Advantages and Disadvantages of Electronic Communication

Technology in Modern Communication

Communication is needed for decision-making, coordination, control, and planning. Communication is required for processing information in the accounting department, finance department, personnel department, establishment, of public relations, sales department, market research, production department, purchase department etc. Communication with the government, shareholders, and prospective investors, customers etc. is also required for the day to day functioning of the business concern. The conventional process of communication is not sufficient to meet the multidimensional needs of the firm enterprises. So, the need for modern communication technology emerges to meet the desired need of modern business operations. Worldwide communication has been facilitated by the electronic transmission of data which connects individuals, regardless of geographic location, almost instantly.

Definition of Electronic Communication

Communication using electronic media known as electronic communication. Such communication allows transmission of message or information using computer systems, fax machine, e-mail, title or video conferencing and satellite network. People can easily share conversation, picture, image, sound, graphics, maps, interactive software and thousands of things for the development of electronic communication. Due to electronic technology, jobs, working locations and cultures are changing, and therefore people can easily access to worldwide communication without any physical movement.

L.C. Bovee and Others said, “Electronic communication is the transmission of information using advanced techniques such as computer moderns, facsimile machines, voice mail, electronic mail, teleconferencing, video cassettes, and private television networks.”

Advantages of Electronic Communication

The following points highlight on the advantages of electronic communication:

1. Speedy transmission: It requires only a few seconds to communicate through electronic media because it supports quick transmission.

2. Wide coverage: World has become a global village and communication around the globe requires a second only.

3. Low cost: Electronic communication saves time and money. For example, Text SMS is cheaper than the traditional letter.

4. Exchange of feedback: Electronic communication allows the instant exchange of feedback. So communication becomes perfect using electronic media.

5. Managing global operation: Due to the advancement of electronic media, business managers can easily control operation across the globe. Video or teleconferencing e-mail and mobile communication are helping managers in this regard.

Disadvantages of Electronic Communication

Electronic communication is not free from the below limitations:

1. The volume of data: The volume of telecommunication information is increasing at such a fast rate that business people are unable to absorb it within the relevant time limit.

2. The cost of development: Electronic communication requires huge investment for infrastructural development. Frequent change in technology also demands further investment.

3. Legal status: Data or information, if faxed, may be distorted and will cause zero value in the eye of law.

4. Undelivered data: Data may not be retrieved due to system error or fault with the technology. Hence required service will be delayed

5. Dependency: Technology is changing every day, and therefore developing countries face the problem as they cannot afford the new or advanced technology. Therefore developing countries need to be dependent towards developed countries for sharing global network.

XXX . V0 Modern Finance Theory

This timely text examines the role that financial markets and institutions play in modern macroeconomics. Over the last couple of decades there has been a fair amount of research on microeconomic models of market failure and the impact of such failures on business cycles and other macroeconomic phenomena. the importance of having efficient financial markets in achieving economic growth, and the constraints on growth in the absence of a working financial system.

Outcomes are easy to measure in financial markets: you either beat the index or you don’t. And the results could not be clearer about how few people possess any real skill.

Experts, not traders, would set the prices of the securities in the marketplace. “The time seems to be ripe for the publication of elaborate monographs on the investment value of all the well-known stocks and bonds listed on the exchanges,” he wrote. “The last word on the true worth of any security will never be said by anyone, but men who have devoted their whole lives to a particular industry should be able to make a better appraisal of its securities than the outsider can.”

Williams’s new science of investing featured the now-familiar dividend discount model. In short, this model quantifies the idea that the investment value of a security is equal to “the present worth of the expected future dividends.”7 Williams laid this out in simple formula form:

Armed with this formula and a desired rate of interest, investors needed only a way to forecast future dividends. Williams believed he had a straightforward solution. The investor should “make a budget showing the company’s growth in assets, debt, earnings, and dividends during the years to come.”8 Rather than using an accountant’s ledger book, however, Williams proposed that investors use algebraic formulas instead. Williams believed that growth could be modeled using a logarithmic curve:

With this logarithmic model for growth (the familiar “S-curve” that Bain & Company consultants so dearly love) and a few additional formulas to provide the “terminal value” once competitive forces had stalled growth, Williams believed the true value of a company could be determined.

Combining a company’s budget with these new algebraic formulas offered an approach that Williams believed was “altogether new to the accountant’s art.” Williams grew almost giddy with excitement contemplating the beauty of his new technique. “By the manipulation of algebraic symbols, the warp of development is traced through the woof of time with an ease unknown to ordinary accounting.”9 One can only imagine what literary metaphors might decorate Williams’s prose had he lived to see the modern Excel model!

Yet as he waxed philosophical about the new art of algebraic accounting, Williams acknowledged that some might be skeptical of the supposed ease of his method. “It may be objected that no one can possibly look with certainty so far into the future as the new methods require and that the new methods of appraisal must therefore be inferior to the old,” he wrote. “But is good forecasting, after all, so completely impossible? Does not experience show that careful forecasting—or foresight as it is called when it turns out to be correct—is very often so nearly right as to be extremely helpful to the investor?”10

Williams acknowledged this key limitation of his model—uncertainty about the future. But this, he argued, was a problem for others, not the fault of his beautiful mathematical models. “If the practical man, whether investment analyst or engineer, fails to use the right data in his formulas, it is no one’s fault but his own,” he wrote.11

Williams’s theories had grown out of the chaos of the Crash of 1929, and he retained a pessimism about the “practical men” that were his contemporaries. “Since market price depends on popular opinion, and since the public is more emotional than logical, it is foolish to expect a relentless convergence of market price towards investment value,” he wrote.12

But the generation of finance researchers emerging after World War II was more optimistic. The success of American industry—and American science—in defeating the Nazis inspired confidence in a new generation of researchers who believed that better math and planning could change the course of human affairs.

Markowitz, Sharpe, and the Capital Asset Pricing Model

Harry Markowitz was one of these men. Born in 1927, a teenager during the war, he studied economics at the University of Chicago in the late 1940s. After Chicago, Markowitz researched the application of statistics and mathematics to economics and business first at the Cowles Commission and then at the RAND Corporation. He was at the epicenter of the new wave of technocratic, military-scientific planning institutes.Markowitz understood the key problem with Williams’s ideas. “The hypothesis (or maxim) that the investor does (or should) maximize discounted return must be rejected,” he wrote in his 1952 paper.13 “Since the future is not known with certainty, it must be ‘expected’ or ‘anticipated’ returns which we discount.”

Without accounting for risk and uncertainty, Markowitz observed, Williams’s theory “implies that the investor places all his funds in the security with the greatest discounted value.”14 This defied common sense, however, and so Markowitz set out to update Williams’s theory. “Diversification is both observed and sensible; a rule of behavior which does not imply the superiority of diversification must be rejected both as a hypothesis and as a maxim,” he argued.15

Markowitz’s explanation for why diversification was both observed and sensible was that investors care about both returns and about “variance.” By mixing together different securities with similar expected returns, investors could reduce variance while still achieving the desired return. Investors, he believed, were constantly balancing expected returns with expected variance in building their portfolios.

The logical next step in this argument was that the prices of different assets should have a linear relationship to their expected variance to maintain a market equilibrium where one could only obtain a higher return by taking on a higher amount of variance. This was the logic of the Capital Asset Pricing Model developed by Markowitz’s student William Sharpe.

Sharpe’s Capital Asset Pricing Model was meant as “a market equilibrium theory of asset prices under conditions of risk.”16 He believed that “only the responsiveness of an asset’s rate of return to the level of economic activity is relevant in assessing its risk. Prices will adjust until there is a linear relationship between the magnitude of such responsiveness and expected returns.”17 Sharpe measured responsiveness by looking at each security’s historical variance relative to the market, which he labeled its beta.

