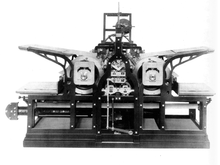

The first inventor of Print Media was Johannes Gutenberg and Paul fire in 1455 primarily in European countries. Initial development seen from the use of leaves or clay as a medium, form of media to printing. Gutenberg began printing the Bible through the printing technology he had invented. Gutenberg printing technology . technology also encourages increased production of the book into a count that is not small. Printing technology itself creates the momentum that actually makes this technology increasingly push itself to grow further.

Continued from the early development of print media is where the development of technology that has not developed, namely print media made using typewriters to create a product ad where the images or animations that make up the product ads are made manually by using a pen.

The signs of the development of print media are literacy (the ability to read and write). Indeed literacy is a condition that belongs to the elite. Developing languages are only a few basic languages, Latin - for example. The development of education in the 14th century also encouraged the development of literate people. The development of print media now is supported the development of technology that has developed, so it can facilitate people to create a more creative and attractive advertising.

The current development of print media is supported by increasingly sophisticated technological developments. Thus bringing changes to the form, format, structure, texture and model of the advertisement, but technological developments do not affect or alter the content of an advertisement that appears in the media. Making print media now with sophisticated technology is to use a computer to design advertisements of a product using graphics and printed with printers.

The development of print media technology related to the development of print media itself such as the emergence of magazines, newspapers, newspapers whose contents about articles on the theme of politics, art, culture, literature, public opinion and information about health can color the life of the community. For example in the article with the theme of politics, that the politics that increasingly entertain in the State. Then important events that affect the history of community life. Newspapers or commonly called newspapers is one of the print media of journalism in which the contents of articles containing about the information or news about human life, ranging from the theme of health, and work to advertising.

As for the magazine that was published first, and still remain the same contents with the magazine now, it is consistent with the print media. Usually from article articles contained in the print media.

Entering the period of 1960s, print media experienced major changes in the production process. The typewriter that used to be widely used for writing, began to be replaced by a computer. This is of course accompanied by various considerations and one of them more economical and efficient. Through computers, print media not only produces writing that can be changed without wasting paper but also can change a picture or photo. The work in the form of softcopy, then printed. In addition to the influence of the use of computers, photocopy technology also contributes where we can copy a paper with high speed and no minimum order so that we can copy as needed.

Another development of this technology is innovation over custom publishing where the publication of a writing or a book with a specific purpose and the end result is not intended to be marketed widely but turned into production for the purpose of order from consumers. When a book is printed, there must be a book production series code. Through electronic scanners, the code is recognized and sales data directly sent to the central database to see how much the sales of books directly, commonly known as electronic data processing.

Rolls of newsprint

Digital printing

By 2005, Digital printing accounts for approximately 9% of the 45 trillion pages printed annually around the world.Printing at home, an office, or an engineering environment is subdivided into:

- small format (up to ledger size paper sheets), as used in business offices and libraries

- wide format (up to 3' or 914mm wide rolls of paper), as used in drafting and design establishments.

- blueprint – and related chemical technologies

- daisy wheel – where pre-formed characters are applied individually

- dot-matrix – which produces arbitrary patterns of dots with an array of printing studs

- line printing – where formed characters are applied to the paper by lines

- heat transfer – such as early fax machines or modern receipt printers that apply heat to special paper, which turns black to form the printed image

- inkjet – including bubble-jet, where ink is sprayed onto the paper to create the desired image

- electrophotography – where toner is attracted to a charged image and then developed

- laser – a type of xerography where the charged image is written pixel by pixel using a laser

- solid ink printer – where cubes of ink are melted to make ink or liquid toner

Professional digital printing (using toner) primarily uses an electrical charge to transfer toner or liquid ink to the substrate onto which it is printed. Digital print quality has steadily improved from early color and black and white copiers to sophisticated colour digital presses such as the Xerox iGen3, the Kodak Nexpress, the HP Indigo Digital Press series, and the InfoPrint 5000. The iGen3 and Nexpress use toner particles and the Indigo uses liquid ink. The InfoPrint 5000 is a full-color, continuous forms inkjet drop-on-demand printing system. All handle variable data, and rival offset in quality. Digital offset presses are also called direct imaging presses, although these presses can receive computer files and automatically turn them into print-ready plates, they cannot insert variable data.

