X . I Skyscraper

A skyscraper is a tall, continuously habitable building having multiple floors. When the term was originally used in the 1880s it described a building of 10 to 20 floors but now describes one of at least 40–50 floors. Mostly designed for office, commercial and residential uses, a skyscraper can also be called a high-rise, but the term "skyscraper" is often used for buildings higher than 100 m (328 ft).For buildings above a height of 300 m (984 ft), the term "supertall" can be used, while skyscrapers reaching beyond 600 m (1,969 ft) are classified as "megatall".

One common feature of skyscrapers is having a steel framework that supports curtain walls. These curtain walls either bear on the framework below or are suspended from the framework above, rather than resting on load-bearing walls of conventional construction. Some early skyscrapers have a steel frame that enables the construction of load-bearing walls taller than of those made of reinforced concrete.

Modern skyscrapers' walls are not load-bearing, and most skyscrapers are characterized by large surface areas of windows made possible by steel frames and curtain walls. However, skyscrapers can have curtain walls that mimic conventional walls with a small surface area of windows. Modern skyscrapers often have a tubular structure, and are designed to act like a hollow cylinder to resist wind, seismic, and other lateral loads. To appear more slender, allow less wind exposure, and transmit more daylight to the ground, many skyscrapers have a design with setbacks, which are sometimes also structurally required.

The term "skyscraper" was first applied to buildings of steel framed construction of at least 10 stories in the late 19th century, a result of public amazement at the tall buildings being built in major cities like Chicago, New York City, Philadelphia, Detroit, and St. Louis.[4] The first steel-frame skyscraper was the Home Insurance Building (originally 10 stories with a height of 42 m or 138 ft) in Chicago, Illinois in 1885. Some point to Philadelphia's 10-story Jayne Building (1849–50) as a proto-skyscraper, or to New York's seven-floor Equitable Life Building (New York City), built in 1870, for its innovative use of a kind of skeletal frame, but such designation depends largely on what factors are chosen. Even the scholars making the argument find it to be purely academic.

The structural definition of the word skyscraper was refined later by architectural historians, based on engineering developments of the 1880s that had enabled construction of tall multi-story buildings. This definition was based on the steel skeleton—as opposed to constructions of load-bearing masonry, which passed their practical limit in 1891 with Chicago's Monadnock Building

What is the chief characteristic of the tall office building? It is lofty. It must be tall. The force and power of altitude must be in it, the glory and pride of exaltation must be in it. It must be every inch a proud and soaring thing, rising in sheer exaltation that from bottom to top it is a unit without a single dissenting line.

-

-

- —Louis Sullivan's The Tall Office Building Artistically Considered (1896)

-

The word skyscraper often carries a connotation of pride and achievement. The skyscraper, in name and social function, is a modern expression of the age-old symbol of the world center or axis mundi: a pillar that connects earth to heaven and the four compass directions to one another.[9]

A loose convention of some in the United States and Europe draws the lower limit of a skyscraper at 150 m (490 ft).[10] But the term is also often used for buildings taller than 100 m (330 ft).[2]

The tallest building in ancient times was the 146 m (479 ft) Great Pyramid of Giza in ancient Egypt, built in the 26th century BC. It was not surpassed in height for thousands of years, the 160 m (520 ft) Lincoln Cathedral have exceeded it in 1311–1549, before central spire collapsed.[11] The latter in turn was not surpassed until the 555-foot (169 m) Washington Monument in 1884. However, being uninhabited, none of these structures actually comply with the modern definition of a skyscraper.

High-rise apartments flourished in classical antiquity. Ancient Roman insulae in imperial cities reached 10 and more stories.[12] Beginning with Augustus (r. 30 BC-14 AD), several emperors attempted to establish limits of 20–25 m for multi-story buildings, but met with only limited success.[13][14] Lower floors were typically occupied by shops or wealthy families, the upper rented to the lower classes.[12] Surviving Oxyrhynchus Papyri indicate that seven-story buildings existed in provincial towns such as in 3rd century AD Hermopolis in Roman Egypt.[15]

The skylines of many important medieval cities had large numbers of high-rise urban towers, built by the wealthy for defense and status. The residential Towers of 12th century Bologna numbered between 80 and 100 at a time, the tallest of which is the 97.2 m (319 ft) high Asinelli Tower. A Florentine law of 1251 decreed that all urban buildings be immediately reduced to less than 26 m.[16] Even medium-sized towns of the era are known to have proliferations of towers, such as the 72 up to 51 m height in San Gimignano.[16]

The medieval Egyptian city of Fustat housed many high-rise residential buildings, which Al-Muqaddasi in the 10th century described as resembling minarets. Nasir Khusraw in the early 11th century described some of them rising up to 14 stories, with roof gardens on the top floor complete with ox-drawn water wheels for irrigating them.[17] Cairo in the 16th century had high-rise apartment buildings where the two lower floors were for commercial and storage purposes and the multiple stories above them were rented out to tenants.[18] An early example of a city consisting entirely of high-rise housing is the 16th-century city of Shibam in Yemen. Shibam was made up of over 500 tower houses,[19] each one rising 5 to 11 stories high,[20] with each floor being an apartment occupied by a single family. The city was built in this way in order to protect it from Bedouin attacks.[19] Shibam still has the tallest mudbrick buildings in the world, with many of them over 30 m (98 ft) high.[21]

An early modern example of high-rise housing was in 17th-century Edinburgh, Scotland, where a defensive city wall defined the boundaries of the city. Due to the restricted land area available for development, the houses increased in height instead. Buildings of 11 stories were common, and there are records of buildings as high as 14 stories. Many of the stone-built structures can still be seen today in the old town of Edinburgh. The oldest iron framed building in the world, although only partially iron framed, is The Flaxmill (also locally known as the "Maltings"), in Shrewsbury, England. Built in 1797, it is seen as the "grandfather of skyscrapers", since its fireproof combination of cast iron columns and cast iron beams developed into the modern steel frame that made modern skyscrapers possible. In 2013 funding was confirmed to convert the derelict building into offices.[22]

Oriel Chambers, Liverpool. The world's first glass curtain walled building. The stone mullions are decorative.

Early skyscrapers

The architect, Major William Le Baron Jenney, created a load-bearing structural frame. In this building, a steel frame supported the entire weight of the walls, instead of load-bearing walls carrying the weight of the building. This development led to the "Chicago skeleton" form of construction. In addition to the steel frame, the Home Insurance Building also utilized fireproofing, elevators, and electrical wiring, key elements in most skyscrapers today.[28]

Burnham and Root's 45 m (148 ft) Rand McNally Building in Chicago, 1889, was the first all-steel framed skyscraper,[29] while Louis Sullivan's 41 m (135 ft) Wainwright Building in St. Louis, Missouri, 1891, was the first steel-framed building with soaring vertical bands to emphasize the height of the building and is therefore considered to be the first early skyscraper.

Most early skyscrapers emerged in the land-strapped areas of Chicago and New York City toward the end of the 19th century. A land boom in Melbourne, Australia between 1888 and 1891 spurred the creation of a significant number of early skyscrapers, though none of these were steel reinforced and few remain today. Height limits and fire restrictions were later introduced. London builders soon found building heights limited due to a complaint from Queen Victoria, rules that continued to exist with few exceptions until the 1950s.

Concerns about aesthetics and fire safety had likewise hampered the development of skyscrapers across continental Europe for the first half of the twentieth century. Some notable exceptions are the 43 m (141 ft) tall 1898 Witte Huis (White House) in Rotterdam; the Royal Liver Building in Liverpool, completed in 1911 and 90 m (300 ft) high;[30] the 57 m (187 ft) tall 1924 Marx House in Düsseldorf, Germany; the 61 m (200 ft) Kungstornen (Kings' Towers) in Stockholm, Sweden, which were built 1924–25,[31] the 89 m (292 ft) Edificio Telefónica in Madrid, Spain, built in 1929; the 87.5 m (287 ft) Boerentoren in Antwerp, Belgium, built in 1932; the 66 m (217 ft) Prudential Building in Warsaw, Poland, built in 1934; and the 108 m (354 ft) Torre Piacentini in Genoa, Italy, built in 1940.