To be sure, not everyone from Williams’s era was so enthusiastically enamored with the prospect of experts planning the appropriate pricing of investments. At the same time as Williams was completing his 1937 dissertation, Friedrich Hayek was attacking this type of planning mindset. If society were turned over to experts and planners, he wrote:

change will be quite as frequent as under capitalism. It will also be quite as unpredictable. All action will have to be based on anticipation of future events and the expectations on the part of different entrepreneurs will naturally differ. The decision to whom to entrust a given amount of resources will have to be made on the basis of individual promises of future return. Or, rather, it will have to be made on the statement that a certain return is to be expected with a certain degree of probability. There will, of course, be no objective test of the magnitude of the risk. But who is then to decide whether the risk is worth taking?18Alas, it would be another forty years before the notion of state planning by experts generally fell out of fashion and Hayek was given the Nobel Prize for his 1940s era work on price discovery in the broader field of economics. It is enough to note for our purposes that in financial economics many of the hangovers of the Williams/Markowitz/Sharpe era, and its religious faith in algebraic calculations and experts’ forecasting power, lasted well beyond the nightmare of the 1970s.

The Empirical Invalidation of Modern Finance Theory

The intellectual history of modern finance theory thus followed a simple logical flow. A stock is worth the net present value of future dividends. But investors must not only care about expected return—otherwise they would put all their money in one stock—they must also care about the variance of their investment portfolios. If investors want to maximize expected return and minimize expected variance, then expected variance should have a linear relationship with expected return.This is the core idea: combining a forecast of future cash flows with an assessment of future variance based on the historical standard deviation of a security’s price relative to the market should produce an “equilibrium” asset price.

Williams, Markowitz, and Sharpe were all brilliant men, and their models have a certain mathematical elegance. But there is one big problem with their theoretical work: their models don’t work. The accumulated empirical evidence has invalidated nearly every conclusion they present.

Robert Shiller won the Nobel Prize for conclusively proving that the dividend discount model was a failure. In a paper for the Cowles Commission thirty years after Markowitz’s work was published, Shiller took historical earnings, interest rates, and stock prices, and calculated the true price at every moment of every stock in the market with the benefit of perfect hindsight. He found that doing this could explain less than 20 percent of the variance in stock prices. He concluded that changes in dividends and discount rates could “not remotely justify stock price movements.”

Below is a graph showing the actual future value of earnings discounted back at the actual interest rates relative to the actual stock market index over time. As you can see, the stock market index is far more volatile than could possibly be explained through the dividend discount model.

Future earnings and interest rates do not explain stock price movements as Williams thought they would. Variance also fails to explain stock prices, as Markowitz and Sharpe thought they would.

In a review of forty years of evidence, Nobel Prize winner Eugene Fama and his research partner Ken French declared in 2004 that the Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM) was bunk: “despite its seductive simplicity, the CAPM’s empirical problems probably invalidate its use in applications.”19 These models fail because they assume predictability: they assume that it is possible to forecast future dividends and future variance by using past data.

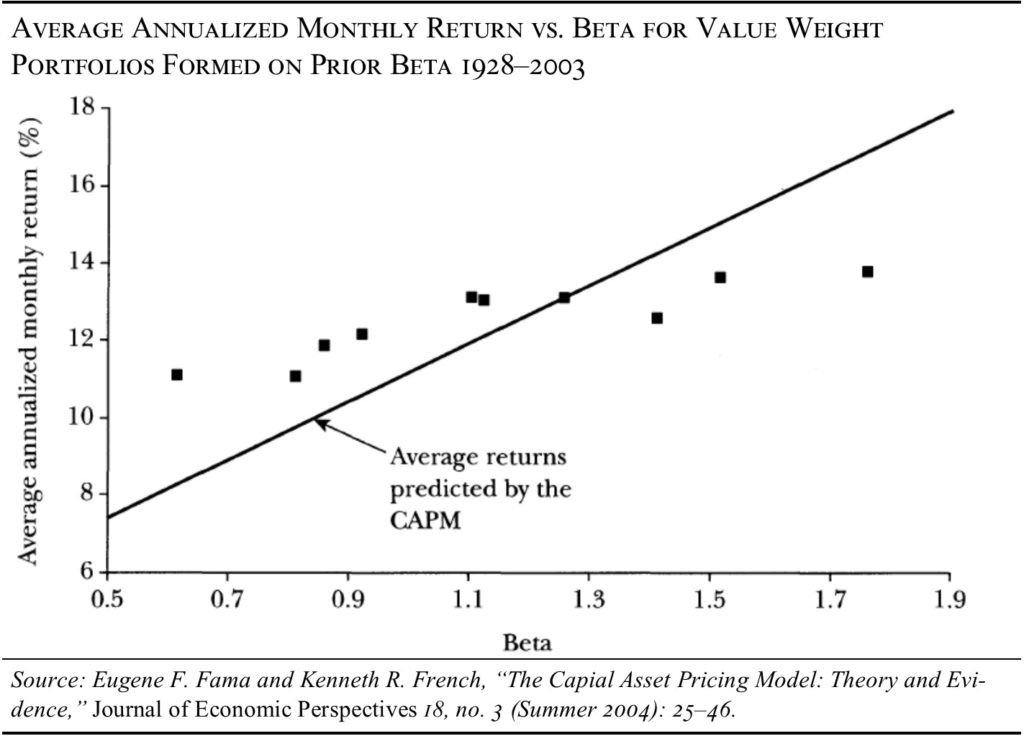

The core prediction of the model—that stocks with higher price volatility should produce higher returns—has failed every empirical test since 1972. Below is a graph from Fama and French showing CAPM’s predictions relative to reality.

A New Philosophy of Unpredictability

So what is the alternative? A philosophy based on unpredictability. As we have seen time and time again, experts cannot predict the future. The psychologist Philip Tetlock ran a twenty-year-long study in which he picked 284 experts on politics and economics and asked them to assess the probability that various things would or would not come to pass.20 By the end of the study, in 2003, the experts had made 82,361 forecasts. They gave their forecasts in the form of three possible futures and were asked to rate the probability of each of the three. Tetlock found that assigning a 33 percent probability to each possible alternative future would have been more accurate than relying on the experts.Think back to 2016: The experts told us that Brexit would never happen. They told us that Trump would never win the Republican primary, much less the general election. In both cases, prominent academics and businessmen warned of terrible consequences for financial markets (consequences that, of course, never came to pass). These are only two glaring examples of the larger truth Tetlock has identified: experts are absolutely terrible when it comes to predicting the future.

Stanford economist Mordecai Kurz argues that there are a variety of rational interpretations of historical data that lead to different logical predictions about the future (just think of all the different analysts and researchers currently putting out very well-researched and very well-informed predictions for the price of oil one year from now). But only one of those outcomes will come true, and when the probability of that one outcome goes from less than 100 percent to 100 percent, every other alternative history is foreclosed.21 Kurz has developed a model that explains 95 percent of market volatility by assuming that investors make rational forecasts that future events nevertheless prove incorrect.

The forecast error arises from investors’ inability to accurately predict the future. What looks inevitable in retrospect looks contingent in the moment, the product of what Thomas Wolfe called “that dark miracle of chance that makes new magic in a dusty world.”

In his 1962 classic The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, historian of science Thomas Kuhn posited that scientists rely on simplified models, or paradigms, to understand the observed facts. These paradigms are used to guide scientific enquiry until such enquiry turns up facts that cast these paradigms into doubt. Scientific revolutions are then required to develop new paradigms to replace the old, disproven ones.