Small press and fanzines generally use digital printing. Prior to the introduction of cheap photocopying the use of machines such as the spirit duplicator, hectograph, and mimeograph was common.

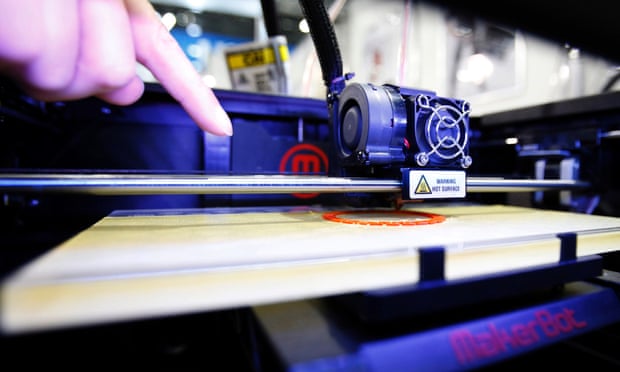

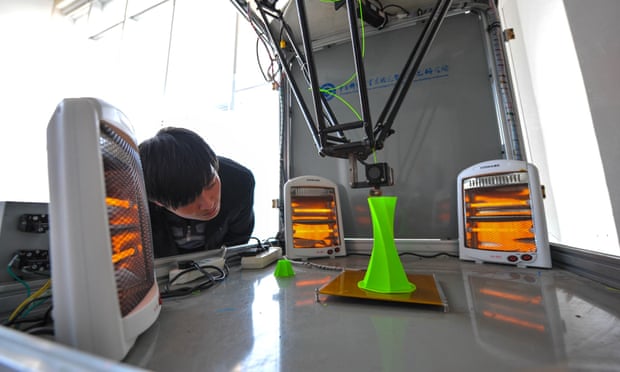

3D printing

3D printing is a form of manufacturing technology where physical objects are created from three-dimensional digital models using 3D printers. The objects are created by laying down or building up many thin layers of material in succession. The technique is also known as additive manufacturing, rapid prototyping, or fabricating.Gang run printing

Gang run printing is a method in which multiple printing projects are placed on a common paper sheet in an effort to reduce printing costs and paper waste. Gang runs are generally used with sheet-fed printing presses and CMYK process color jobs, which require four separate plates that are hung on the plate cylinder of the press. Printers use the term "gang run" or "gang" to describe the practice of placing many print projects on the same oversized sheet. Basically, instead of running one postcard that is 4 x 6 as an individual job the printer would place 15 different postcards on 20 x 18 sheet therefore using the same amount of press time the printer will get 15 jobs done in the roughly the same amount of time as one job.Printed electronics

Printed electronics is the manufacturing of electronic devices using standard printing processes. Printed electronics technology can be produced on cheap materials such as paper or flexible film, which makes it an extremely cost-effective method of production. Since early 2010, the printable electronics industry has been gaining momentum and several large companies, including Bemis Company and Illinois Tool Works have made investments in printed electronics and industry associations including OE-A and FlexTech Alliance are contributing heavily to the advancement of the printed electronics industry

Replica of the Gutenberg and Paula press at the International Printing Museum

The Printing Revolution

The Printing Revolution occurred when the spread of the printing press facilitated the wide circulation of information and ideas, acting as an "agent of change" through the societies that it reached.Mass production and spread of printed books

Spread of printing in the 15th century from Mainz, Germany

In Italy, a center of early printing, print shops had been established in 77 cities and towns by 1500. At the end of the following century, 151 locations in Italy had seen at one time printing activities, with a total of nearly three thousand printers known to be active. Despite this proliferation, printing centres soon emerged; thus, one third of the Italian printers published in Venice.

By 1500, the printing presses in operation throughout Western Europe had already produced more than twenty million copies. In the following century, their output rose tenfold to an estimated 150 to 200 million copies.

European printing presses of around 1600 were capable of producing about 1,500 impressions per workday. By comparison, book printing in East Asia, did not use presses and was solely done by block printing.

Of Erasmus's work, at least 750,000 copies were sold during his lifetime alone (1469–1536). In the early days of the Reformation, the revolutionary potential of bulk printing took princes and papacy alike by surprise. In the period from 1518 to 1524, the publication of books in Germany alone skyrocketed sevenfold; between 1518 and 1520, Luther's tracts were distributed in 300,000 printed copies.

