the algorithm for a fallback composition is:

1 for i from 1 to n do

2 childstatus ← Tick(child(i))

3 if childstatus = running

4 return running

5 else if childstatus = success

6 return success

7 end

8 return failure

Sequence node

Figure II. Graphical representation of a sequence composition of N tasks.

In pseudocode, the algorithm for a sequence composition is:

1 for i from 1 to n do

2 childstatus ← Tick(child(i))

3 if childstatus = running

4 return running

5 else if childstatus = failure

6 return failure

7 end

8 return success

Mathematical state space definition

In order to apply control theory tools to the analysis of behavior trees, they can be defined as three-tuple.where is the index of the tree, is a vector field representing the right hand side of an ordinary difference equation, is a time step and is the return status, that can be equal to either Running , Success , or Failure .

Note: A task is degenerate behavior tree with no parent and no child.

Behavior tree execution

The execution of a behavior tree is described by the following standard ordinary difference equations:where represent the discrete time, and is the state space of the system modelled by the behavior tree.

Fallback composition

Two behavior trees and can be composed into a more complex behavior tree using a Fallback operator.Then return status and the vector field associated with are defined (for ) as follows:

Sequence composition

Two behavior trees and can be composed into a more complex behavior tree using a Sequence operator.Then return status and the vector field associated with are defined (for ) as follows:

A closed loop control system is a set of mechanical or electronic

devices that automatically regulates a process variable to a desired

state or set point without human interaction. Closed loop control

systems contrast with open loop control systems, which require manual

input.

closed loop control system

A closed loop control system is a set of mechanical or electronic devices that automatically regulates a process variable to a desired state or set point without human interaction. Closed loop control systems contrast with open loop control systems, which require manual input.

A control loop is the system of hardware components and software control functions involved in measuring and adjusting a variable that controls an individual process. Closed loop control systems are widely used in industry applications including agriculture, chemical plants, quality control, nuclear power plants, water treatment plants and environmental control. Closed loop control systems enable automation in a number of industrial and environmental settings and regulate processes in industrial control systems (ICS) such as supervisory control and data acquisition (SCADA) and distributed control systems (DCS).

Closed loop control systems are widely used in various industry applications including agriculture, chemical plants, quality control, nuclear power plants, water treatment plants and environmental control.

Unlike open loop control systems or switchable control loops, closed loops don't take input from human operators. This means that other than adjustment by control systems, they operate automatically and independently. In closed loop control, the action is entirely dependent on the process variable. In regards to a heating system, for example, a closed loop might maintain a temperature as a set point, automatically switching on when temperature is below the set point. Open control, in contrast, would enable individuals to set timers and turn instant on heat.

Electric Drives - Motor Controllers and Control Systems

(Description and Applications)

Purpose

For many years the motor controller was a box which provided the motor speed control and enabled the motor to adapt to variations in the load. Designs were often lossy or they provided only crude increments in the parameters controlled.Modern controllers may incorporate both power electronics and microprocessors enabling the control box to take on many more tasks and to carry them out with greater precision. These tasks include:

- Controlling the dynamics of the machine and its response to applied loads.

(speed, torque and efficiency of the machine or the position of its moving elements.) - Providing electronic commutation.

- Enabling self starting of the motor.

- Protecting the motor and the controller itself from damage or abuse.

- Matching the power from an available source to suit the motor requirements (voltage , frequency, number of phases). This is an example of "Power Conditioning" whose purpose is to provide pure DC or sinewave power free from harmonics or interference. Although it could be an integral part of a generator control system, more generally, power conditioning could also be provided by a separate free standing module operating on any power source.

Control System Principles

- Open Loop Systems (Manual Control) In an open loop control system the controlling parameters are fixed or set by an operator and the system finds its own equilibrium state.

- Closed Loop Systems (Automatic Control) Once the initial operating parameters have been set, an open loop system is not responsive to subsequent changes or disturbances in the system operating environment such as temperature and pressure, or to varying demands on the system such as power delivery or load conditions.

- If the loop gain is unity ot greater at the frequency of an input sinusoid where the time delay in the system is equal to half of a cycle period, the sytem will be unstable.

- Three different types of error processing are commonly used in control systems, P, I and D, named after three basic ways of manipulating the error information.

- Proportional - Proportional error correction multiplies the error by a (negative) constant P, and adds it to the controlled quantity.