The economists Harrison Hong, Jeremy Stein, and Jialin Yu have posited that markets function in a similar way.22 Investors come up with simplified models to understand individual securities. When events unfold that suggest that these simple models are incorrect, investors are forced to revise their interpretation of historical data and develop new paradigms. Stock prices move dramatically to adjust to the new paradigm.

Ever-changing paradigms are necessary because the world is infinitely complex, and forecasting would be impossible without simplification. Think of all of the many things that affect a stock’s price: central bank policy, fund flows, credit conditions, geopolitical events, oil prices, the cross-holdings of the stocks’ owners, future earnings, executive misbehavior, fraud, litigation, shifting consumer preferences, etc. No model of a stock’s price could ever capture these dynamics, and so most investors rely instead on dividend discount models married to investment paradigms (e.g., a growth investor who looks for companies whose growth is underpriced relative to the market combines a paradigm about predicting growth with a dividend discount model that compares the rate of that growth to what is priced into the stock). But both these dividend discount models and these investment paradigms are too simple and are thus frequently proven wrong.

Market volatility results from these forecasting errors in predictable ways that fit with our empirical observations of stock prices. Stock returns are stochastic, rather than linear, reacting sharply to paradigm shifts. High-priced glamour stocks are more apt to experience unusually large negative price movements, usually after a string of negative news. The converse is true for value stocks. As a result, stocks with negative paradigms outperform stocks with positive paradigms because, when those paradigms are proven wrong, the stock prices move dramatically. These empirical truths have been widely validated.23

A more humanistic approach to finance suggests that the most intellectually honest approach—and the most profitable trading strategy—is to bet against the experts. This theory has the benefit of wide empirical support. Consider two natural conclusions that flow from a philosophy of unpredictability: preferring low-cost funds over high-cost funds and preferring contrarian strategies that buy out-of-favor value stocks. Evidence shows that there is a significant negative correlation between expenses paid to management companies and returns for investors.24

In direct contradiction to the capital asset pricing model, value stocks significantly outperform growth stocks.25 Large value stocks outperform large growth stocks by 0.26 percent per month controlling for CAPM, and small value stocks outperform small growth stocks by 0.78 percent per month controlling for CAPM. This is a significant and dramatic difference in return that stems entirely from betting on out-of-favor stocks that the experts dislike, and avoiding the glamorous, in-favor stocks that professional investors like.

These findings are consistent with an assumption of unpredictability. Those who try to predict fail, and the stocks of companies that are predicted to grow underperform the stocks of companies that are predicted not to grow. Growth is simply not predictable.26

Broader Implications

The man who would go on to become the youngest recipient of the Nobel Prize in economics, Kenneth Arrow, began his career during World War II in the Weather Division of the U.S. Army Air Force. The division was responsible for turning out long-range weather forecasts.Arrow ran an analysis of the forecasts and found that his group’s predictions failed to beat the null hypothesis of historical averages. He and his fellow officers submitted a series of memos to the commanding general suggesting that, in light of this finding, the group should be disbanded and the manpower reallocated.

After months of waiting in frustration for a response, they received a terse response from the general’s secretary. “The general is well aware that your division’s forecasts are worthless. However, they are required for planning purposes.”

Finance professionals rely on discounted cash flow models and capital asset pricing assumptions not because they are correct but because they are required for planning purposes. These tools lend social power to the excellent sheep of American society, the conventionally smart but dull and unimaginative strivers: the lawyers of the baby-boom generation and the MBAs of the millennial era.

These managerial capitalists are not trying to remake the world. They are neither craftsmen, pursuing a narrow discipline for the satisfaction of mastering a métier, nor are they entrepreneurs, pursuing bold ideas to satisfy a creative or competitive id. Rather, they are seeking to extract rents from “operating businesses” by taking on roles in private equity or “product management” where their prime value add will be the creation of multi-tab Excel models and beautifully formatted PowerPoint presentations.

Ironically, these theories were invented to avoid bubbles, to replace the volatility of markets with the predictability of an academic discipline. But corporate America’s embrace of empirically disproven theories speaks instead to a hollowness at the core—the prioritization of planning over purpose, of professional advancement over craftsmanship, and rent-seeking over entrepreneurship.

Harvard Business School and the Stanford Graduate School of Business are the Mecca and Medina of this new secular faith. The curriculum is divided between courses that flatter the vanity of the students (classes on leadership, life design, and interpersonal dynamics) and courses that promote empirically invalidated theories (everything with the word finance in the course title). Students can learn groupthink and central planning tools in one fell swoop.

Indeed, the problem of the business schools is so clear that a few clever wags on Wall Street now use the “Harvard MBA Indicator” as a tool to detect bubbles. If more than 30 percent of Harvard MBAs take jobs in finance, it is an effective sell signal for stocks.

Our capitalist economy offers every possible incentive for accuracy and the achievement of excellence. Why do people keep using bad theories that have failed in practice and have been academically invalidated? Not because these theories and methods produce better outcomes for society, but because they create better outcomes for the middle manager, creating a set of impenetrably complex models that mystify the common man and thus assure the value of the expert, of the MBA, of the two-years-at-an-investment-bank savant.

Active investment management does not work for investors because it was not designed to benefit them: it was designed to benefit the managers. The last decade of sclerotic economic growth has shown that, in many cases, corporate management teams are not working to benefit the shareholders, the employees, or anyone other than themselves.

XXX . V00 DEVELOPING NEW BUSINESS MODEL

Developing New Business Models

Most executives assume that creating a sustainable business model entails simply rethinking the customer value proposition and figuring out how to deliver a new one. However, successful models include novel ways of capturing revenues and delivering services in tandem with other companies. In 2008 FedEx came up with a novel business model by integrating the Kinko’s chain of print shops that it had acquired in 2004 with its document-delivery business. Instead of shipping copies of a document from, say, Seattle to New York, FedEx now asks customers if they would like to electronically transfer the master copy to one of its offices in New York. It prints and binds the document at an outlet there and can deliver copies anywhere in the city the next morning. The customer gets more time to prepare the material, gains access to better-quality printing, and can choose from a wide range of document formats that Fed-Ex provides. The document travels most of the way electronically and only the last few miles in a truck. FedEx’s costs shrink and its services become extremely eco-friendly.Some companies have developed new models just by asking at different times what their business should be. That’s what Waste Management, the $14 billion market leader in garbage disposal, did. Two years ago it estimated that some $9 billion worth of reusable materials might be found in the waste it carried to landfills each year. At about the same time, its customers, too, began to realize that they were throwing away money. Waste Management set up a unit, Green Squad, to generate value from waste. For instance, Green Squad has partnered with Sony in the United States to collect electronic waste that used to end up in landfills. Instead of being just a waste-trucking company, Waste Management is showing customers both how to recover value from waste and how to reduce waste.

New technologies provide start-ups with the ability to challenge conventional wisdom. Calera, a California start-up, has developed technology to extract carbon dioxide from industrial emissions and bubble it through seawater to manufacture cement. The process mimics that used by coral, which builds shells and reefs from the calcium and magnesium in seawater. If successful, Calera’s technology will solve two problems: Removing emissions from power plants and other polluting enterprises, and minimizing emissions during cement production. The company’s first cement plant is located in the Monterey Bay area, near the Moss Landing power plant, which emits 3.5 million tons of carbon dioxide annually. The key question is whether Calera’s cement will be strong enough when produced in large quantities to rival conventional Portland cement. The company is toying with a radical business model: It will give away cement to customers while charging polluters a fee for removing their emissions. Calera’s future is hard to predict, but its technology may well upend an established industry and create a cleaner world.