The rapidity of typographical text production, as well as the sharp fall in unit costs, led to the issuing of the first newspapers (see Relation) which opened up an entirely new field for conveying up-to-date information to the public.

Incunable are surviving pre-16th century print works which are collected by many of the libraries in Europe and North America.

Circulation of information and ideas

"Modern Book Printing" sculpture, commemorating Gutenberg's invention on the occasion of the 2006 World Cup in Germany

Because the printing process ensured that the same information fell on the same pages, page numbering, tables of contents, and indices became common, though they previously had not been unknown. The process of reading also changed, gradually moving over several centuries from oral readings to silent, private reading. Over the next 200 years, the wider availability of printed materials led to a dramatic rise in the adult literacy rate throughout Europe.

The printing press was an important step towards the democratization of knowledge. Within 50 or 60 years of the invention of the printing press, the entire classical canon had been reprinted and widely promulgated throughout Europe (Eisenstein, 1969; 52). Now that more people had access to knowledge both new and old, more people could discuss these works. Furthermore, now that book production was a more commercial enterprise, the first copyright laws were passed to protect what we now would call intellectual property rights. On the other hand, the printing press was criticized for allowing the dissemination of information which may have been incorrect.

A second outgrowth of this popularization of knowledge was the decline of Latin as the language of most published works, to be replaced by the vernacular language of each area, increasing the variety of published works. The printed word also helped to unify and standardize the spelling and syntax of these vernaculars, in effect 'decreasing' their variability. This rise in importance of national languages as opposed to pan-European Latin is cited as one of the causes of the rise of nationalism in Europe.

Book printing as art form

For years, book printing was considered a true art form. Typesetting, or the placement of the characters on the page, including the use of ligatures, was passed down from master to apprentice. In Germany, the art of typesetting was termed the "black art", in allusion to the ink-covered printers. It has largely been replaced by computer typesetting programs, which make it easy to get similar results more quickly and with less physical labor. Some practitioners continue to print books the way Gutenberg did. For example, there is a yearly convention of traditional book printers in Mainz, Germany.Some theorists, such as McLuhan, Eisenstein, Kittler, and Giesecke, see an "alphabetic monopoly" as having developed from printing, removing the role of the image from society. Other authors stress that printed works themselves are a visual medium. Certainly, modern developments in printing have revitalized the role of illustrations.

Industrial printing presses

At the dawn of the Industrial Revolution, the mechanics of the hand-operated Gutenberg-style press were still essentially unchanged, although new materials in its construction, amongst other innovations, had gradually improved its printing efficiency. By 1800, Lord Stanhope had built a press completely from cast iron which reduced the force required by 90%, while doubling the size of the printed area. With a capacity of 480 pages per hour, it doubled the output of the old style press.Nonetheless, the limitations inherent to the traditional method of printing became obvious.

Koenig's 1814 steam-powered printing press

Koenig and Bauer sold two of their first models to The Times in London in 1814, capable of 1,100 impressions per hour. The first edition so printed was on 28 November 1814. They went on to perfect the early model so that it could print on both sides of a sheet at once. This began the long process of making newspapers available to a mass audience (which in turn helped spread literacy), and from the 1820s changed the nature of book production, forcing a greater standardization in titles and other metadata. Their company Koenig & Bauer AG is still one of the world's largest manufacturers of printing presses today.

The steam powered rotary printing press, invented in 1843 in the United States by Richard M. Hoe, allowed millions of copies of a page in a single day. Mass production of printed works flourished after the transition to rolled paper, as continuous feed allowed the presses to run at a much faster pace.

Also, in the middle of the 19th century, there was a separate development of jobbing presses, small presses capable of printing small-format pieces such as billheads, letterheads, business cards, and envelopes. Jobbing presses were capable of quick set-up (average setup time for a small job was under 15 minutes) and quick production (even on treadle-powered jobbing presses it was considered normal to get 1,000 impressions per hour [iph] with one pressman, with speeds of 1,500 iph often attained on simple envelope work). Job printing emerged as a reasonably cost-effective duplicating solution for commerce at this time.