- Integral - Integral error correction incorporates past experience. It integrates the error over a period of time, and then multiplies it by a (negative) constant I and adds it to the controlled quantity. Equilibrium is based on the average error and avoids oscillation and overshoot providing a more stable system.

- Derivative - Derivative error correction is based on the rate of change of the error and takes into account future expectations. It is used in so called "Predictive Controllers". The first derivative of the error over time is calculated, and multiplied by another (negative) constant D , and also added to the controlled quantity. The derivative term provides a rapid response to a change in the system.

In the case of a motor the desired operating equilibrium may be the motor speed or its angular position. The controlling parameters such as the supply voltage or the load on the motor may or may not be under the control of the operator.

If any of the parameters such as the load or the supply voltage are changed then the motor will find a new equilibrium state, in this case it will settle at a different speed. The actual equilibrium state can be changed by forcing a change in the parameters over which the operator has control.

For continual monitoring and control over the operating state of a system without operator intervention, for more precision or faster response, automatic control systems are needed.

Negative Feedback

To meet these requirements "closed loop" systems are necessary. Also called feedback control systems, or negative feedback systems, they allow the user to set a desired operating state as a target or reference and the control system will automatically move the system to the desired operating point and maintain it at that point thereafter.

Loop Gain The error signal is usually very small so the controlling circuit or mechanism must contain a high gain "error amplifier" to provide the controlling signal with the power to affect the change.

The amplification provided in the loop is called the loop gain.

Loop Delay The response is not always instantaneous as there is usually a delay between sensing the error, or aiming at a new position, and eliminating the error or moving to the new desired position. This delay is called the loop delay.

In mechanical systems the delay may be due to the inertia associated with the lower acceleration possible in getting a large mass to move when a force is applied.

In electrical circuits the delay may be associated with the inductive elements in the circuit which reduce the possible rate of current build up in the circuit when a voltage is applied.

Closed loop control systems must act very quickly to implement the error correction without delay, before the system has time to change to a different state. Otherwise the system will possibly become unstable.

When there is a time lag between sensing of the error and the completion of the corrective action and the loop gain is large enough the system the system may overshoot. If this happens the error will then be in the opposite direction and the control system will also reverse its direction of action in order to correct this new error. The result will be that the actual position will oscillate about the desired position. This instability is called hunting as the system hunts to find its aiming point.

In the worst case, the delayed error correcting response will arrive 180 degrees out of phase with the disturbance it is trying to eleiminate. When this happens the direction of the system response will not act so as to eliminate the error, instead it will reinforce the error. Thus the delay has changed the system response from negative feedback to positive feedback and the system will be critically unstable.

The diagrams below show the response of a control system to a small disturbance.

The Nyquist Stability Criterion is used to predict whether or not a system is unstable from a knowledge of the loop gain and the loop delay as follows

In practical terms, a system with high electrical or mechanical inertia will have a slow response (long delay). With a low magnitude, error correcting action (mechanical force or electrical voltage) the system will be slow in responding (speeding up) but because it is slow, it will also have a low momentum and will tend to settle at the desired operating point when the error correcting force is removed.

The delay in implementing the corrective action however depends on the loop gain.

If, in the same system, the error correcting force is high (amplified / higher loop gain), as in a fast acting system, the system will respond (get moving) more quickly (shorter delay) but it will have correspondingly higher momentum (higher speed of response). When the error correcting force is removed, like any high inertia system, the system's momentum will keep it moving and it will overshoot the target position. Applying the error signal in the opposite direction to bring the system back to its target will cause it to overshoot in the opposite direction.

Nyquist shows how much delay can be tolerated in a system with unity loop gain and defines the point at which the system becomes unstable

History

In the example of a DC electric motor, the desired operating state may be a particular speed. A tachometer is used to measure the actual speed and this is compared to the reference speed. If it is different, an error signal, whose magnitude and polarity correspond to the difference between the reference and the actual speeds, is fed to a voltage controller to change the motor speed so as to reduce the error signal. When the motor is operating at the desired speed the error signal will be zero and the motor will maintain that speed.

PID controllers are also called "3 term controllers".

Motor controllers may be simple open loop systems or they may incorporate several nested closed loop systems operating simultaneously. For example closed loop controls may be used to synchronise the excitation of the stator poles with the angular position of the rotor or simply to control motor speed or the angular position of the rotor.

History

- Four Quadrant Operation When an electrical machine is required to work as both a motor and a generator in both forward and reverse directions this is said to be four quadrant operation. A simple motor which only runs in one direction and is never driven as a generator is an example of a single quadrant application. A motor designed for automotive use which must run in forward and reverse directions and which must provide regenerative braking in both directions needs a four quadrant controller.