Developing a new business model requires exploring alternatives to current ways of doing business as well as understanding how companies can meet customers’ needs differently. Executives must learn to question existing models and to act entrepreneurially to develop new delivery mechanisms. As companies become more adept at this, the experience will lead them to the final stage of sustainable innovation, where the impact of a new product or process extends beyond a single market.

Creating Next-Practice Platforms

Next practices change existing paradigms. To develop innovations that lead to next practices, executives must question the implicit assumptions behind current practices. This is exactly what led to today’s industrial and services economy. Somebody once asked: Can we create a carriage that moves without horses pulling it? Can we fly like birds? Can we dive like whales? By questioning the status quo, people and companies have changed it. In like vein, we must ask questions about scarce resources: Can we develop waterless detergents? Can we breed rice that grows without water? Can biodegradable packaging help seed the earth with plants and trees?Sustainability can lead to interesting next-practice platforms. One is emerging at the intersection of the internet and energy management. Called the smart grid, it uses digital technology to manage power generation, transmission, and distribution from all types of sources along with consumer demand. The smart grid will lead to lower costs as well as the more efficient use of energy. The concept has been around for years, but the huge investments going into it today will soon make it a reality. The grid will allow companies to optimize the energy use of computers, network devices, machinery, telephones, and building equipment, through meters, sensors, and applications. It will also enable the development of cross-industry platforms to manage the energy needs of cities, companies, buildings, and households. Technology vendors such as Cisco, HP, Dell, and IBM are already investing to develop these platforms, as are utilities like Duke Energy, SoCal Edison, and Florida Power & Light.• • •

Two enterprise wide initiatives help companies become sustainable. One: When a company’s top management team decides to focus on the problem, change happens quickly. For instance, in 2005 General Electric’s CEO, Jeff Immelt, declared that the company would focus on tackling environmental issues. Since then every GE business has tried to move up the sustainability ladder, which has helped the conglomerate take the lead in several industries. Two: Recruiting and retaining the right kind of people is important. Recent research suggests that three-fourths of workforce entrants in the United States regard social responsibility and environmental commitment as important criteria in selecting employers. People who are happy about their employers’ positions on those issues also enjoy working for them. Thus companies that try to become sustainable may well find it easier to hire and retain talent.

Leadership and talent are critical for developing a low-carbon economy. The current economic system has placed enormous pressure on the planet while catering to the needs of only about a quarter of the people on it, but over the next decade twice that number will become consumers and producers. Traditional approaches to business will collapse, and companies will have to develop innovative solutions.

That will happen only when executives recognize a simple truth: Sustainability = Innovation.

Facing banks and financial institutions

- Not making enough money. Despite all of the headlines about banking profitability, banks and financial institutions still are not making enough return on investment, or the return on equity, that shareholders require.

- Consumer expectations. These days it’s all about the customer experience, and many banks are feeling pressure because they are not delivering the level of service that consumers are demanding, especially in regards to technology.

- Increasing competition from financial technology companies. Financial technology (FinTech) companies are usually start-up companies based on using software to provide financial services. The increasing popularity of FinTech companies is disrupting the way traditional banking has been done. This creates a big challenge for traditional banks because they are not able to adjust quickly to the changes – not just in technology, but also in operations, culture, and other facets of the industry.

- Regulatory pressure. Regulatory requirements continue to increase, and banks need to spend a large part of their discretionary budget on being compliant, and on building systems and processes to keep up with the escalating requirements.

What Will You Do In The Digital Economy?

By now, most executives are keenly aware that the digital economy can be either an opportunity or a threat. The question is not whether they should engage their business in it. Rather, it’s how to unleash the power of digital technology while maintaining a healthy business, leveraging existing IT investments, and innovating without disrupting themselves.

Yet most of those executives are shying away

Why aren’t more leaders willing to transform their business and seize the opportunity of our hyperconnected world? The answer is as simple as human nature. Innately, humans are uncomfortable with the notion of change. We even find comfort in stability and predictability. Unfortunately, the digital economy is none of these – it’s fast and always evolving.

Digital transformation is no longer an option – it’s the imperative

At this moment, we are witnessing an explosion of connections, data, and innovations. And even though this hyperconnectivity has changed the game, customers are radically changing the rules – demanding simple, seamless, and personalized experiences at every touch point.Billions of people are using social and digital communities to provide services, share insights, and engage in commerce. All the while, new channels for engaging with customers are created, and new ways for making better use of resources are emerging. It is these communities that allow companies to not only give customers what they want, but also align efforts across the business network to maximize value potential.

To seize the opportunities ahead, businesses must go beyond sensors, Big Data, analytics, and social media. More important, they need to reinvent themselves in a manner that is compatible with an increasingly digital world and its inhabitants (a.k.a. your consumers).

Here are a few companies that understand the importance of digital transformation – and are reaping the rewards:

- Under Armour: No longer is this widely popular athletic brand just selling shoes and apparel. They are connecting 38 million people on a digital platform. By focusing on this services side of the business, Under Armour is poised to become a lifestyle advisor and health consultant, using his product side as the enabler.

- Port of Hamburg: Europe’s second-largest port is keeping carrier trucks and ships productive around the clock. By fusing facility, weather, and traffic conditions with vehicle availability and shipment schedules, the Port increased container handling capacity by 178% without expanding its physical space.

- Haier Asia: This top-ranking multinational consumer electronics and home appliances company decided to disrupt itself before someone else did. The company used a two-prong approach to digital transformation to create a service-based model to seize the potential of changing consumer behaviors and accelerate product development.

- Uber: This startup darling is more than just a taxi service. It is transforming how urban logistics operates through a technology trifecta: Big Data, cloud, and mobile.

- American Society of Clinical Oncologists (ASCO): Even nonprofits can benefit from digital transformation. ASCO is transforming care for cancer patients worldwide by consolidating patient information with its CancerLinQ. By unlocking knowledge and value from the 97% of cancer patients who are not involved in clinical trials, healthcare providers can drive better, more data-driven decision making and outcomes.

It’s time to take action

During the SAP Executive Technology Summit at SAP TechEd on October 19–20, an elite group of CIOs, CTOs, and corporate executives will gather to discuss the challenges of digital transformation and how they can solve them. With the freedom of open, candid, and interactive discussions led by SAP Board Members and senior technology leadership, delegates will exchange ideas on how to get on the right path while leveraging their existing technology infrastructure.What Is Digital Transformation?

Achieving quantum leaps through disruption and using data in new contexts, in ways designed for more than just Generation Y — indeed, the digital transformation affects us all. It’s time for a detailed look at its key aspects.

Data finding its way into new settings

Archiving all of a company’s internal information until the end of time is generally a good idea, as it gives the boss the security that nothing will be lost. Meanwhile, enabling him or her to create bar graphs and pie charts based on sales trends – preferably in real time, of course – is even better.But the best scenario of all is when the boss can incorporate data from external sources. All of a sudden, information on factors as seemingly mundane as the weather start helping to improve interpretations of fluctuations in sales and to make precise modifications to the company’s offerings. When the gusts of autumn begin to blow, for example, energy providers scale back solar production and crank up their windmills. Here, external data provides a foundation for processes and decisions that were previously unattainable.

Quantum leaps possible through disruption

While these advancements involve changes in existing workflows, there are also much more radical approaches that eschew conventional structures entirely.“The aggressive use of data is transforming business models, facilitating new products and services, creating new processes, generating greater utility, and ushering in a new culture of management,” states Professor Walter Brenner of the University of St. Gallen in Switzerland, regarding the effects of digitalization.