By the late 1930s or early 1940s, printing presses had increased substantially in efficiency: a model by Platen Printing Press was capable of performing 2,500 to 3,000 impressions per hour.

Gallery

- Stanhope press from 1842

X . IIII

E-book

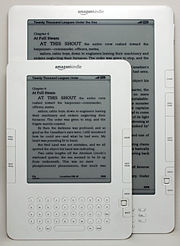

An electronic book (or e-book) is a book publication made available in digital form, consisting of text, images, or both, readable on the flat-panel display of computers or other electronic devices.Although sometimes defined as "an electronic version of a printed book", some e-books exist without a printed equivalent. Commercially produced and sold e-books are usually intended to be read on dedicated e-reader devices. However, almost any sophisticated computer device that features a controllable viewing screen can also be used to read e-books, including desktop computers, laptops, tablets and smartphones.

In the 2000s, there was a trend of print and e-book sales moving to the Internet, where readers buy traditional paper books and e-books on websites using e-commerce systems. With print books, readers are increasingly browsing through images of the covers of books on publisher or bookstore websites and selecting and ordering titles online; the paper books are then delivered to the reader by mail or another delivery service. With e-books, users can browse through titles online, and then when they select and order titles, the e-book can be sent to them online or the user can download the e-book. At the start of 2012 in the U.S., more e-books were published online than were distributed in hardcover.

The main reasons that people are buying e-books online are due to possibly lower prices, increased comfort (as they can buy from home or on the go with mobile devices) and a larger selection of titles. With e-books, "[e]lectronic bookmarks make referencing easier, and e-book readers may allow the user to annotate pages." "Although fiction and non-fiction books come in e-book formats, technical material is especially suited for e-book delivery because it can be [electronically] searched" for keywords. In addition, for programming books, code examples can be copied. E-book reading is increasing in the U.S.; by 2014, 28% of adults had read an e-book, compared to 23% in 2013. This is increasing, because by 2014 50% of American adults had an e-reader or a tablet, compared to 30% owning such devices in 2013.

Terminology

A woman reading an e-book on an e-reader.

The Readies (1930)

The idea of an e-reader that would enable a reader to view books on a screen came to Bob Brown after watching his first "talkie" (movie with sound). In 1930, he wrote a book on this idea and titled it The Readies, playing off the idea of the "talkie". In his book, Brown says movies have outmaneuvered the book by creating the "talkies" and, as a result, reading should find a new medium: "A machine that will allow us to keep up with the vast volume of print available today and be optically pleasing". Although Brown came up with the idea intellectually in the 1930s, early commercial e-readers did not follow his model. Nevertheless, Brown in many ways predicted what e-readers would become and what they would mean to the medium of reading. In an article, Jennifer Schuessler writes, "The machine, Brown argued, would allow readers to adjust the type size, avoid paper cuts and save trees, all while hastening the day when words could be ‘recorded directly on the palpitating ether.’" He felt the e-reader should bring a completely new life to the medium of reading. Schuessler relates it to a DJ spinning bits of old songs to create a beat or an entirely new song as opposed to just a remix of a familiar song.First inventor

The inventor of the first e-book is not widely agreed upon. Some notable candidates include the following:Ángela Ruiz Robles (1949)

In 1949, Ángela Ruiz Robles, a teacher from Galicia, Spain, patented in her country the first electronic book reader, the Enciclopedia Mecánica, or the Mechanical Encyclopedia. Her idea behind the device was to decrease the number of books that her pupils carried to school.Roberto Busa (late 1949–1970)

The first e-book may be the Index Thomisticus, a heavily annotated electronic index to the works of Thomas Aquinas, prepared by Roberto Busa beginning in 1949 and completed in the 1970s. Although originally stored on a single computer, a distributable CD-ROM version appeared in 1989. However, this work is sometimes omitted; perhaps because the digitized text was a means for studying written texts and developing linguistic concordances, rather than as a published edition in its own right. In 2005, the Index was published online.Doug Engelbart and Andries van Dam (1960s)