Control systems for four quadrant applications will obviously be more complex than single quadrant controls.

Basic Motor Control Functions and Applications

Controllers may have some or all of the following functions many of which have been implemented in integrated circuits.- Speed Control

- DC machines One of the major attractions of brushed DC motors is the simplicity of the controls. The speed is proportional to the voltage and the torque is proportional to the current.

- AC machines The speed of AC motors generally depends on the frequency of the supply voltage and the number of magnetic poles per phase in the stator. Early speed controllers depended on switching in different numbers of poles and control was only available manually and in crude steps. Modern electronic inverters make continuously variable frequency supplies possible permitting closed loop speed control. For speed control in induction motors however the supply voltage must change in unison with the frequency. This requires a special Volts/Hertz controller.

Speed control in brushed DC motors used to be accomplished by varying the supply voltage using lossy rheostats to drop the voltage. The speed of shunt wound DC motors can also be controlled by field weakening. Nowadays electronic voltage control is employed. See below.

Simple open loop voltage control is sufficient when the motor has a fixed load, however open loop voltage control can not respond to changes in the load on the motor. If the load changes, the motor speed will also change. If the load is increased, the motor must deliver more torque to reach an equilibrium position and this needs more current. The motor consequently slows down, reducing the back EMF so that more current flows. To maintain the desired speed, a change in the voltage is needed to provide the necessary current required by the new load conditions. Automatic control of the speed can only be accomplished in a closed loop system. This uses a tachogenerator on the output shaft to feedback a measure of the actual speed. When this is compared with the desired speed, a "speed error" signal is generated which is used to change the input voltage to the motor to drive it towards the desired speed. Note - This is essentially a voltage control system since the tachogenerator usually provides a DC voltage output which is compared with a reference input voltage.

Voltage control alone may be insufficient to cater for wide, fast changing load conditions on the motor since the voltage controller may call for currents in excess of the motor's design limits. A separate current feedback loop may be required to provide automatic current control. The current control loop must be nested within the voltage control loop. This allows the voltage control loop to deliver more current but it can not override the current control which ensures that the current remains within the limits set by the current control loop.

Brushless DC motors are powered by a pulsed DC supply to create a rotating field and the speed is synchronous with the frequency of the rotating field. Speed is controlled by varying the supply frequency. See also Inverters below.

- Torque Control If the application requires direct control over the motor torque rather than the speed, in simple machines this can be accomplished by controlling the current, which is proportional to the torque, and omitting the speed control loop. For more precise control, vector controllers are used.

- Voltage Control It is no longer necessary to use energy wasting rheostats to provide a variable voltage.

- Voltage Choppers Modern controllers use switching regulators or chopper circuits to provide a variable DC voltage from a fixed DC supply. The DC supply is switched on and off at high frequency (typically 10 kHz or more) using electronic switching devices such as MOSFETs, IGBTs or GTOs to provide a pulsed DC wave form. The average level of the output voltage can be controlled by varying the duty cycle of the chopper.

- Pulse Width Modulation (PWM) AC voltages can be similarly controlled using bi-directional pulses to represent the sinusoidal wave.

- Linear Voltage Regulators For low power applications a series or linear regulator is often used. It is less efficient than a switching regulator since the variations in voltage must be taken up, and the associated power dissipated, by the volt dropping series transistor but it provides a pure DC. Series regulators are not suitable for high power applications such as electric traction where efficiency is paramount.

- Thyristor Voltage Control With AC supplies, Thyristors (SCR)s can be used in series with the load to create a variable voltage by blocking the passage of current to the load for the initial part of the cycle and turning the current on by applying a signal to the gate of the SCR. A single SCR only affects one polarity of the waveform. To switch both the positive and negative going current requires two SCRs connected in parallel and in opposite polarity or a triac (bidirectional SCR). By varying the delay (the phase angle) before the current is turned on, the average current, and thus the average voltage seen by the load, can be varied as shown below.

- Current Control

In many motor applications the motor

current may lag the supply voltage due to the inductance in the circuit

and it is often desirable to control the current directly, rather than

the voltage, to obtain more precise or faster control of the current and

hence the torque. In this case a shunt resistor or a current

transformer is used to monitor the current. The difference between the

actual and reference currents is used in a high gain feedback loop to

provide the necessary current regulation.