Harnessing these benefits requires the application of innovative information and communication technology, especially the kind termed “disruptive.” A complete departure from existing structures may not necessarily be the actual goal, but it can occur as a consequence of this process.

Having had to contend with “only” one new technology at a time in the past, be it PCs, SAP software, SQL databases, or the Internet itself, companies are now facing an array of concurrent topics, such as the Internet of Things, social media, third-generation e-business, and tablets and smartphones. Professor Brenner thus believes that every good — and perhaps disruptive — idea can result in a “quantum leap in terms of data.”

Products and services shaped by customers

It has already been nearly seven years since the release of an app that enables customers to order and pay for taxis. Initially introduced in Berlin, Germany, mytaxi makes it possible to avoid waiting on hold for the next phone representative and pay by credit card while giving drivers greater independence from taxi dispatch centers. In addition, analyses of user data can lead to the creation of new services, such as for people who consistently order taxis at around the same time of day.“Successful models focus on providing utility to the customer,” Professor Brenner explains. “In the beginning, at least, everything else is secondary.”

In this regard, the private taxi agency Uber is a fair bit more radical. It bypasses the entire taxi industry and hires private individuals interested in making themselves and their vehicles available for rides on the Uber platform. Similarly, Airbnb runs a platform travelers can use to book private accommodations instead of hotel rooms.

Long-established companies are also undergoing profound changes. The German publishing house Axel Springer SE, for instance, has acquired a number of startups, launched an online dating platform, and released an app with which users can collect points at retail. Chairman and CEO Matthias Döpfner also has an interest in getting the company’s newspapers and other periodicals back into the black based on payment models, of course, but these endeavors are somewhat at odds with the traditional notion of publishing houses being involved solely in publishing.

The impact of digitalization transcends Generation Y

Digitalization is effecting changes in nearly every industry. Retailers will likely have no choice but to integrate their sales channels into an Omni channel approach. Seeking to make their data services as attractive as possible, BMW, Mercedes, and Audi have joined forces to purchase the digital map service HERE. Mechanical engineering companies are outfitting their equipment with sensors to reduce downtime and achieve further product improvements.“The specific potential and risks at hand determine how and by what means each individual company approaches the subject of digitalization,” Professor Brenner reveals. The resulting services will ultimately benefit every customer – not just those belonging to Generation Y, who present a certain basic affinity for digital methods.

“Think of cars that notify the service center when their brakes or drive belts need to be replaced, offer parking assistance, or even handle parking for you,” Brenner offers. “This can be a big help to elderly people in particular.”

Chief digital officers: team members, not miracle workers

Making the transition to the digital future is something that involves not only a CEO or a head of marketing or IT, but the entire company. Though these individuals do play an important role as proponents of digital models, it also takes more than just a chief digital officer alone.For Professor Brenner, appointing a single person to the board of a DAX company to oversee digitalization is basically absurd. “Unless you’re talking about Da Vinci or Leibnitz born again, nobody could handle such a task,” he states.

In Brenner’s view, this is a topic for each and every department, and responsibilities should be assigned much like on a soccer field: “You’ve got a coach and the players – and the fans, as well, who are more or less what it’s all about.”

Here, the CIO neither competes with the CDO nor assumes an elevated position in the process of digital transformation. Implementing new databases like SAP HANA or Hadoop, leveraging sensor data in both technical and commercially viable ways, these are the tasks CIOs will face going forward.

Human Skills for the Digital Future

Technology Evolves.

So Must We.

Uniquely Human Abilities

AI is excellent at automating routine knowledge work and generating new insights from existing data — but humans know what they don’t know.

There’s Nothing Soft About “Soft Skills”

To stay ahead of AI in an increasingly automated world, we need to start cultivating our most human abilities on a societal level. There’s nothing soft about these skills, and we can’t afford to leave them to chance.

We must revamp how and what we teach to nurture the critical skills of passion, curiosity, imagination, creativity, critical thinking, and persistence. In the era of AI, no one will be able to thrive without these abilities, and most people will need help acquiring and improving them.

Anything artificial intelligence does has to fit into a human-centered value system that takes our unique abilities into account. While we help AI get more powerful, we need to get better at being human.

XXX . V0000 Electronic Communication Systems Information Systems Security and control