After an early competition between Chicago and New York City for the world's tallest building, New York took the lead by 1895 with the completion of the 103 m (338 ft) long American Surety Building, leaving New York with the title of the world's tallest building for many years.

Modern skyscrapers

The Flatiron building completed in 1902 in New York City

The Empire State Building in New York City. Completed in 1931, it was the tallest building in the world for nearly 40 years.

From the 1930s onwards, skyscrapers began to appear around the world—such as in Latin America (such as São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, Buenos Aires, Santiago, Lima, Caracas, Bogotá, Panama City, Mexico City, Monterrey) and in Asia (Tokyo, Shanghai, Hong Kong, Manila, Jakarta, Singapore, Mumbai, Seoul, Kuala Lumpur, Taipei, Bangkok).

Immediately after World War II, the Soviet Union planned eight massive skyscrapers, seven of which were built by 1953, dubbed the "Seven Sisters of Moscow". The Building of Moscow State University was the tallest building in Europe in 1953–1990. Other skyscrapers in the style of Socialist Classicism were erected in East Germany (Frankfurter Tor), Poland (PKiN), Ukraine (Hotel Ukrayina), Latvia (Academy of Sciences) and other countries. The western countries of Europe also began to permit taller skyscrapers than before WW2, such as Madrid during the 1950s (Gran Vía). Finally, skyscrapers also began to be constructed in cities of Africa, the Middle East and Oceania (mainly Australia) from the late 1950s on.

Skyscraper projects after World War II typically rejected the classical designs of the early skyscrapers, instead embracing the uniform international style; many older skyscrapers were redesigned to suit contemporary tastes or even demolished—such as New York's Singer Building, once the world's tallest skyscraper.

German architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe became one of the world's most renowned architects in the second half of the 20th century. He conceived of the glass façade skyscraper[32] and, along with Norwegian Fred Severud,[33] he designed the Seagram Building in 1958, a skyscraper that is often regarded as the pinnacle of the modernist high-rise architecture.[34]

After the Great Depression skyscrapers construction suffered a hiatus for over thirty years due to economic problems. A revival occurred with structural innovations that transformed the industry,[35] making it possible for people to live and work in "cities in the sky".[36]

In the early 1960s structural engineer Fazlur Rahman Khan, considered the "father of tubular designs" for high-rises,[37] realized that the dominating rigid steel frame structure was not the only system apt for tall buildings, marking a new era of skyscraper construction in terms of multiple structural systems.[38] His central innovation in skyscraper design and construction was the concept of the "tube" structural system, including the "framed tube", "trussed tube", and "bundled tube".[39] These systems allow greater economic efficiency,[40] and also allow skyscrapers to take on various shapes, no longer needing to be rectangular and box-shaped.[41] The first building to employ the tube structure was the Chestnut De-Witt apartment building.[35] Over the next fifteen years, many towers were built by Fazlur Rahman Khan and the "Second Chicago School",[42] including the massive 442 m (1,450 ft) Willis Tower.[43] Other pioneers of this field include Hal Iyengar and William LeMessurier.

Modern building practices regarding supertall structures have led to the study of "vanity height".[44][45] Vanity height, according to the CTBUH, is the distance between the highest floor and its architectural top (excluding antennae, flagpole or other functional extensions). Vanity height first appeared in New York City skyscrapers as early as the 1920s and 1930s but supertall buildings have relied on such uninhabitable extensions for on average 30% of their height, raising potential definitional and sustainability issues.[46][47][48] The current era of skyscrapers focuses on sustainability, its built and natural environments, including the performance of structures, types of materials, construction practices, absolute minimal use of materials and natural resources, energy within the structure, and a holistically integrated building systems approach. LEED is a current green building standard.[49]

Architecturally, with the movements of Postmodernism, New Urbanism and New Classical Architecture, that established since the 1980s, a more classical approach came back to global skyscraper design, that remains popular today.[50] Examples are the Wells Fargo Center, NBC Tower, Parkview Square, 30 Park Place, the Messeturm, the iconic Petronas Towers and Jin Mao Tower.

Other contemporary styles and movements in skyscraper design include organic, sustainable, neo-futurist, structuralist, high-tech, deconstructivist, blob, digital, streamline, novelty, critical regionalist, vernacular, Neo Art Deco and neo-historist, also known as revivalist.

3 September is the global commemorative day for skyscrapers, called "Skyscraper Day".[51]

New York City developers competed among themselves, with successively taller buildings claiming the title of "world's tallest" in the 1920s and early 1930s, culminating with the completion of the 318.9 m (1,046 ft) Chrysler Building in 1930 and the 443.2 m (1,454 ft) Empire State Building in 1931, the world's tallest building for forty years. The first completed 417 m (1,368 ft) tall World Trade Center tower became the world's tallest building in 1972. However, it was overtaken by the Sears Tower (now Willis Tower) in Chicago within two years. The 442 m (1,450 ft) tall Sears Tower stood as the world's tallest building for 24 years, from 1974 until 1998, until it was edged out by 452 m (1,483 ft) Petronas Twin Towers in Kuala Lumpur, which held the title for six years.

Design and construction

Modern Skyscrapers in Downtown Los Angeles

One common feature of skyscrapers is a steel framework from which curtain walls are suspended, rather than load-bearing walls of conventional construction. Most skyscrapers have a steel frame that enables them to be built taller than typical load-bearing walls of reinforced concrete. Skyscrapers usually have a particularly small surface area of what are conventionally thought of as walls. Because the walls are not load-bearing most skyscrapers are characterized by surface areas of windows made possible by the concept of steel frame and curtain wall. However, skyscrapers can also have curtain walls that mimick conventional walls and have a small surface area of windows.

The concept of a skyscraper is a product of the industrialized age, made possible by cheap fossil fuel derived energy and industrially refined raw materials such as steel and concrete. The construction of skyscrapers was enabled by steel frame construction that surpassed brick and mortar construction starting at the end of the 19th century and finally surpassing it in the 20th century together with reinforced concrete construction as the price of steel decreased and labour costs increased.

The steel frames become inefficient and uneconomic for supertall buildings as usable floor space is reduced for progressively larger supporting columns.[52] Since about 1960, tubular designs have been used for high rises. This reduces the usage of material (more efficient in economic terms – Willis Tower uses a third less steel than the Empire State Building) yet allows greater height. It allows fewer interior columns, and so creates more usable floor space. It further enables buildings to take on various shapes.

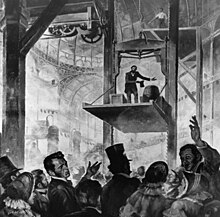

Elevators are characteristic to skyscrapers. In 1852 Elisha Otis introduced the safety elevator, allowing convenient and safe passenger movement to upper floors. Another crucial development was the use of a steel frame instead of stone or brick, otherwise the walls on the lower floors on a tall building would be too thick to be practical. Today major manufacturers of elevators include Otis, ThyssenKrupp, Schindler, and KONE.