- Current control is particularly important for induction

motors to protect the motor from excessive start up currents. A current

feedback signal is used to change the firing angle of thyristors in the

rectifier or inverter circuits to limit the current within its reference

value.

- Converters This a generic term for circuits which may provide AC or DC outputs from either AC (mains frequency) or DC (battery) supply lines. They include power bridges for rectifying the AC supply and inverters for generating an AC waveform from a battery supply.

- Buck and Boost Converters Buck and boost converters are DC-DC converters, the DC equivalent of AC transformers.

- Buck Converter The buck converter is used to reduce the DC voltage. The chopper above is an example of a step down DC converter.

- Boost Converter The boost converter is used to step up the DC voltage.

- Inverters Inverters provide a controlled alternating current (AC) supply from a DC or AC source. There are two main classes of applications:

- Providing a fixed output from a variable source Inverters designed to deliver regulated AC mains power from sources which may have a variable input voltage (either AC or DC) or in the case of AC input power, a variable frequency input. Such applications may include emergency generating sets, uninterruptible power supplies (UPS) or distributed power generation from wind and other intermittent resources. All must deliver a fixed output voltage and frequency to the load since the applications expect it and may depend on it.

- Providing a variable output from a fixed source On the other hand, many applications require inverters to accept a fixed AC voltage and frequency from the mains and to provide a different or variable voltage and frequency for applications such as motor speed control. .

- Volts/Hertz Control Volts/Hertz control is needed for speed control of induction motors. In an open loop system the control system converts the desired speed to a frequency reference input to a variable frequency, variable voltage inverter. At the same time it multiplies the frequency reference by the Volts/Hertz characteristic ratio of the motor to provide the corresponding voltage reference to the inverter. Changing the speed reference will then cause the voltage and frequency outputs from the inverter to change in unison.

- Cycloconverter The cycloconverter converts AC supply frequency directly to a variable frequency AC without the intermediate DC link stage.

- Vector Control - Flux or Field Oriented Control (FOC) All motors need a magnetising current and a torque producing current. In a brushed DC motor, these two currents are fed to two different windings. The magnetising current is fed to the stator or field winding and the torque producing current is fed to the rotor winding. This allows independent control of both the stator and the rotor fields. However in brushless motors such as permanent magnet motors or induction motors it is not possible to control the rotor field directly since there are no connections to it. Because the parameters to be controlled can not be measured, their values must be derived from parameters which can be measured and controlled. The only input over which control is possible is the input current supplied to the stator.

- Vector Control Summary

- Objectives Maximum current-to-torque power conversion, fast transient response, precise control of torque, speed and position.

- Requires Rotating flux to be maintained at 90 degrees to the rotor flux.

- Inputs Available information (status of stator voltages and currents and rotor position and/or speed).

- Uses Two independent control loops to provide control of the magnetising and torque producing current vectors.

- Calculates Error Mathematical transforms to analyse input signals from the stator and calculate any deviation from the desired conditions of the rotor.

- Calculates Correction Mathematical inverse transforms to convert the rotor error signal back into control signals to be applied to the stator to counteract the error.

- Activates A pulse width modulated (PWM) inverter providing power to the motor.

- Produces Stator input voltage waveforms of the correct amplitude, frequency and phase to effect the change.

- Method 1 Direct Control Uses position sensors and complex mathematical transforms

- Method 2 Indirect Control "Sensorless" Uses even more complex mathematical transforms

(Both of the above methods use current sensors for current control of the stator windings) - Repeats Samples status and provides control signals at 20 kHz to provide continuous control.

- Additional Benefits Low speed control, efficiency improvement, smaller motors.

- Transient Response Despite its many advantages, the venerable induction motor is relatively slow to respond to changes in load conditions or user commands for changes in speed. This is mainly because the rotor current can not instantaneously follow the applied voltage due to the delay caused by the inductance of the motor's windings.

- Efficiency The inductive phase lag noted above also causes an instantaneous loss of torque and reduced efficiency because the torque producing flux from the stator is not acting at 90 electrical degrees to the rotor field.

- Implementation The two control methods outlined below each describe the processing of one sample of the motor status and how error correction occurs. They both involve considerable mathematical processing power. The motor however needs continuous real time control to regulate the speed and torque and this needs sampling rates of 20 kHz or more increasing the signal processing load dramatically. This task is well within the scope of Digital Signal Processors (DSPs), special purpose integrated circuits designed for computationally intensive applications.