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

XXX . V00000 Wide-Area Wireless Communication: Microwave, Satellite, 3G, 4G & WiMAX planning on moving to a new house on the outskirts of the city. You're a little worried about whether you will be able to get wireless Internet on your mobile phone service at your new home. So, you go to a local electronics store to get some advice. Here are some of the options: 2G, 3G, WiMAX, satellite phone and satellite Internet. So what does that all mean? Time for a closer look at wide-area wireless communications. Wireless CommunicationA wireless communication network refers to any type of network that establishes connections without cables. Wireless communications use electromagnetic (EM) waves that travel through the air. There are three main categories of wireless communication, based on how far the signal travels.In short-range wireless communication, the signal travels from a few centimeters to several meters. Examples include Bluetooth, infrared and ZigBee. In medium-range wireless communication, the signal travels up to 100 meters or so. WiFi is the best-known example. In wide-area wireless communication, the signal travels quite far, from several kilometers to several thousand kilometers. Examples of wide-area wireless communication systems are cellular communications, WiMAX and satellite communications. All of these use some form of microwave signals. MicrowavesMicrowaves are high-frequency signals in the 300 MHz to 300 GHz range. The signals can carry thousands of channels at the same time, making it a very versatile communication system. Microwaves are often used for point-to-point telecommunications, which means that the signal is focused into a narrow beam. You can typically recognize microwave-based communication systems by their use of a large antenna, often in a dish format. This is in contrast to radio signals, which are typically broadcast in all directions. Radio signals operate in the 3 Hz to 300 MHz range.Microwave signals are used for both satellite and ground-based communications. Many TV and telephone communications in the world are transmitted over long distances using microwave signals. They use a collection of ground stations and communication satellites. Ground stations are typically placed roughly 50 kilometers apart so they 'see' each other. Microwaves are also used in - you guessed it - microwave ovens. These microwaves, however, are quite different from those used in communication systems. First, the microwaves have a much higher power level so they can heat your food. Second, the signal doesn't carry any information because you're not trying to tell your lasagna something. Cellular CommunicationsMobile phones have become one of the most widely used wireless communication devices. You probably use one every day and don't think too much about how it actually works - except when it doesn't work.So, how do mobile phones work? A mobile phone or cell phone is very much like a two-way radio; you can wirelessly send and receive information. There are a few major components to the mobile phone system. These include cell towers, network processing centers and the actual phones themselves. Communications within a cellular network are made possible by cell towers. Your mobile phone establishes a wireless connection using electromagnetic waves with the nearest cell tower. This is a two-way connection, meaning you can both send and receive information. The cell tower has a wired connection to the telephone network. This makes it possible for you to connect with any other telephone in the world. So when you make a phone call from one cell phone to another, your phone connects to the cell tower, the cell tower connects to a network processing center, the network connects to another cell tower and that cell tower connects to the cell phone you are trying to reach. All this happens within a split second back and forth. As you move about your day, your wireless connection will jump from one cell tower to the next depending on where you are. This makes it possible to maintain a connection even if you travel great distances. The transmission distance of cell towers is in the order of several kilometers, so cell towers are placed close enough together for their signals to overlap. The area covered by a single cell tower is referred to as a 'cell' or 'site.' A large metropolitan area may have hundreds of cells to cover the entire region. If you are in a remote area far from the nearest cell tower, your phone will lose its connection to the network. These are the dreaded 'dead zones' without service. You may also lose service if you are in a location where signals have difficulty penetrating. This includes metal and concrete - and this is why you often lose reception in an elevator or in an underground parking garage. Anywhere else your phone doesn't work? You got it - in an airplane at 30,000 feet. The cellular network uses ground-based towers, so as soon as you get in the air, you're going to lose the signal. 1G, 2G, 3G and 4GMobile telephone systems have evolved through the various generations of technology. The first generation, or 1G technology, dates back to the 1980s and was based strictly on analog signals. The second generation, or 2G technology, was developed in the 1990s and used a completely digital system. A number of different 2G network technologies have been developed, including GSM (mostly used in Europe and Asia) and CDMA (mostly used in North America).Third generation, or 3G technology, was developed around the year 2000 and is able to carry a lot more data. In fact, 3G does not refer to a specific technology but to any network technology that provides a data transfer rate of at least 200 kilobits per second. A number of different 3G technologies exist, including upgraded versions of 2G technologies as well as some new ones. Each generation of technology uses different communication protocols. This includes details on which specific frequencies are being used, how many channels are involved and how information is converted between digital and analog. Different protocols means that with each generation, all the hardware needs to be upgraded, including the cell towers, network processing centers and the phones themselves. Different technologies within a single generation are also not always compatible, which means that you cannot assume you can use your 3G phone in a different country. As of 2013, fourth generation, or 4G technology, is under development, including HSPA+, LTE and WiMAX. 4G promises to deliver higher data transfer rates, approximately 10 times faster compared to 3G. These speeds are competitive with broadband Internet services available in homes and offices. While 4G is still under development, there has been a tremendous growth in data transfer over cellular networks. If you are like most smartphone users, you check email, upload photos and download videos. With around six billion mobile phones being used as of 2013, this means a whole lot of network traffic. WiMAXOne of the 4G technologies is WiMAX, or Worldwide Interoperability for Microwave Access. WiMAX is a standard for metropolitan area networks. It is similar to WiFi but works over greater distances and at higher transmission speeds. This means you need fewer base stations to cover the same area relative to WiFi.WiMAX is not only an example of a 4G cellular network technology; it can also provide direct Internet access to metropolitan areas. It can be used to reach areas that are currently not served by phone and cable companies. WiMAX consists of two components: towers and receivers. WiMAX towers are similar to cell towers, and the signals can cover a large area. WiMAX receivers can be installed into mobile computing devices, similar to a WiFi card or at fixed locations in homes and offices. XXX . V00000 The digital future of work: What skills will be needed? Robots have long carried out routine physical activities, but increasingly machines can also take on more sophisticated tasks. Experts provide advice on the skills people will need going forward. For an 18-year-old today, figuring out what kind of education and skills to acquire is an increasingly difficult undertaking. Machines are already conducting data mining for lawyers and writing basic press releases and news stories. In coming years and decades, the technology is sure to develop and encompass ever more human work activities. Yet machines cannot do everything. To be as productive as it could be, this new automation age will also require a range of human skills in the workplace, from technological expertise to essential social and emotional capabilities. In this video, one in a four-part series, experts from academia and industry join McKinsey partners to discuss the skills likely to be in demand and how young people today can prepare for a world in which people will interact ever more closely with machines. The interviews were filmed in April at the Digital Future of Work Summit in New York, which was hosted by the McKinsey Global Institute (MGI) and New York University’s Stern School of Business. Interviewees include NYU provost Katherine Fleming and professors Arun Sundararajan and Vasant Dhar; Tom Siebel, founder, chairman, and CEO of C3 IoT; Anne-Marie Slaughter, president and CEO of New America; Jeff Wald, cofounder and president of WorkMarket; Allen Blue, cofounder of LinkedIn; Mike Rosenbaum, CEO of Arena; along with MGI chairman and director James Manyika and MGI partners Michael Chui and Susan Lund. Interview transcriptX : For young people today, what’s clear is that they’re going to need to continue to learn throughout their lifetime. The idea that you get an education when you’re young and then you stop and you go and work for 40 or 50 years with that educational training and that’s it—that’s over. All of us are going to have to continue to adapt, get new skills, and possibly go back for different types of training and credentials. What’s very clear is that what our kids need to do is learn how to learn and become very flexible and adaptable.Y : The future of work that a college graduate is looking at today is so different from the future of work that I looked at when I was a college graduate. There’s far less structure, there’s far less predictability. You don’t know that you can invest in a particular set of capabilities today and that will be valuable in 20 years. We used to be able to say, “This is the career I’m going to choose.” That’s a difficult bet to make today with so much change. Z : More generally what I tell students is that it would help if you had the skills that are required to deal with information because those are the core skills that are necessary these days to help you learn new things. This ability to learn things on your own to some extent will be driven by the core skills you have and how you can handle and process information. P : The most important message is you need to prepare for yourself. If people are sitting back, waiting to be candidly taken care of by a welfare state, I don’t think that’s a very good answer. R : We found that, for example, in something like 60 percent of all occupations an average 30 percent of their work activities are automatable. What does that mean? We’re going to see more people working alongside machines, whether you call that artificial augmentation or augmented intelligence, but we’re going to see a lot more of that. That’s quite important because it raises our whole sense of imperatives. It means that more skill is going to be required to make the most of what the machines can do for the humans. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Workforce transitions in a time of automation ?

They’re going to need skills that they can only get by doing things. So every time they’re given the opportunity to do something, they should say yes to it, even if it doesn’t strike them initially as being exactly what they want to be doing.

Automation is happening, and it will bring substantial benefits to businesses and economies worldwide, but it won’t arrive overnight. A new McKinsey Global Institute report finds realizing automation’s full potential requires people and technology to work hand in hand.

Automation, digital platforms, and other innovations are changing the fundamental nature of work. Understanding these shifts can help policy makers, business leaders, and workers move forward.

Online talent platforms are increasingly connecting people to the right work opportunities. By 2025 they could add $2.7 trillion to global GDP, and begin to ameliorate many of the persistent problems in the world’s labor markets.

Automation is happening, and it will bring substantial benefits to businesses and economies worldwide, but it won’t arrive overnight. A new McKinsey Global Institute report finds realizing automation’s full potential requires people and technology to work hand in hand.

XXX . V000000 ELECTRONIC DATA INTERCHANGE

Electronic data interchange (EDI) is the use of computer and telecommunication technology to move data between or within organizations in a structured, computer retrievable data format that permits information to be transferred from a computer program in one location to a computer program in another location, without manual intervention. An example is the transmission of an electronic invoice from a supplier's invoicing software to a customer's accounts receivable software. This definition includes the direct transmission of data between locations, transmission using an intermediary such as a communication network, and the exchange of digital storage devices such as magnetic tapes, diskettes, and CD-ROMs.

EDI is one of the most important subsets of electronic commerce —the use of computer and telecommunication technology to facilitate the information exchange between two parties in a commercial transaction. The intent of all electronic commerce is to automate business processes. Some transactions can be completely paperless and move data from one computer application to another computer application. By strict definition EDI falls under this type of electronic commerce. Other electronic commerce transactions are also paperless but involve manual intervention. Examples are Internet transactions requiring one party to enter data manually. Electronic mail is another example of paperless but manual electronic commerce. Sometimes firms claim to be doing EDI when they are really performing a manual-to-computer transaction such as electronic order entry.

Another form of electronic commerce is based on physical media interacting with computers and telecommunications processes. Examples of this third type are facsimile transmission (paper plus telecommunications) and processes that involve information captured by bar coding, optical character recognition, and radio frequency tagging.