Advances in construction techniques have allowed skyscrapers to narrow in width, while increasing in height. Some of these new techniques include mass dampers to reduce vibrations and swaying, and gaps to allow air to pass through, reducing wind shear.[53]

Basic design considerations

Good structural design is important in most building design, but particularly for skyscrapers since even a small chance of catastrophic failure is unacceptable given the high price. This presents a paradox to civil engineers: the only way to assure a lack of failure is to test for all modes of failure, in both the laboratory and the real world. But the only way to know of all modes of failure is to learn from previous failures. Thus, no engineer can be absolutely sure that a given structure will resist all loadings that could cause failure, but can only have large enough margins of safety such that a failure is acceptably unlikely. When buildings do fail, engineers question whether the failure was due to some lack of foresight or due to some unknowable factor.Loading and vibration

The load a skyscraper experiences is largely from the force of the building material itself. In most building designs, the weight of the structure is much larger than the weight of the material that it will support beyond its own weight. In technical terms, the dead load, the load of the structure, is larger than the live load, the weight of things in the structure (people, furniture, vehicles, etc.). As such, the amount of structural material required within the lower levels of a skyscraper will be much larger than the material required within higher levels. This is not always visually apparent. The Empire State Building's setbacks are actually a result of the building code at the time (1916 Zoning Resolution), and were not structurally required. On the other hand, John Hancock Center's shape is uniquely the result of how it supports loads. Vertical supports can come in several types, among which the most common for skyscrapers can be categorized as steel frames, concrete cores, tube within tube design, and shear walls.The wind loading on a skyscraper is also considerable. In fact, the lateral wind load imposed on super-tall structures is generally the governing factor in the structural design. Wind pressure increases with height, so for very tall buildings, the loads associated with wind are larger than dead or live loads.

Other vertical and horizontal loading factors come from varied, unpredictable sources, such as earthquakes.

Steel frame

By 1895, steel had replaced cast iron as skyscrapers' structural material. Its malleability allowed it to be formed into a variety of shapes, and it could be riveted, ensuring strong connections.[54] The simplicity of a steel frame eliminated the inefficient part of a shear wall, the central portion, and consolidated support members in a much stronger fashion by allowing both horizontal and vertical supports throughout. Among steel's drawbacks is that as more material must be supported as height increases, the distance between supporting members must decrease, which in turn increases the amount of material that must be supported. This becomes inefficient and uneconomic for buildings above 40 stories tall as usable floor spaces are reduced for supporting column and due to more usage of steel.[52]Tube structural systems

The Willis Tower in Chicago showing the bundled tube frame design

The tubular systems are fundamental to tall building design. Most buildings over 40-stories constructed since the 1960s now use a tube design derived from Khan's structural engineering principles, examples including the construction of the World Trade Center, Aon Center, Petronas Towers, Jin Mao Building, and most other supertall skyscrapers since the 1960s. The strong influence of tube structure design is also evident in the construction of the current tallest skyscraper, the Burj Khalifa.

Trussed tube and X-bracing

Changes of structure with height. The tubular systems are fundamental for super tall buildings.

The John Hancock Center was far more efficient than earlier steel-frame structures. Where the Empire State Building (1931), required about 206 kilograms of steel per square metre and Chase Manhattan Bank Building (1961) required 275, the John Hancock Center required only 145.[40] The trussed tube concept was applied to many later skyscrapers, including the Onterie Center, Citigroup Center and Bank of China Tower.[58]

Bundled tube

An important variation on the tube frame is the "bundled tube", which uses several interconnected tube frames. The Willis Tower in Chicago used this design, employing nine tubes of varying height to achieve its distinct appearance. The bundled tube structure meant that "buildings no longer need be boxlike in appearance: they could become sculpture."[41]The elevator conundrum

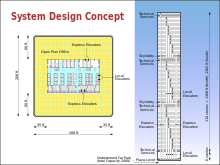

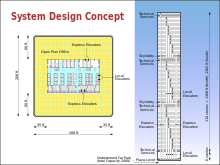

The invention of the elevator was a precondition for the invention of skyscrapers, given that most people would not (or could not) climb more than a few flights of stairs at a time. The elevators in a skyscraper are not simply a necessary utility, like running water and electricity, but are in fact closely related to the design of the whole structure: a taller building requires more elevators to service the additional floors, but the elevator shafts consume valuable floor space. If the service core, which contains the elevator shafts, becomes too big, it can reduce the profitability of the building. Architects must therefore balance the value gained by adding height against the value lost to the expanding service core.[59]Many tall buildings use elevators in a non-standard configuration to reduce their footprint. Buildings such as the former World Trade Center Towers and Chicago's John Hancock Center use sky lobbies, where express elevators take passengers to upper floors which serve as the base for local elevators. This allows architects and engineers to place elevator shafts on top of each other, saving space. Sky lobbies and express elevators take up a significant amount of space, however, and add to the amount of time spent commuting between floors.

Other buildings, such as the Petronas Towers, use double-deck elevators, allowing more people to fit in a single elevator, and reaching two floors at every stop. It is possible to use even more than two levels on an elevator, although this has never been done. The main problem with double-deck elevators is that they cause everyone in the elevator to stop when only people on one level need to get off at a given floor.

Buildings with sky lobbies include the World Trade Center, Petronas Twin Towers and Taipei 101. The 44th-floor sky lobby of the John Hancock Center also featured the first high-rise indoor swimming pool, which remains the highest in America.

Economic rationale

Skyscrapers are usually situated in city centers where the price of land is high. Constructing a skyscraper becomes justified if the price of land is so high that it makes economic sense to build upwards as to minimize the cost of the land per the total floor area of a building. Thus the construction of skyscrapers is dictated by economics and results in skyscrapers in a certain part of a large city unless a building code restricts the height of buildings.Skyscrapers are rarely seen in small cities and they are characteristic of large cities, because of the critical importance of high land prices for the construction of skyscrapers. Usually only office, commercial and hotel users can afford the rents in the city center and thus most tenants of skyscrapers are of these classes. Some skyscrapers have been built in areas where the bedrock is near surface, because this makes constructing the foundation cheaper, for example this is the case in Midtown Manhattan and Lower Manhattan, in New York City, but not in-between these two parts of the city.

Today, skyscrapers are an increasingly common sight where land is expensive, as in the centers of big cities, because they provide such a high ratio of rentable floor space per unit area of land.

One problem with skyscrapers is car parking. In the largest cities most people commute via public transport, but for smaller cities a lot of parking spaces are needed. Multi-storey car parks are impractical to build very tall, so a lot of land area is needed.

There may be a correlation between skyscraper construction and great income inequality but this has not been conclusively proved

The amount of steel, concrete and glass needed to construct a single skyscraper is large, and these materials represent a great deal of embodied energy. Skyscrapers are thus energy intensive buildings, but skyscrapers have a long lifespan, for example the Empire State Building in New York City, United States completed in 1931 and is still in active use.

Skyscrapers have considerable mass, which means that they must be built on a sturdier foundation than would be required for shorter, lighter buildings. Building materials must also be lifted to the top of a skyscraper during construction, requiring more energy than would be necessary at lower heights. Furthermore, a skyscraper consumes a lot of electricity because potable and non-potable water have to be pumped to the highest occupied floors, skyscrapers are usually designed to be mechanically ventilated, elevators are generally used instead of stairs, and natural lighting cannot be utilized in rooms far from the windows and the windowless spaces such as elevators, bathrooms and stairwells.

Skyscrapers can be artificially lighted and the energy requirements can be covered by renewable energy or other electricity generation of low greenhouse gas emissions. Heating and cooling of skyscrapers can be efficient, because of centralized HVAC systems, heat radiation blocking windows and small surface area of the building. There is Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) certification for skyscrapers. For example, the Empire State Building received a gold Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design rating in September 2011 and the Empire State Building is the tallest LEED certified building in the United States,[62] proving that skyscrapers can be environmentally friendly. Also the 30 St Mary Axe in London, the United Kingdom is an environmentally friendly skyscraper.

In the lower levels of a skyscraper a larger percentage of the building cross section must be devoted to the building structure and services than is required for lower buildings:

- More structure – because it must be stronger to support more floors above

- The elevator conundrum creates the need for more lift shafts—everyone comes in at the bottom and they all have to pass through the lower part of the building to get to the upper levels.