- Direct control This method uses a position sensor to determine the angular position of the rotating shaft. The angle between the rotor flux and the rotating flux wave is the sum of the angular position of the shaft and the slip angle which can be derived from the rotor current. The position error (deviation from 90 degrees) is a measure of the required torque producing component of the stator current. This signal can then be used as the basis for a conventional current control loop.

- Indirect - Sensorless Control Sensorless control only refers to the elimination of the position sensor used in the scheme above. The control system may have several other sensors. The position information provided by the position sensor can also be derived from mathematical transforms on the stator currents and voltages just as the flux is in the direct system. Since the sensor adds physical complexity and cost to the machine, and since the cost of computing power is constantly reducing, replacement of the sensor by mathematical techniques is now economically justified.

- Servo Systems Many of the techniques involved in vector control are applicable to servo systems and consequently vector controlled system are replacing some of the traditional servo systems.

- Ward Leonard Controller The Ward Leonard speed controller provides a variable speed drive from the fixed voltage and frequency AC mains electric supply. It uses three machines, an AC induction motor driven at a fixed speed from the mains supply, driving a DC generator which in turn powers a shunt wound DC motor, usually of similar construction to the generator. The DC output from the generator is directly connected to the armature of the DC motor. The motor speed is adjusted by using a rheostat to adjust the excitation current in the field winding of the generator to vary the generator output voltage. Ward Leonard controllers can still be seen in passenger lifts (elevators) throughout the world as well as on electric cranes, winding gear in coal mines and industrial process machinery though they have now largely been superceded by thyristor speed controllers.

- Position Control Stepping motors are usually employed when accurate position control is required. Accurate positioning is possible with an open loop system by counting pulses applied to the motor. Potentiometers can be used to provide position feedback in closed loop systems but shaft encoders provide more precise travel feedback by counting pulses.

- Electronic Commutation The function of the commutator is to change the direction of the motor energising current as alternate rotor poles pass the stator poles. In brushless DC motors, the mechanical commutator is eliminated and the energising current is provided by the stator coils. Commutation is carried out by electronic switches which reverse the stator current as alternate rotor poles pass by the stator poles. This requires a position sensor to feedback the angular position of the rotor shaft to the motor controller to enable it to switch the direction of the current when the rotor poles are in the correct position with respect to the stator poles.

- Starting Some motor designs are not self starting when the power is applied. Such problems are usually addressed by the machine designer using auxiliary windings or other methods and are usually not apparent to the user.

- Regenerative Braking The battery can only capture the maximum regenerative braking energy if the regen volts are greater than the battery volts. With a DC motor this needs a variable DC - DC converter whose output is based on motor speed to convert high current low voltage pulses from low speed braking to high voltage low current pulses. The control system must also step down any regen voltage which exceeds the battery's upper charging voltage limit to avoid damaging the battery and it must dump any excess energy into a resistive load when the battery reaches its full state of charge (SOC) of 100% or the current reaches the battery's recommended charging current limit. This is particularly important for Lithium batteries.

- Power Factor Correction To avoid unnecessary losses, or to meet the acceptable load requirements of the energy supply utility, power factor correction is often required with induction motors, particularly for large machines or in installations running many machines.

- Protection The control systems outlined above are also designed to ensure that the electrical machine does not exceed its design voltage and current limits. In addition the machine may incorporate several simple protection devices.

- Sensors Some examples of the many types of sensors used in motor control systems are given below.

- Current -

- Current shunt - Inexpensive, lossy.

- Current transformer - Efficient, AC only - can not measure DC.

- Hall effect sensor.

- Voltage - A to D converters.

- Frequency - Pulse counting.

- Phase - Derived from time differences between measured and reference sources.

- Temperature - Thermistors, thermocouples.

- Light - Photoelectric and fibre optics.

- Magnetic flux - Hall effect sensor.

- Position - Linear and angular.

- Optical encoders (based on a light source, a code wheel and an optical detector).

- Pulse counters - Linear and angular displacements. Pulses may be magnetic or optical.

- Potentiometers - Limited range, low accuracy.

- Speed - Tachogenerators based on various principles.

- Rotary DC generator - Provides a voltage output.

- Pulse counters - Pulses may be magnetic or optical.

- Centrifugal switch (Limit switch).

- Torque - Usually derived from motor current.

- Time - Microprocessor clock.

Variable voltages can also be generated by using fixed pulse widths but by varying instead the pulse amplitude (Pulse Amplitude Modulation - PAM) or the pulse repetition frequency (Pulse Frequency Modulation - PFM).