Exhibit I shows how EDI contrasts with facsimile transmission (fax) and electronic mail (e-mail). Fax is the transfer of totally unstructured data. With fax, a digitized image of a paper document is transmitted. While mail time delays are avoided, the receiver of a facsimile transmission would not be able to enter the image directly into a computer program without rekeying. E-mail also moves data electronically but is designed for person-to-person applications. It uses a free format rather than a structured format. A party receiving an e-mail purchase order, for example, would not likely be able to automatically read it into an order entry program, and would most likely have to rekey the information.

Exhibit 1

Contrasting EDI with Fax and E-Mail

Contrasting EDI with Fax and E-Mail

EDI has two important subsets, illustrated diagrammatically in Exhibit 2. Electronic Funds Transfer (EFT) is EDI between financial institutions. The result of an EFT transaction is the transfer of monetary value from one account to another. Examples of EFT systems in the United States are FedWire and Automated Clearing House (ACH) payments. FedWire is the same-day, real-time, electronic transfer of funds between two financial institutions using the communication network of the Federal Reserve. ACH transfers are batch-processed electronic transfers that settle in one or two business days. An example of an ACH transfer is the direct deposit of payroll offered by many firms to their employees. Using the ACH network, the originating bank sends electronic payment instructions to each receiving bank. Another application of the ACH system is direct debiting, which many consumers use to make mortgage, utility, and insurance payments.

Exhibit 2

Relationship between EDI, EFT and FEDI

Relationship between EDI, EFT and FEDI

Financial EDI (FEDI) is EDI between banks and their customers or between banks when there is not a value transfer. For example, a firm may receive electronic reports from its bank listing all checks received the previous day. A bank may also send its monthly statement to a firm using FEDI. Some firms send FEDI payment orders to their banks to initiate supplier payments.

BENEFITS OF EDI

EDI was developed to solve the problems inherent in paper-based transaction processing and in other forms of electronic communication. In solving these problems, EDI is a tool that enables organizations to reengineer information flows and business processes. Problems with the paper-based transaction system are:

- Time delays. Delays are caused primarily by two factors. Paper documents may take days to transport from one location to another. In addition, manual processing delays are caused by the need to key, file, retrieve, and compare data.

- Labor costs. In non-EDI systems, manual processing is required for data keying, document storing and retrieving, sorting, matching, reconciling, envelope stuffing, stamping, signing, etc. While automated equipment can help with some of these processes, most managers will agree that labor costs for document processing represents a significant proportion of their overhead. In general, labor-based processes are much more expensive than non-labor-intensive operations involving computers and telecommunications.

- Errors. Because information is keyed multiple times and documents are transported, stored, and retrieved by people, non-EDI systems tend to be error prone.

- Uncertainty. Uncertainty exists in two areas. First, paper transportation and other manual processing delays mean that the time the document is received is uncertain. Once a transaction is sent, the sender does not know when the transaction will be received nor when it will be processed. Second, the sender does not even know whether the transaction has been received at all nor whether the receiver agrees with what was sent in the transaction.

- High Inventories. Because of time delays and uncertainties in non EDI processing, inventories are often higher than necessary. Lead times with paper processing are long. In a manufacturing firm, it may be virtually impossible to achieve a just-in-time inventory system with the time delays inherent in non-EDI processing systems.

- Information Access. EDI permits user access to a vast amount of detailed transaction data—in a non-EDI environment this is possible only with great effort and time delay. Because EDI data is already in computer-retrievable form, it is subject to automated processing and analysis. Such information helps one retailer, for example, monitor sales of toys by model, color, and customer zip code. This enables the retailer to respond very quickly to changes in consumer taste.

INFRASTRUCTURE FOR EDI

To make EDI happen, four elements of infrastructure must exist: (1) format standards are required to facilitate automated processing by all users; (2) translation software is required to translate from a user's proprietary format for internal data storage into the generic external format and back again; (3) value-added networks are very helpful in solving the technical problems of sending information between computers; and (4) inexpensive microcomputers are required to bring all potential users—even small ones—into the market. It has only been in the past several years that all of these ingredients have fallen into place.

FORMAT STANDARDS.

To permit the efficient use of computers, information must be highly organized into a consistent data format. A format defines how information in a message is organized: what data goes where, what data is mandatory, what is optional, how many characters are permitted for each data field, how data fields are ordered, and what codes or abbreviations are permitted.Early EDI efforts in the 1960s used proprietary formats developed by one firm for exclusive use by its trading partners. This worked well until a firm wanted to exchange EDI documents with other firms who wanted to use their own formats. Since the different formats were not compatible, data exchange was difficult if not impossible.

To facilitate the widespread use of EDI, standard formats were developed so that an electronic message sent by one party could be understood by any receiver that subscribes to that format standard. In the United States the Transportation Data Coordinating Committee began in 1968 to design format standards for transportation documents. The first document was approved in 1975. This group pioneered the ideas that are used by all standards organizations today. North American standards are currently developed and maintained by a volunteer organization called ANSI (American National Standards Institute) X12 Accredited Standards Committee (or simply ANSI X12). The format for a document defined by ANSI Xl2 is broad enough to satisfy the needs of many different industries. Electronic documents (called transaction sets by ANSI X12) are typically of variable length and most of the information is optional. When a firm sends a standard EDI purchase order to another firm, it is possible for the receiving firm to pass the purchase order data through an EDI translation program directly to a business application, without manual intervention.

INDUSTRY CONVENTIONS.

To satisfy users from many different organizations with vastly different needs, the ANSI X12 standards must remain very generic. Some industries have developed their own subsets of the more generic EDI formats. These formats may be considered to be essentially customized formats of the more generic standard EDI formats. For example, the ANSI X12 standard defines two-digit codes for more than 400 units of measure. The automotive industry does not need nearly that many, so their industry convention documentation defines only a handful of units of measure. This makes EDI less confusing for implementers.TYPES OF STANDARDIZED DOCUMENTS.

There are currently generic standards for more than 300 types of transactions, including: purchase order, invoice, functional acknowledgment, purchase order acknowledgment, payment order, request for quote, insurance claim, inventory data, grade transcript, student loan data, freight invoice, bill of lading, lockbox receipt, load tender, library loan request, promotion announcement, advanced ship notice, material release, telephone bill, price/sales catalog, and claim tracer.EDIFACT STANDARDS.

Under the auspices of the United Nations, a format standard has been developed to reach a worldwide audience. These standards are called EDI for Administration, Commerce, and Transport (EDIFACT). They are similar in many respects to ANSI Xl2 standards but are accepted by a larger number of countries. In the future, all new ANSI X12 EDI documents will be developed using the EDIFACT format.TRANSLATION SOFTWARE.

Translation software makes EDI work by translating data from the sending firm's internal format into a generic EDI format. Translation software also receives a sender's EDI message and translates it from the generic standard into the receiver's internal format. There are currently translation software packages for almost all types of computers and operating systems.VALUE-ADDED NETWORKS (VANS).

When firms first began using EDI, most communications of EDI documents were directly between trading partners. Unfortunately, direct computer to-computer communications requires that both firms (1) use similar communication protocols, (2) have the same transmission speed, (3) have phone lines available at the same time, and (4) have compatible computer hardware. If these conditions are not met, then communication becomes difficult if not impossible. A value-added network (VAN) can solve these problems by providing an electronic mailbox service. By using a VAN, an EDI sender need only learn to send and receive messages to/from one party: the VAN. Since a VAN provides a very flexible computer interface, it can talk to virtually any type of computer. This means that to do EDI with hundreds of trading partners, an organization has to talk to only one party.VANs also provide a secure interface between trading partners. Since trading partners send EDI messages only through the VAN, there is no fear that a trading partner may dip into sensitive information stored on the computer system nor that a trading partner nay send a computer virus to the other partners.