- Building services – power and water enter the building from below and have to pass through the lower levels to get to the upper levels.

story of the tallest skyscrapers

At the beginning of the 20th century, New York City was a center for the Beaux-Arts architectural movement, attracting the talents of such great architects as Stanford White and Carrere and Hastings. As better construction and engineering technology became available as the century progressed, New York City and Chicago became the focal point of the competition for the tallest building in the world. Each city's striking skyline has been composed of numerous and varied skyscrapers, many of which are icons of 20th-century architecture:

- The Flatiron Building, designed by Daniel Hudson Burnham and standing 285 ft (87 m) high, was one of the tallest buildings in New York City upon its completion in 1902, made possible by its steel skeleton. It was one of the first buildings designed with a steel framework, and to achieve this height with other construction methods of that time would have been very difficult. (The Tower Building, designed by Bradford Gilbert and built in 1889, is considered by some to be New York City's first skyscraper, and may have been the first building in New York City to use a skeletal steel frame,[63] while the Home Insurance Building in Chicago, which was built in 1884, is considered the world's first skyscraper due to its steel skeleton).[64] Subsequent buildings such as the Singer Building and the Metropolitan Life Tower were higher still.

- The Woolworth Building, a neo-Gothic "Cathedral of Commerce" overlooking City Hall, was designed by Cass Gilbert. At 792 feet (241 m), it became the world's tallest building upon its completion in 1913, an honor it retained until 1930, when it was overtaken by 40 Wall Street.

- That same year, the Chrysler Building took the lead as the tallest building in the world, scraping the sky at 1,046 feet (319 m).[65] Designed by William Van Alen, an Art Deco style masterpiece with an exterior crafted of brick,[66] the Chrysler Building continues to be a favorite of New Yorkers to this day.[67]

- The Empire State Building, the first building to have more than 100 floors (it has 102), was completed the following year. It was designed by Shreve, Lamb and Harmon in the contemporary Art Deco style. The tower takes its name from the nickname of New York State. Upon its completion in 1931 at 1,250 feet (381 m), it took the top spot as tallest building, and towered above all other buildings until 1972. The antenna mast added in 1951 brought pinnacle height to 1,472 feet (449 m), lowered in 1984 to 1,454 feet (443 m).[68]

- The World Trade Center officially reached full height in 1972, was completed in 1973, and consisted of two tall towers and several smaller buildings. For a short time, the first of the two towers was the world's tallest building. Upon completion, the towers stood for 28 years, until the September 11 attacks destroyed the buildings in 2001. Various governmental entities, financial firms, and law firms called the towers home.

- The Willis Tower (formerly Sears Tower) was completed in 1974, one year after the World Trade Center, and surpassed it as the world's tallest building. It was the first building to employ the "bundled tube" structural system, designed by Fazlur Khan. The building was not surpassed in height until the Petronas Towers were constructed in 1998, but remained the tallest in some categories until Burj Khalifa surpassed it in all categories in 2010. It is currently the second tallest building in the United States, after One World Trade Center, which was built to replace the destroyed towers.

This geographical transition is accompanied by a change in approach to skyscraper design. For much of the twentieth century large buildings took the form of simple geometrical shapes. This reflected the "international style" or modernist philosophy shaped by Bauhaus architects early in the century. The last of these, the Willis Tower and World Trade Center towers in New York, erected in the 1970s, reflect the philosophy. Tastes shifted in the decade which followed, and new skyscrapers began to exhibit postmodernist influences. This approach to design avails itself of historical elements, often adapted and re-interpreted, in creating technologically modern structures. The Petronas Twin Towers recall Asian pagoda architecture and Islamic geometric principles. Taipei 101 likewise reflects the pagoda tradition as it incorporates ancient motifs such as the ruyi symbol. The Burj Khalifa draws inspiration from traditional Islamic art. Architects in recent years have sought to create structures that would not appear equally at home if set in any part of the world, but that reflect the culture thriving in the spot where they stand.[citation needed]

The following list measures height of the roof.[69][not in citation given] The more common gauge is the "highest architectural detail"; such ranking would have included Petronas Towers, built in 1998.

| Built | Building | City | Country | Roof | Floors | Pinnacle | Current status | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1870 | Equitable Life Building | New York City | 043 m | 142 ft | 8 | Destroyed by fire in 1912 | |||

| 1889 | Auditorium Building | Chicago | 082 m | 269 ft | 17 | 106 m | 349 ft | Standing | |

| 1890 | New York World Building | New York City | 094 m | 309 ft | 20 | 106 m | 349 ft | Demolished in 1955 | |

| 1894 | Manhattan Life Insurance Building | 106 m | 348 ft | 18 | Demolished in 1963 | ||||

| 1895 | Milwaukee City Hall | Milwaukee | 108 m | 353 ft | 15 | Standing | |||

| 1899 | Park Row Building | New York City | 119 m | 391 ft | 30 | Standing | |||

| 1901 | Philadelphia City Hall | Philadelphia | 155.8 m | 511 ft | 9 | 167 m | 548 ft | Standing | |

| 1908 | Singer Building | New York City | 187 m | 612 ft | 47 | Demolished in 1968 | |||

| 1909 | Met Life Tower | 213 m | 700 ft | 50 | Standing | ||||

| 1913 | Woolworth Building | 241 m | 792 ft | 57 | Standing | ||||

| 1930 | 40 Wall Street | 70 | 283 m | 927 ft | Standing | ||||

| 1930 | Chrysler Building | 282.9 m | 927 ft | 77 | 319 m | 1,046 ft | Standing | ||

| 1931 | Empire State Building | 381 m | 1,250 ft | 102 | 443 m | 1,454 ft | Standing | ||

| 1972 | World Trade Center (North Tower) | 417 m | 1,368 ft | 110 | 527.3 m | 1,730 ft | Destroyed in 2001 in the September 11 attacks | ||

| 1974 | Willis Tower (formerly Sears Tower) | Chicago | 442 m | 1,450 ft | 108 | 527 m | 1,729 ft | Standing | |

| 1996 | Petronas Towers | Kuala Lumpur | 379 m | 1,242 ft | 88 | 452 m | 1,483 ft | Standing | |

| 2004 | Taipei 101 | Taipei | 449 m | 1,474 ft | 101 | 509 m | 1,671 ft | Standing | |

| 2010 | Burj Khalifa | Dubai | 828 m | 2,717 ft | 163 | 829.8 m | 2,722 ft | Standing | |

Photo gallery

|

Cancellation

Many skyscrapers were never built due to financial problems, politics and culture. The Chicago Spire was to be the tallest building in the Western Hemisphere, but it was on hold due to the global financial crisis of 2008. One year later, the project was cancelled.- The 610-metre (2,000 ft) Russia Tower was cancelled due to the global financial crisis of 2008. It would have dominated the Moscow skyline.

- Proposed in 1989, The Miglin-Beitler Skyneedle of Chicago would have been the tallest freestanding in the world. But it was never built due to the Persian gulf war.

- The cancelled Chicago World Trade Center would have been the first skyscraper to exceed a height of 700 metres (2,300 ft). It was proposed in the 1990s, a second one was to be completed but never built.

- The construction of the 200-floor, Dubai's Nakheel Tower—which was planned to be taller than 1,000 metres (3,300 ft)—was halted due to financial problems; 18 months later the project was cancelled.

- Harry Grant's Grant USA Tower in Newark, New Jersey was never built due to bankruptcy, the tower would have more than 550 meters tall.[70]

- Project 2000 Tower in Chicago was cancelled and never built, it would have had a height of 610 metres (2,000 ft)

- The proposed 1 New York Place would have had a height of 320 metres (1,050 ft), but was never built.

- Vision Brisbane was to be the tallest building in Brisbane and third tallest in Australia if built. It was cancelled due to the 2008 global financial crisis and the site was eventually sold where construction of a skyscraper of similar height was approved.

- The original design of Hong Kong's International Commerce Centre, with a height of 574 metres (1,883 ft), was supposed to have a crystal facade. It was changed and decreased to 484 metres (1,588 ft) due to height restrictions.