A voltage controller may be activated manually in

an open loop system but for continuous voltage control, an inverter

must be incorporated into a feedback loop in a closed loop system. The

control system monitors the actual output voltage and provides a control

signal, which may be an analogue or digital representation of the error

signal, to the pulse width modulator to correct any deviations. When

voltage control is used for speed control the error signal may be

derived from a tachogenerator on the motor output shaft.

Electronic voltage control is also an essential part of many generator applications. In automotive systems the generator or alternator is driven at a variable speed which depends directly on the engine speed. It must give its full voltage output at the lowest speed but the voltage must be maintained as the engine speed rises. Alternators used in 12 Volt systems usually have built in voltage regulation. In HEV applications a chopper regulator is used at the output of the generator to maintain the voltage at the DC link within strict limits to avoid damaging the battery. When the battery is fully charged, the battery's own management system disconnects it from the supply to prevent overcharging.

This is the same principle as used in light dimmer switches.

Gate turn off thyristors (GTOs) can be used to switch off the current as well as switching it on allowing more control over the duration of the current through the device.

The circuit below shows the principle of such an inverter designed for three phase applications.

Three phase variable frequency inverter

The three phase sinusoidal input is fed to a simple diode full wave bridge rectifier block delivering a fixed voltage to the inverter. The connection between the rectifier and the inverter is known as the DC Link. The inverter transistors are switched on in the sequence of their numbers as shown in the diagram with a time difference if T/6 and each transistor is kept on for a duration of T/4 where T is the time period for each complete cycle. The example above provides six possible current configurations and is known as a six step inverter.

The diodes connected across the switching transistors are known as "freewheel or flywheel diodes". Their purpose is to provide a current bypass path around the transistor to protect it from the dissipation of the stored energy in the inductive load (the motor) when the transistor is switched off. The current through the diode "freewheels" until all the energy in the inductive load is dissipated.

The output line voltage wave form for each phase is shown below.

The amplitude of the output wave is determined by the level of the DC supply voltage to the inverter block but it can be varied by thyristor (SCR) control of the rectifier circuit to provide a variable voltage at the DC link.

Instead of transistor switches, the inverter may use MOSFETs, IGBTs or SCRs.

Free-wheeling diodes connected across the transistors protect them from reverse bias inductive surges due to motor field decay which results when the transistors turn off by providing free wheeling paths for the stored energy.

The waveforms for traction applications are often stepped waves rather than pure sinusoids since they are easier to generate and the motor itself smoothes out the wave.

Variable frequency inverters are used when variable speed control is required. The frequency of the wave is controlled by a variable frequency clock which initiates the pulses.

For speed control in AC machines the voltage and frequency must vary in unison. See AC motor speed control. In open loop systems the operating point is set by a speed reference and the equilibrium speed is determined by the load torque. A closed loop system allows a fixed speed to be set. This requires a tachogenerator to provide a feedback of the actual speed for comparison with the desired speed. If there is a difference, an error signal is generated to bring the actual speed into line with the reference speed by adjusting both the voltage and the frequency so as to eliminate the speed difference.

In a closed loop system a speed feedback signal provided from a tachogenerator on the motor output shaft is used in the control loop to derive a speed error signal to drive a Volts/Hertz control function similar to the one outlined above.

As with large DC motors, speed control is normally accompanied by current control.

The system is complex and works by sampling the voltage of each phase of the AC supply and synthesising the desired output waveform by switching on to the load for the duration of the sampling period, the phase whose voltage is closest to the desired voltage at the instant of sampling. The output waveform is severely distorted and the capability of induction motors to cope with the very high harmonic content limits the maximum frequency for which the system can be used.

Cycloconverters are only suitable for very low frequencies, up to 30% of the input frequency. They are used for low speed high power drives to eliminate the need for a gearbox in heavy rolling and crushing mills and in traction applications for trains and ships.

The actual stator current is the vector sum of two current vectors, the inductive (phase delayed) magnetising current vector producing the flux in the air gap and the in phase, torque producing, current. To change the torque we need to change the in phase, torque producing, current but because we want the air gap flux to remain constant at its optimum level, the magnetising current should also remain unchanged when the torque changes.

Vector Control or Field Oriented Control is a method of independently varying the magnitude and phase of the stator current vectors to adapt to the instantaneous speed and torque demands on the motor.