One of the most important recent developments in EDI is the use of the Internet as the delivery network for EDI transactions. Since the Internet is so widely available, even most smaller firms have access to and familiarity with the use of browsers. Some service providers are using browser technology to permit trading partners to enter data into forms on web pages. The data can then be translated into EDI format and transmitted to the receiving party. While not strictly computer-to-computer, this process allows a receiver to make greater use of EDI on their side of the transaction.

INEXPENSIVE COMPUTERS.

The fourth building block of EDI is inexpensive computers that permit even small firms to implement EDI. Since microcomputers are now so prevalent, it is possible for firms of all sizes to deal with each other using EDI.EXAMPLES OF EDI

The Bergen Brunswig Drug Company, a wholesale pharmaceutical distributor in Orange, California, is one of the most successful companies in using EDI for many of its business processes. To generate an order to Bergen Brunswig, a customer (pharmacist) uses a handheld bar code scanner to capture the UPC (Uniform Product Code) number on a shelf label for a product to be ordered. The pharmacist enters the quantity desired into a keypad on the scanner and moves onto the next item. All items in the pharmacy can be scanned in only a few minutes. A microcomputer next reads the information contained in the scanner and an electronic order is prepared for the pharmacist's review. The order is sent via EDI to a Bergen Brunswig distribution center where the order is analyzed and resequenced to match the product location in the distribution center. Within five hours, the order is delivered to the pharmacy. Bergen Brunswig has been able to eliminate all order takers, reduce errors to near zero, fulfill orders faster, reduce overhead costs, and build customer loyalty. The company also uses EDI for sending purchase orders to pharmaceutical manufacturers, receiving invoices, and handling charge backs.

The JCPenney Company has an operating center in Salt Lake City, Utah, which uses EDI to receive almost all of its invoices from suppliers. The result has been substantial savings in terms of personnel costs (four processing centers were combined into one and several hundred people who did manual processing were no longer needed), a reduction in errors, faster matching of invoice and purchase order, more timely payments, and a reduction in paper storage requirements.

U.S. auto manufacturers are also extensive users of EDI. Chrysler, as illustrated in Figure 3, has applied EDI to reengineer its manufacturing processes. Once a contract has been negotiated with a parts supplier, Chrysler sends the supplier weekly electronic material releases specifying the intended use of parts over an eight-week horizon. Several days before the parts are needed, Chrysler sends an EDI delivery order to the supplier detailing precisely how many parts are needed for delivery on a certain date, where the parts are to be delivered, what bar coding is to be put on the containers, and when delivery is expected. Some suppliers are told how to sequence the parts on the truck for most effective unloading. After the supplier loads the parts, an EDI advanced shipping notice is sent to Chrysler verifying that the delivery is on the way. Chrysler scans the parts in as they arrive and may send an electronic discrepancy report if there are problems. Payments are often made electronically on a settlement date specified in the contract. No invoice is used in this reengineered process. In this environment Chrysler needs very little inventory and, in fact, has been able to shave approximately $ 1 billion from its parts inventory.

Exhibit 3

EDI in the Automotive Industry

EDI in the Automotive Industry

Use of EDI is spreading to many different types of organizations. The insurance industry is beginning to use EDI for health care claims, procedure authorization, and payments. Universities are using EDI for sending grade transcripts, interlibrary material requests, and student loan information. Retailers are sending EDI inventory data to suppliers and charging them with oversight of inventory levels and shipment initiation. The federal government and most states are now using EDI to collect tax filing information.

STATUS OF EDI

EDI appears to be entering into a rapid growth phase. According to an extensive market survey completed by the EDI Group, a division of Thomson EC Resources, well over 60 percent of U.S. firms with more than 5,000 employees are using EDI. Over the past several years there has been an enormous increase in the infrastructure supporting EDI, including seminars and conferences, books, periodicals, consultants, and software companies. From its current growth patterns, EDI is poised to become more and more important as a data communication tool that enables organizations to more efficiently design internal processes and external interactions with trading partners.

ELECTRONIC MAIL

From its roots as an obscure mode of communication among computer hobbyists, academics, and military personnel, e-mail use has burgeoned to a medium of mass communication. According to published estimates from International Data Corp., a technology market research firm, as of 1998 there were 82 million personal and business e-mail accounts in the United States. For comparison, that figure was equal to half the number of telephones in use, an impressive proportion given that e-mail has been in existence only a quarter as long as the telephone.

E-mail's late 1960s inception came about from the work of Ray Tomlinson, a computer scientist working for a defense contractor. Tomlinson's work was for the U.S. Defense Department's Arpanet, the project that later spawned the Internet.

E-MAIL TECHNOLOGY

E-mail technology for the Internet (as opposed to closed private systems) follows a number of universal standards as codified by the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) and the International Organization for Standardization (ISO). These standards help ensure that e-mail, like Internet communications in general, is not bounded by platform or geography.

An e-mail message is essentially one or more files being copied between computers on a network such as the Internet. This transfer of files is automated and managed by a variety of computer programs working in consort. A simple e-mail may be a single text file; if special formatting, graphics, or attachments are used in the message, multiple binary files or encoded Hypertext Markup Language (HTML) files may be transmitted in a single e-mail message.

A typical e-mail system consists of at least three software components with supporting hardware:

- the user's e-mail application

- a message transfer agent or engine

- a message store

The message transfer agent (MTA), also called a mail engine, is behind-the-scenes software that runs on a mail server, the computer(s) dedicated to sorting and routing e-mail in a network. The MTA determines how incoming and outgoing messages should be routed. Thus, if a message is sent from one internal corporate user to another, the MTA normally routes the e-mail within the corporate system without sending it through the Internet. If, however, a message is intended for a user outside the organization, the mail server transmits the file to an external gateway or a public Internet backbone router that will, in turn, deliver the message to the recipient's system. This is a simplification, as a message may actually be passed through several intermediate computers on the Internet before reaching its destination.

The message store is the software and hardware that handles incoming mail once the MTA has determined that mail belongs to a specific user on the system. The store may be configured to work in different ways, but, in essence it is user-specific directory space on a network server in which unread incoming messages are stored for future retrieval by the e-mail applications. This is where, for instance, e-mail sent overnight sits until the recipient turns on his computer the next day and opens his e-mail program. The software configuring the message store may automatically delete copies of the messages once they are downloaded to the user's computer or it may archive them. Message stores are also capable of automatically categorizing mail and performing other mail-management tasks.

E-MAIL SECURITY AND PRIVACY

In spite of all its conveniences, e-mail is still a notoriously insecure method of communication, particularly in corporate environments. Technologically, most of the security encryption tools and other privacy safeguards available on the mass market are easily broken by experienced hackers. It is even simpler to forge an e-mail from someone using their address. Furthermore, what many employees don't realize is that their employers can—and do—legally monitor e-mail on the corporate system. A series of court cases have arisen from such activities, and the courts have upheld companies' rights to control information transmitted on their computer systems. Common information systems practices such as scheduled backups of network data can make the process of e-mail monitoring even easier for employers. Employer e-mail surveillance has already taken on seemingly excessive zeal: one company allegedly reported an employee to the police for sending a fellow employee an e-mail describing how he was forced to put a pet to sleep; the employer misunderstood the e-mail as a death threat against a coworker.

In response to such circumstances, some observers have concluded that corporate e-mail users should assume there is no privacy in their e-mail communications. A representative from a well-known Internet applications company likened it to sending a postcard in conventional mail—the entire message is visible to anyone who chooses to look.

CORPORATE E-MAIL POLICIES