Future developments

At the time Taipei 101 broke the half-km mark in height, it was already technically possible to build structures towering over a km above the ground.[citation needed] Proposals for such structures have been put forward, including the Burj Mubarak Al Kabir in Kuwait and Azerbaijan Tower in Baku. Kilometer-plus structures present architectural challenges that may eventually place them in a new architectural category.[71] The first building under construction and planned to be over one kilometre tall is the Jeddah Tower.Wooden skyscrapers

Several wooden skyscraper designs have been designed and built, with the tallest currently being built is a 14-story housing project in Bergen, Norway known as 'Treet' or 'The Tree' to be finished November 2016.[72][73] Other buildings include Brock Commons an 18-story wooden dormitory at the University of British Columbia in Canada to be completed in 2017.[74] A 40-story residential building 'Trätoppen' has been proposed by architect Anders Berensson to be built in Stockholm, Sweden.[75]Wooden skyscrapers are estimated to be around a quarter of the weight of an equivalent reinforced-concrete structure as well as reducing the building carbon footprint by 60–75%. Buildings have been designed using cross-laminated timber (CLT) which gives a higher rigidity and strength to wooden structures. CLT panels are prefabricated and can therefore speed up building time.

X . II The elevator conundrum

Skyscraper design and construction

The design and construction of skyscrapers involves creating safe, habitable spaces in very high buildings. The buildings must support their weight, resist wind and earthquakes, and protect occupants from fire. Yet they must also be conveniently accessible, even on the upper floors, and provide utilities and a comfortable climate for the occupants. The problems posed in skyscraper design are considered among the most complex encountered given the balances required between economics, engineering, and construction management .

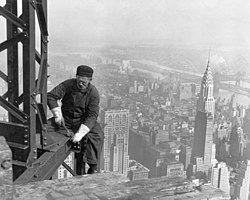

A workman on the framework of the Empire State Building

Basic design considerations

Good structural design is important in most building designs, but particularly for skyscrapers since even a small chance of catastrophic failure is unacceptable given the high prices of construction. This presents a paradox to civil engineers: the only way to assure a lack of failure is to test for all modes of failure, in both the laboratory and the real world. But the only way to know of all modes of failure is to learn from previous failures. Thus, no engineer can be absolutely sure that a given structure will resist all loadings that could cause failure, but can only have large enough margins of safety such that a failure is acceptably unlikely. When buildings do fail, engineers question whether the failure was due to some lack of foresight or due to some unknowable factor.Loading and vibration

The load a skyscraper experiences is largely from the force of the building material itself. In most building designs, the weight of the structure is much larger than the weight of the material that it will support beyond its own weight. In technical terms, the dead load, the load of the structure, is larger than the live load, the weight of things in the structure (people, furniture, vehicles, etc.). As such, the amount of structural material required within the lower levels of a skyscraper will be much larger than the material required within higher levels. This is not always visually apparent. The Empire State Building's setbacks are actually a result of the building code at the time, and were not structurally required. On the other hand, John Hancock Center's shape is uniquely the result of how it supports loads. Vertical supports can come in several types, among which the most common for skyscrapers can be categorized as steel frames, concrete cores, tube within tube design, and shear walls.The wind loading on a skyscraper should also be considered. In fact, the lateral wind load imposed on super-tall structures is generally the governing factor in the structural design. Wind pressure increases with height, so for very tall buildings, the loads associated with wind are larger than dead or live loads.

Other vertical and horizontal loading factors come from varied, unpredictable sources, such as earthquakes.

Shear walls

A shear wall, in its simplest definition, is a wall where the entire material of the wall is employed in the resistance of both horizontal and vertical loads. A typical example is a brick or cinderblock wall. Since the wall material is used to hold the weight, as the wall expands in size, it must hold considerably more weight. Due to the features of a shear wall, it is acceptable for small constructions, such as suburban housing or an urban brownstone, to require low material costs and little maintenance. In this way, shear walls, typically in the form of plywood and framing, brick, or cinderblock, are used for these structures. For skyscrapers, though, as the size of the structure increases, so does the size of the supporting wall. Large structures such as castles and cathedrals inherently addressed these issues due to a large wall being advantageous (castles), or able to be designed around (cathedrals). Since skyscrapers seek to maximize the floor-space by consolidating structural support, shear walls tend to be used only in conjunction with other support systems.Steel frame

The classic concept of a skyscraper is a large steel box with many small boxes inside it. By eliminating the inefficient part of a shear wall, the central portion, and consolidating support members in a much stronger material, steel, a skyscraper could be built with both horizontal and vertical supports throughout. This method, though simple, has drawbacks. Chief among these is that as more material must be supported (as height increases), the distance between supporting members must decrease, which actually, in turn, increases the amount of material that must be supported. This becomes inefficient and uneconomic for buildings above 40 stories tall as usable floor spaces are reduced for supporting column and due to more usage of steel.Tube frame

The Willis Tower showing the bundled tube frame design

A variation on the tube frame is the bundled tube, which uses several interconnected tube frames. The Willis Tower in Chicago used this design, employing nine tubes of varying height to achieve its distinct appearance. The bundle tube design was not only highly efficient in economic terms, but it was also "innovative in its potential for versatile formulation of architectural space. Efficient towers no longer had to be box-like; the tube-units could take on various shapes and could be bundled together in different sorts of groupings."[5] The bundled tube structure meant that "buildings no longer need be boxlike in appearance: they could become sculpture."[6] Cities have experienced a huge surge in skyscraper construction, thanks to Khan's innovations allowing economic skyscrapers.

The tubular systems are fundamental to tall building design. Most buildings over 40-stories constructed since the 1960s now use a tube design derived from Khan’s structural engineering principles,[1][7] examples including the construction of the World Trade Center, Aon Centre, Petronas Towers, Jin Mao Building, and most other supertall skyscrapers since the 1960s.[8] The strong influence of tube structure design is also evident in the construction of the current tallest skyscraper, the Burj Khalifa.[6]

The elevator conundrum

The invention of the elevator was a precondition for the invention of skyscrapers, given that most people would not (or could not) climb more than a few flights of stairs at a time. The elevators in a skyscraper are not simply a necessary utility like running water and electricity, but are in fact closely related to the design of the whole structure. A taller building requires more elevators to service the additional floors, but the elevator shafts consume valuable floor space. If the service core (which contains the elevator shafts) becomes too big, it can reduce the profitability of the building. Architects must therefore balance the value gained by adding height against the value lost to the expanding service core.[9] Many tall buildings use elevators in a non-standard configuration to reduce their footprint. Buildings such as the former World Trade Center Towers and Chicago's John Hancock Center use sky lobbies, where express elevators take passengers to upper floors which serve as the base for local elevators. This allows architects and engineers to place elevator shafts on top of each other, saving space. Sky lobbies and express elevators take up a significant amount of space and add to the amount of time spent commuting between floors. Other buildings such as the Petronas Towers use double-deck elevators allowing more people to fit in a single elevator and reaching two floors at every stop. It is possible to use even more than two levels on an elevator although this has yet to be tried. The main problem with double-deck elevators is that they cause everyone in the elevator to stop when only people on one level need to get off at a given floor.X . III Elevator

An elevator (US and Canada) or lift (UK, Australia,Ireland, New Zealand, and South Africa[8]) is a type of vertical transportation that moves people or goods between floors (levels, decks) of a building, vessel, or other structure. Elevators/lifts are generally powered by electric motors that either drive traction cables and counterweight systems like a hoist, or pump hydraulic fluid to raise a cylindrical piston like a jack.

In agriculture and manufacturing, an elevator/lift is any type of conveyor device used to lift materials in a continuous stream into bins or silos. Several types exist, such as the chain and bucket elevator, grain auger screw conveyor using the principle of Archimedes' screw, or the chain and paddles or forks of hay elevators.

Languages other than English may have loanwords based on either elevator or lift.

Because of wheelchair access laws, elevators/lifts are often a legal requirement in new multistory buildings, especially where wheelchair ramps would be impractical.

A set of lifts in the lower level of Borough station on the London Underground Northern line. The "up" and "down" arrows indicate each lift's position and direction of travel. Notice how the next lift is indicated with a right and left arrow by the words "Next Lift" at the top.

A set of lifts in the lower level of Borough station on the London Underground Northern line. The "up" and "down" arrows indicate each lift's position and direction of travel. Notice how the next lift is indicated with a right and left arrow by the words "Next Lift" at the top.

the top.