It enables parameters over which no direct control is possible to be changed by changing instead, parameters which can be measured and controlled.

For many applications vector control is not necessary, but for precision control, optimum efficiency and fast response, control over the rotor field is needed and alternative methods of indirect control have been developed. Because of the low cost of computing power, vector control is being used in more and more brushless motor applications.

During the transition period the flux amplitude and its angle with respect to the rotor must be maintained so that the desired torque can be developed.

Torque also depends on the magnitude of the flux but this depends on the inductive component of the current and can not be changed instantaneously. In any case the flux density is set to its optimum point before saturation occurs.

Vector control is a way of changing the in phase current vector without changing the inductive magnetising current vector so that the machine response time is not subject to inductive delay.

The torque on the rotor of any motor is at its maximum when the magnetic field due to the rotor is at right angles to the field due to the stator.

The vector control system provides instantaneous adjustments to the stator currents to control the position of the rotor with respect to the moving flux wave thus avoiding losses due to phase lag.

Once the motor has a computer on board other functions such as communications and the controller area network (CAN Bus) can be integrated with the motor controls.

The vector control system is essentially an indirect system using information about the system gained from a knowledge of the stator voltages and currents and its position. Both the "direct" and "indirect" control methods referred to below indicate how the information about the rotor position is obtained.

To obtain the necessary information about the stator currents in a three phase system it is only necessary to measure two of the three phase currents supplying the motor since the algebraic sum of the currents flowing in two windings must equal the current flowing out of the third winding.

The flux component of the stator current must be calculated from a mathematical model of the motor. A mathematical transform (Clarke-Park transformation) is carried out on the actual stator currents to derive a measure of the actual flux and a representation of the deviation from the desired value. The inverse transform is used to derive the corresponding error correcting signals to be applied to the input of a variable frequency inverter to generate the appropriate stator currents (amplitude, frequency and phase) to correct the error.

The mathematical transforms require accurate inputs on the mechanical and electrical characteristics of the machine which are often difficult to measure or estimate. Self learning adaptive control systems have come to the rescue to generate the necessary reference data from measurements of the actual performance.

The control algorithms must also take into account environmental conditions. For instance the motor winding resistance (and hence the L/R time constant of the motor) depends on the temperature and the affect of temperature changes needs to be incorporated into the model.

The sensorless control method can be used to control motor speed almost down to zero.

History

When long distances to the target or many motor revolutions are involved, it may be desirable to speed up the motor during the travel. In this case speed control may be provided by a feedback loop.

One problem faced by the user however is that starting in many machines is accompanied by a very high inrush current which is potentially damaging to the motor or its power supply. Current control systems outlined above are used to overcome this problem.

To capture regenerative braking energy from induction motors requires the synchronous speed to be reduced below the motor speed by reducing the supply frequency. See Generator Action.

The most common power factor correction is by means of added capacitors however, under certain circumstances the motor controller can also be used for this purpose

Under light load conditions the magnetising current in an induction motor is relatively high with respect to the load current causing a low power factor. (See Induction Motors). As the load is increased, the in phase load current increases with respect to the magnetising current thus improving (increasing) the power factor.

The motor controller can be used to address the problem of low power factor in lightly loaded machines. If the supply voltage is reduced at light load levels, the air gap flux will be reduced accordingly and the current (and slip) will have to increase to produce the same torque. The effect is to increase the load current with respect to the magnetising current, reducing the current lag and increasing the power factor. Simple thyristor control of the supply voltage will be sufficient to provide the necessary voltage control to implement this scheme.

This method of power factor control is only practical for lightly loaded machines. With heavily loaded machines the power factor is normally reasonably high and the effect of voltage control is not significant.

If it overheats, a temperature sensor or thermistor will cause the power to be switched off or cooling systems to be switched on. If it exceeds a safe speed limit, a centrifugal switch will interrupt the current.

Practical Controllers

- Simple low cost, low power machines usually have simple open loop control systems. The common DC brushed motor for instance needs only a simple voltage controller for speed control and low cost, integrated circuit controllers are available for this purpose.

- Higher power machines however tend to use more complex closed loop controllers which are usually custom designed for each particular machine and often built into the machine itself.

- The electronic circuits in the motor controller must be able to handle the full motor power and this may be a limiting factor in the design of a drive train. The main influencing variable is the maximum peak output current, because this defines the cost of the power electronics for a given maximum voltage. It is often necessary to use liquid cooling to accommodate the high power levels demanded by the motor.