This elevator to the Alexanderplatz U-Bahn station in Berlin is built with glass walls, exposing the inner workings.

This elevator to the Alexanderplatz U-Bahn station in Berlin is built with glass walls, exposing the inner workings.

Glass elevator traveling up the facade of Westport Plaza. An HVAC unit is on top of the car because the elevator is completely outside.

Glass elevator traveling up the facade of Westport Plaza. An HVAC unit is on top of the car because the elevator is completely outside.

Freight elevator at North Carolina State University. The doors open vertically.

Freight elevator at North Carolina State University. The doors open vertically.

This elevator to the Alexanderplatz U-Bahn station in Berlin is built with glass walls, exposing the inner workings.

Glass elevator traveling up the facade of Westport Plaza. An HVAC unit is on top of the car because the elevator is completely outside.

Freight elevator at North Carolina State University. The doors open vertically.

Pre-industrial era

Elevator design by the German engineer Konrad Kyeser (1405)

The earliest known reference to an elevator is in the works of the Roman architect Vitruvius, who reported that Archimedes (c. 287 BC – c. 212 BC) built his first elevator probably in 236 BC.[9] Some sources from later historical periods mention elevators as cabs on a hemp rope powered by hand or by animals.

Elevator design by the German engineer Konrad Kyeser (1405)

The earliest known reference to an elevator is in the works of the Roman architect Vitruvius, who reported that Archimedes (c. 287 BC – c. 212 BC) built his first elevator probably in 236 BC.[9] Some sources from later historical periods mention elevators as cabs on a hemp rope powered by hand or by animals.

In 1000, the Book of Secrets by al-Muradi in Islamic Spain described the use of an elevator-like lifting device, in order to raise a large battering ram to destroy a fortress.[10] In the 17th century the prototypes of elevators were located in the palace buildings of England and France. Louis XV of France had a so-called 'flying chair' built for one of his mistresses at the Chateau de Versailles in 1743.[11]

Ancient and medieval elevators used drive systems based on hoists or winders. The invention of a system based on the screw drive was perhaps the most important step in elevator technology since ancient times, leading to the creation of modern passenger elevators. The first screw drive elevator was built by Ivan Kulibin and installed in Winter Palace in 1793. Several years later another of Kulibin's elevators was installed in Arkhangelskoye near Moscow.

Elevator design by the German engineer Konrad Kyeser (1405)

Industrial era

The development of elevators was led by the need for movement of raw materials including coal and lumber from hillsides. The technology developed by these industries and the introduction of steel beam construction worked together to provide the passenger and freight elevators in use today.

Starting in the coal mines, by the mid-19th century elevators were operated with steam power and were used for moving goods in bulk in mines and factories. These steam driven devices were soon being applied to a diverse set of purposes – in 1823, two architects working in London, Burton and Hormer, built and operated a novel tourist attraction, which they called the "ascending room". It elevated paying customers to a considerable height in the center of London, allowing them a magnificent panoramic view of downtown.[12]

Early, crude steam-driven elevators were refined in the ensuing decade; – in 1835 an innovative elevator called the "Teagle" was developed by the company Frost and Stutt in England. The elevator was belt-driven and used a counterweight for extra power.[13]

The hydraulic crane was invented by Sir William Armstrong in 1846, primarily for use at the Tyneside docks for loading cargo. These quickly supplanted the earlier steam driven elevators: exploiting Pascal's law, they provided a much greater force. A water pump supplied a variable level of water pressure to a plunger encased inside a vertical cylinder, allowing the level of the platform (carrying a heavy load) to be raised and lowered. Counterweights and balances were also used to increase the lifting power of the apparatus.

Henry Waterman of New York is credited with inventing the "standing rope control" for an elevator in 1850.[14]

In 1845, the Neapolitan architect Gaetano Genovese installed in the Royal Palace of Caserta the "Flying Chair", an elevator ahead of its time, covered with chestnut wood outside and with maple wood inside. It included a light, two benches and a hand operated signal, and could be activated from the outside, without any effort on the part of the occupants. Traction was controlled by a motor mechanic utilizing a system of toothed wheels. A safety system was designed to take effect if the cords broke. It consisted of a beam pushed outwards by a steel spring.

In 1852, Elisha Otis introduced the safety elevator, which prevented the fall of the cab if the cable broke. The design of the Otis safety elevator is somewhat similar to one type still used today. A governor device engages knurled roller(s), locking the elevator to its guides should the elevator descend at excessive speed. He demonstrated it at the New York exposition in the Crystal Palace in a dramatic, death-defying presentation in 1854,[14][15] and the first such passenger elevator was installed at 488 Broadway in New York City on March 23, 1857.

The first elevator shaft preceded the first elevator by four years. Construction for Peter Cooper's Cooper Union Foundation building in New York began in 1853. An elevator shaft was included in the design, because Cooper was confident that a safe passenger elevator would soon be invented.[16] The shaft was cylindrical because Cooper thought it was the most efficient design.[17] Later, Otis designed a special elevator for the building.

The Equitable Life Building completed in 1870 in New York City was thought to be the first office building to have passenger elevators.[18] However Peter Ellis and English architect installed the first elevators that could be described as paternoster lifts in Oriel Chambers in Liverpool in 1868.[19]

Schuyler Wheeler invented the electric elevator, patenting it in 1883.[20][21][22]

The first electric elevator was built by Werner von Siemens in 1880 in Germany.[23] The inventor Anton Freissler developed the ideas of von Siemens and built up a successful enterprise in Austria-Hungary. The safety and speed of electric elevators were significantly enhanced by Frank Sprague who added floor control, automatic elevators, acceleration control of cars, and safeties. His elevator ran faster and with larger loads than hydraulic or steam elevators, and 584 electric elevators were installed before Sprague sold his company to the Otis Elevator Company in 1895. Sprague also developed the idea and technology for multiple elevators in a single shaft.

In 1882, when hydraulic power was a well established technology, a company later named the London Hydraulic Power Company was formed by Edward B. Ellington and others. It constructed a network of high-pressure mains on both sides of the Thames which, ultimately, extended to 184 miles and powered some 8,000 machines, predominantly elevators (lifts) and cranes.[24]

In 1874, J.W. Meaker patented a method which permitted elevator doors to open and close safely.[25] In 1887, American Inventor Alexander Miles of Duluth, Minnesota patented an elevator with automatic doors that would close off the elevator shaft.

The first elevator in India was installed at the Raj Bhavan in Calcutta (now Kolkata) by Otis in 1892.[26]

By 1900, completely automated elevators were available, but passengers were reluctant to use them. A 1945 elevator operator strike in New York City, and adoption of an emergency stop button, emergency telephone, and a soothing explanatory automated voice aided adoption.[27]

In 2000, the first vacuum elevator was offered commercially in Argentina.[28]

Design

Some people argue that elevators began as simple rope or chain hoists (see Traction elevators below). An elevator is essentially a platform that is either pulled or pushed up by a mechanical means. A modern-day elevator consists of a cab (also called a "cage", "carriage" or "car") mounted on a platform within an enclosed space called a shaft or sometimes a "hoistway". In the past, elevator drive mechanisms were powered by steam and water hydraulic pistons or by hand. In a "traction" elevator, cars are pulled up by means of rolling steel ropes over a deeply grooved pulley, commonly called a sheave in the industry. The weight of the car is balanced by a counterweight. Sometimes two elevators are built so that their cars always move synchronously in opposite directions, and are each other's counterweight.

The friction between the ropes and the pulley furnishes the traction which gives this type of elevator its name.

Hydraulic elevators use the principles of hydraulics (in the sense of hydraulic power) to pressurize an above ground or in-ground piston to raise and lower the car (see Hydraulic elevators below). Roped hydraulics use a combination of both ropes and hydraulic power to raise and lower cars. Recent innovations include permanent magnet motors, machine room-less rail mounted gearless machines, and microprocessor controls.

The technology used in new installations depends on a variety of factors. Hydraulic elevators are cheaper, but installing cylinders greater than a certain length becomes impractical for very-high lift hoistways. For buildings of much over seven floors, traction elevators must be employed instead. Hydraulic elevators are usually slower than traction elevators.

Elevators are a candidate for mass customization. There are economies to be made from mass production of the components, but each building comes with its own requirements like different number of floors, dimensions of the well and usage patterns.

Elevator doors

Elevator doors protect riders from falling into the shaft. The most common configuration is to have two panels that meet in the middle, and slide open laterally. In a cascading telescopic configuration (potentially allowing wider entryways within limited space), the doors roll on independent tracks so that while open, they are tucked behind one another, and while closed, they form cascading layers on one side. This can be configured so that two sets of such cascading doors operate like the center opening doors described above, allowing for a very wide elevator cab. In less expensive installations the elevator can also use one large "slab" door: a single panel door the width of the doorway that opens to the left or right laterally. Some buildings have elevators with the single door on the shaft way, and double cascading doors on the cab.

Machine room-less (MRL) elevators

Machine room-less elevators are designed so that most of the components fit within the shaft containing the elevator car; and a small cabinet houses the elevator controller. Other than the machinery being in the hoistway, the equipment is similar to a normal traction or hole-less hydraulic elevator. The world's first machine room-less elevator, the Kone MonoSpace was introduced in 1996, by Kone. The benefits are:

- creates more usable space

- use less energy (70–80% less than standard hydraulic elevators)

- uses no oil (assuming it is a traction elevator)

- all components are above ground similar to roped hydraulic type elevators (this takes away the environmental concern that was created by the hydraulic cylinder on direct hydraulic type elevators being stored underground)

- slightly lower cost than other elevators; significantly so for the hydraulic MRL elevator

- can operate at faster speeds than hydraulics but not normal traction units.

Detriments

- Equipment can be harder to service and maintain.

- No code has been approved for the installation of residential elevator equipment.

- Code is not universal for hydraulic machine room less elevators.

Facts

- Noise level is at 50–55 dBA (A-weighted decibels), which can be lower than some but not all types of elevators.

- Usually used for low-rise to mid-rise buildings

- The motor mechanism is placed in the hoistway itself

- The US was slow to accept the commercial MRL Elevator because of codes

- National and local building codes did not address elevators without machine rooms. Residential MRL Elevators are still not allowed by the ASME A17 code in the US. MRL elevators have been recognized in the 2005 supplement to the 2004 A17.1 Elevator Code.

- Today, some machine room less hydraulic elevators by Otis and ThyssenKrupp exist; they do not involve the use of a piston located underground or a machine room, mitigating environmental concerns; however, code is not yet accepting of them in all parts of the United States.

Elevator traffic calculations

Round-trip time calculations

The majority of elevator designs are developed from Up Peak Round Trip Time calculations as described in the following publications:- CIBSE Guide D: Transportation Systems in Building[31] Elevator Traffic Handbook, Theory and Practice. Gina Barney.[32] The Vertical Transportation Handbook. George Strakosch[33]

Traditionally, these calculations have formed the basis of establishing the Handling Capacity of an elevator system.

Modern Installations with more complex elevator arrangements have led to the development of more specific formula such as the General Analysis calculation.[34]

Subsequently, this has been extended for Double Deck elevators.[35]

Otis Elevator Company operates more than 1.9 million elevators worldwide, giving rise to its claim that the equivalent of the world population is transported by its products every five days.[citation needed]

Simulation

Elevator traffic simulation software can be used to model complex traffic patterns and elevator arrangements that cannot necessarily be analyzed by RTT calculations.[36]

Elevator traffic patterns

There are four main types of elevator traffic patterns that can be observed in most modern office installations. They are up peak traffic, down peak traffic, lunch time (two way) traffic and interfloor traffic.

Types of hoist mechanisms

Elevators can be rope dependent or rope-free.[37] There are at least four means of moving an elevator:

Traction elevators

- Geared and gearless traction elevators

Geared traction machines are driven by AC or DC electric motors. Geared machines use worm gears to control mechanical movement of elevator cars by "rolling" steel hoist ropes over a drive sheave which is attached to a gearbox driven by a high-speed motor. These machines are generally the best option for basement or overhead traction use for speeds up to 3 m/s (500 ft/min).[38]

Historically, AC motors were used for single or double speed elevator machines on the grounds of cost and lower usage applications where car speed and passenger comfort were less of an issue, but for higher speed, larger capacity elevators, the need for infinitely variable speed control over the traction machine becomes an issue. Therefore, DC machines powered by an AC/DC motor generator were the preferred solution. The MG set also typically powered the relay controller of the elevator, which has the added advantage of electrically isolating the elevators from the rest of a building's electrical system, thus eliminating the transient power spikes in the building's electrical supply caused by the motors starting and stopping (causing lighting to dim every time the elevators are used for example), as well as interference to other electrical equipment caused by the arcing of the relay contactors in the control system.

The widespread availability of variable frequency AC drives has allowed AC motors to be used universally, bringing with it the advantages of the older motor-generator, DC-based systems, without the penalties in terms of efficiency and complexity. The older MG-based installations are gradually being replaced in older buildings due to their poor energy efficiency.

Gearless traction machines are low-speed (low-RPM), high-torque electric motors powered either by AC or DC. In this case, the drive sheave is directly attached to the end of the motor. Gearless traction elevators can reach speeds of up to 20 m/s (4,000 ft/min), A brake is mounted between the motor and gearbox or between the motor and drive sheave or at the end of the drive sheave to hold the elevator stationary at a floor. This brake is usually an external drum type and is actuated by spring force and held open electrically; a power failure will cause the brake to engage and prevent the elevator from falling (see inherent safety and safety engineering). But it can also be some form of disc type like 1 or more calipers over a disc in one end of the motor shaft or drive sheave which is used in high speed, high rise and large capacity elevators with machine rooms(an exception is the Kone MonoSpace's EcoDisc which is not high speed, high rise and large capacity and is machine room less but it uses the same design as is a thinner version of a conventional gearless traction machine) for braking power, compactness and redundancy (assuming there's at least 2 calipers on the disc), or 1 or more disc brakes with a single caliper at one end of the motor shaft or drive sheave which is used in machine room less elevators for compactness, braking power, and redundancy (assuming there's 2 brakes or more).

In each case, cables are attached to a hitch plate on top of the cab or may be "underslung" below a cab, and then looped over the drive sheave to a counterweight attached to the opposite end of the cables which reduces the amount of power needed to move the cab. The counterweight is located in the hoist-way and rides a separate railway system; as the car goes up, the counterweight goes down, and vice versa. This action is powered by the traction machine which is directed by the controller, typically a relay logic or computerized device that directs starting, acceleration, deceleration and stopping of the elevator cab. The weight of the counterweight is typically equal to the weight of the elevator cab plus 40–50% of the capacity of the elevator. The grooves in the drive sheave are specially designed to prevent the cables from slipping. "Traction" is provided to the ropes by the grip of the grooves in the sheave, thereby the name. As the ropes age and the traction grooves wear, some traction is lost and the ropes must be replaced and the sheave repaired or replaced. Sheave and rope wear may be significantly reduced by ensuring that all ropes have equal tension, thus sharing the load evenly. Rope tension equalization may be achieved using a rope tension gauge, and is a simple way to extend the lifetime of the sheaves and ropes.

Elevators with more than 30 m (98 ft) of travel have a system called compensation. This is a separate set of cables or a chain attached to the bottom of the counterweight and the bottom of the elevator cab. This makes it easier to control the elevator, as it compensates for the differing weight of cable between the hoist and the cab. If the elevator cab is at the top of the hoist-way, there is a short length of hoist cable above the car and a long length of compensating cable below the car and vice versa for the counterweight. If the compensation system uses cables, there will be an additional sheave in the pit below the elevator, to guide the cables. If the compensation system uses chains, the chain is guided by a bar mounted between the counterweight railway lines.