- Polyphase machines need one set of power and control circuits per phase. The cost of the controller often limits the number of practical motor phases to typically 3 or 4.

- Safety features also play a more important role in larger machines since in case of machine failure the potential for damage is greater.

- Inverters, converters and commutator circuits used in motor controllers all switch very high currents are thus likely to be a source of Radio Frequency Interference (RFI). The system designer should also be aware of the consequences that high frequency, high current pulsed loads of the inverters and choppers may have on battery lifetime in DC traction systems such as hybrid electric vehicles. Similarly the voltage regulation of the on board generator and the regenerative braking charge pulses can also affect the battery adversely if not properly controlled.

Electronic spreader control system

Modern manufacturing and process industries are often largely run by distributed control systems (DCSs), with minimal input from operating personnel. This has largely been made possible by the evolution of computer and controller hardware and software.

The basic building block of a process control systems is the process control loop. Process control loops utilize sensors, transmitters, calculations or algorithms, processing systems, and actuators or outputs. Their ultimate goal is to help a process run in a stable, predictable, consistent manner.

A large industrial processing facility, like an oil refinery or paper mill, utilizes thousands of process control loops. This type of facility also typically utilizes a data historian to store data related to their control system or systems, plus other significant data. This data contains a wealth of information that can be used as a powerful troubleshooting or optimization tool.

What is a process control loop?

A simple single-input-single-output (SISO) feedback control loop consists of following:

Process Input

An outside variable that affects a process. In a control loop, you must be able to control and manipulate this variable. For example, the steam flow into a tank could be the process input in a control loop controlling the fluid temperature out of a tank. (Note that the process input is sometimes referred to as the “input variable.”)

Process Output

A characteristic of the process that affects the outside world. In a process control loop, this must be measurable and vary in a consistent wa y with the process input. In the tank temperature control example, the temperature of the fluid exiting the tank would be the process output. (The process output is sometimes referred to as the “output variable.”)

Set point

The desired value for the process output. In the tank example, this is the desired temperature of the fluid.

Controller

The hardware and software which compare the measured process output to the setpoint, and calculates if the process input needs to change and by how much. The controller then sends a signal to an actuator to make an adjustment to the process input, if necessary. In the tank example, this could be an actuator on a control valve on the steam line to the tank.

What type of data do historians store?

PV or MV

The process variable or measured variable. This is the measured value of the process output – in this case, the temperature of the fluid exiting the tank. This value is transmitted from the sensor to the controller.

SP

The setpoint value, which is the desired value for the process variable (PV). The desired setpoint value can be entered by an operator, or it can be calculated or based on a signal from an outside source.

OP

The output from the controller. The output signal is transmitted from the controller to an actuator to make an adjustment, if necessary, or it can be sent to another controller (this is described in greater detail in the next bullet).

Mode

This determines when and how a controller works. The three most common controller modes are Automatic, Manual, and Cascade.

In Automatic mode, the controller receives the setpoint value (SP) and the measured value of the process variable (PV), and calculates and sends an output signal (OP) to the actuator.

In Manual mode, the controller is overridden, allowing operating personnel to send the output signal (OP) directly to the actuator.

Cascade mode is similar to Automatic mode, except the controller receives its setpoint (SP) from an outside source, usually another controller. To help illustrate this concept, imagine in our tank example if the temperature controller sent an output (OP) signal to a steam flow controller instead of a valve actuator. The steam flow controller would receive a setpoint (SP) from the temperature controller, plus a PV signal from a flow meter on the steam flow into the tank, and calculate and send an output signal (OP) to the actuator. This “Cascade” control strategy would improve the temperature control response because it would largely remove outside influences, such as variations in the steam supply or any control valve non-linearity. (Note that this is no longer a simple single-input-single-output control loop.)

Time trends of the other process control values can also be helpful:

- Setpoint (SP) trends reveal the changes that have occurred to operator-entered setpoint values and calculated setpoint values. This is valuable because unauthorized or unwarranted setpoint changes can lead to process instabilities and upsets.

- Mode trends show when controllers have been put into Automatic, Manual and Cascade modes. Like setpoint changes, mode changes can lead to process instabilities and upsets.

- Controller output (OP) trends can reveal problems with equipment or the process. For example, if a previously functioning control loop has moved to an output of 0% or 100%, and is failing to meet the setpoint, that is a good indication of an equipment malfunction or a change in the process.

_________________________________________________________________________________

Tidak ada komentar:

Posting Komentar