Hydraulic elevators

- Conventional hydraulic elevators. They use an underground hydraulic cylinder, are quite common for low level buildings with two to five floors (sometimes but seldom up to six to eight floors), and have speeds of up to 1 m/s (200 ft/min). For higher rise applications, a telescopic hydraulic cylinder can be used.[citation needed]

- Holeless hydraulic elevators were developed in the 1970s, and use a pair of above ground cylinders, which makes it practical for environmentally or cost sensitive buildings with two, three, or four floors.

- Roped hydraulic elevators use both above ground cylinders and a rope system, allowing the elevator to travel further than the piston has to move.

The low mechanical complexity of hydraulic elevators in comparison to traction elevators makes them ideal for low rise, low traffic installations. They are less energy efficient as the pump works against gravity to push the car and its passengers upwards; this energy is lost when the car descends on its own weight. The high current draw of the pump when starting up also places higher demands on a building’s electrical system. There are also environmental concerns should the lifting cylinder leak fluid into the ground.[39]

The modern generation of low cost, machine room-less traction elevators made possible by advances in miniaturization of the traction motor and control systems challenges the supremacy of the hydraulic elevator in their traditional market niche.

Climbing elevator

A climbing elevator is a self-ascending elevator with its own propulsion. The propulsion can be done by an electric or a combustion engine. Climbing elevators are used in guyed masts or towers, in order to make easy access to parts of these constructions, such as flight safety lamps for maintenance. An example would be the Moonlight towers in Austin, Texas, where the elevator holds only one person and equipment for maintenance. The Glasgow Tower — an observation tower in Glasgow, Scotland — also makes use of two climbing elevators. The ThyssenKrupp MULTI elevator system is based on this principle and it uses a linear motor, like the ones used in maglev trains, to move an elevator car both horizontally and vertically.[40]

Pneumatic elevator

An elevator of this kind uses a vacuum on top of the cab and a valve on the top of the "shaft" to move the cab upwards and closes the valve in order to keep the cab at the same level. A diaphragm or a piston is used as a "brake", if there's a sudden increase in pressure above the cab. To go down, it opens the valve so that the air can pressurize the top of the "shaft", allowing the cab to go down by its own weight. This also means that in case of a power failure, the cab will automatically go down. The "shaft" is made of acylic, and is always round due to the shape of the vacuum pump turbine. In order to keep the air inside of the cab, rubber seals are used. Due to technical limitations, these elevators have a low capacity, they usually allow 1–3 passengers and up to 525 lbs.

Controlling elevators

Manual controls

In the first half of the twentieth century, almost all elevators had no automatic positioning of the floor on which the cab would stop. Some of the older freight elevators were controlled by switches operated by pulling on adjacent ropes. In general, most elevators before WWII were manually controlled by elevator operators using a rheostat connected to the motor. This rheostat (see picture) was enclosed within a cylindrical container about the size and shape of a cake. This was mounted upright or sideways on the cab wall and operated via a projecting handle, which was able to slide around the top half of the cylinder.

The elevator motor was located at the top of the shaft or beside the bottom of the shaft. Pushing the handle forward would cause the cab to rise; backwards would make it sink. The harder the pressure, the faster the elevator would move. The handle also served as a dead man switch: if the operator let go of the handle, it would return to its upright position, causing the elevator cab to stop. In time, safety interlocks would ensure that the inner and outer doors were closed before the elevator was allowed to move.

This lever would allow some control over the energy supplied to the motor and so enabled the elevator to be accurately positioned — if the operator was sufficiently skilled. More typically, the operator would have to "jog" the control, moving the cab in small increments until the elevator was reasonably close to the landing point. Then the operator would direct the outgoing and incoming passengers to "watch the step".

Automatic elevators began to appear as early as the 1930s, their development being hastened by striking elevator operators which brought large cities dependent on skyscrapers (and therefore their elevators) such as New York and Chicago to their knees. These electromechanical systems used relay logic circuits of increasing complexity to control the speed, position and door operation of an elevator or bank of elevators.

The Otis Autotronic system of the early 1950s brought the earliest predictive systems which could anticipate traffic patterns within a building to deploy elevator movement in the most efficient manner. Relay-controlled elevator systems remained common until the 1980s and their gradual replacement with solid-state, microprocessor-based controls are now the industry standard. Most older, manually-operated elevators have been retrofitted with automatic or semi-automatic controls.

Using the emergency call button in an elevator. There is Braille text for visually impaired people and the button glows to alert a hearing impaired person that the bell is ringing and the call is being placed.

Using the emergency call button in an elevator. There is Braille text for visually impaired people and the button glows to alert a hearing impaired person that the bell is ringing and the call is being placed.

Using the emergency call button in an elevator. There is Braille text for visually impaired people and the button glows to alert a hearing impaired person that the bell is ringing and the call is being placed.

General controls

A typical modern passenger elevator will have:

- Space to stand in, guardrails, seating cushion (luxury)

- Overload sensor — prevents the elevator from moving until excess load has been removed. It may trigger a voice prompt or buzzer alarm. This may also trigger a "full car" indicator, indicating the car's inability to accept more passengers until some are unloaded.

- Electric fans or air conditioning units to enhance circulation and comfort.

- A control panel with various buttons. In the United States and other countries, button text and icons are raised to allow blind users to operate the elevator; many have Braille text besides. Buttons include:

- Call buttons to choose a floor. Some of these may be key switches (to control access). In some elevators, certain floors are inaccessible unless one swipes a security card or enters a passcode (or both).

- Door open and Door close buttons.

The operation of the door open button is transparent, immediately opening and holding the door, typically until a timeout occurs and the door closes. The operation of the door close button is less transparent, and it often appears to do nothing, leading to frequent but incorrect[41] reports that the door close button is a placebo button: either not wired up at all, or inactive in normal service.Working door open and door close buttons are required by code in many jurisdictions, including the United States, specifically for emergency operation: in independent mode, the door open and door close buttons are used to manually open or close the door.[41][46] Beyond this, programming varies significantly, with some door close buttons immediately closing the door, but in other cases being delayed by an overall timeout, so the door cannot be closed until a few seconds after opening. In this case (hastening normal closure), the door close button has no effect. However, the door close button will cause a hall call to be ignored (so the door won't reopen), and once the timeout has expired, the door close will immediately close the door, for example to cancel a door open push. The minimum timeout for automatic door closing in the US is 5 seconds,[47] which is a noticeable delay if not overridden.

- An alarm button or switch, which passengers can use to warn the premises manager that they have been trapped in the elevator.

- A set of doors kept locked on each floor to prevent unintentional access into the elevator shaft by the unsuspecting individual. The door is unlocked and opened by a machine sitting on the roof of the car, which also drives the doors that travel with the car. Door controls are provided to close immediately or reopen the doors, although the button to close them immediately is often disabled during normal operations, especially on more recent elevators. Objects in the path of the moving doors will either be detected by sensors or physically activate a switch that reopens the doors. Otherwise, the doors will close after a preset time. Some elevators are configured to remain open at the floor until they are required to move again.

- Elevators in high traffic buildings often have a "nudge" function (the Otis Autotronic system first introduced this feature) which will close the doors at a reduced speed, and sound a buzzer if the "door open" button is being deliberately held down, or if the door sensors have been blocked for too long a time.

- A stop switch (not allowed under British regulations) to halt the elevator while in motion and often used to hold an elevator open while freight is loaded. Keeping an elevator stopped for too long may set off an alarm. Unless local codes require otherwise, this will most likely be a key switch.

Some elevators may have one or more of the following:

- An elevator telephone, which can be used (in addition to the alarm) by a trapped passenger to call for help. This may consist of a transceiver, or simply a button.

- Hold button: This button delays the door closing timer, useful for loading freight and hospital beds.

- Call cancellation: A destination floor may be deselected by double clicking.

- Access restriction by key switches, RFID reader, code keypad, hotel room card, etc.