Alternatively, some historians consider electronic books to have started in the early 1960s, with the NLS project headed by Doug Engelbart at Stanford Research Institute (SRI), and the Hypertext Editing System and FRESS projects headed by Andries van Dam at Brown University.[14][15][16] Augment ran on specialized hardware, while FRESS ran on IBM mainframes. FRESS documents were structure-oriented rather than line-oriented, and were formatted dynamically for different users, display hardware, window sizes, and so on, as well as having automated tables of contents, indexes, and so on. All these systems also provided extensive hyperlinking, graphics, and other capabilities. Van Dam is generally thought to have coined the term "electronic book", and it was established enough to use in an article title by 1985.FRESS was used for reading extensive primary texts online, as well as for annotation and online discussions in several courses, including English Poetry and Biochemistry. Brown's faculty made extensive use of FRESS; for example the philosopher Roderick Chisholm used it to produce several of his books. Thus in the Preface to Person and Object (1979) he writes "The book would not have been completed without the epoch-making File Retrieval and Editing System..." Brown University's work in electronic book systems continued for many years, including US Navy funded projects for electronic repair-manuals; a large-scale distributed hypermedia system known as InterMedia; a spinoff company Electronic Book Technologies that built DynaText, the first SGML-based e-reader system; and the Scholarly Technology Group's extensive work on the Open eBook standard.

Michael S. Hart (1971)

Despite the extensive earlier history, several publications report Michael S. Hart as the inventor of the e-book. In 1971, the operators of the Xerox Sigma V mainframe at the University of Illinois gave Hart extensive computer-time. Seeking a worthy use of this resource, he created his first electronic document by typing the United States Declaration of Independence into a computer in plain text. Hart planned to create documents using plain text to make them as easy as possible to download and view on devices.Early implementations

After Hart first adapted the Declaration of Independence into an electronic document in 1971, Project Gutenberg was launched to create electronic copies of more texts - especially books.Another early e-book implementation was the desktop prototype for a proposed notebook computer, the Dynabook, in the 1970s at PARC: a general-purpose portable personal computer capable of displaying books for reading. In 1980 the US Department of Defense began concept development for a portable electronic delivery device for technical maintenance information called project PEAM, the Portable Electronic Aid for Maintenance. Detailed specifications were completed in FY 82, and prototype development began with Texas Instruments that same year. Four prototypes were produced and delivered for testing in 1986. Tests were completed in 1987. The final summary report was produced by the US Army research Institute for the Behavioral and Social Sciences in 1989 authored by Robert Wisher and J. Peter Kincaid. A patent application for the PEAM device was submitted by Texas Instruments titled "Apparatus for delivering procedural type instructions" was submitted Dec 4, 1985 listing John K. Harkins and Stephen H. Morriss as inventors.E-book formats

As e-book formats emerged and proliferated, some garnered support from major software companies, such as Adobe with its PDF format that was introduced in 1993. Different e-readers followed different formats, most of them specializing in only one format, thereby fragmenting the e-book market even more. Due to the exclusiveness and limited readerships of e-books, the fractured market of independent publishers and specialty authors lacked consensus regarding a standard for packaging and selling e-books. However, in the late 1990s, a consortium formed to develop the Open eBook format as a way for authors and publishers to provide a single source-document which many book-reading software and hardware platforms could handle. Open eBook as defined required subsets of XHTML and CSS; a set of multimedia formats (others could be used, but there must also be a fallback in one of the required formats), and an XML schema for a "manifest", to list the components of a given e-book, identify a table of contents, cover art, and so on. This format led to the open format EPUB. Google Books has converted many public domain works to this open format.In 2010, e-books continued to gain in their own specialist and underground markets.Many e-book publishers began distributing books that were in the public domain. At the same time, authors with books that were not accepted by publishers offered their works online so they could be seen by others. Unofficial (and occasionally unauthorized) catalogs of books became available on the web, and sites devoted to e-books began disseminating information about e-books to the public. Nearly two-thirds of the U.S. Consumer e-book publishing market are controlled by the "Big Five". The "Big Five" publishers include: Hachette, HarperCollins, Macmillan, Penguin Random House and Simon & Schuster.

Libraries

US Libraries began providing free e-books to the public in 1998 through their websites and associated services, although the e-books were primarily scholarly, technical or professional in nature, and could not be downloaded. In 2003, libraries began offering free downloadable popular fiction and non-fiction e-books to the public, launching an E-book lending model that worked much more successfully for public libraries. The number of library e-book distributors and lending models continued to increase over the next few years. From 2005 to 2008 libraries experienced 60% growth in e-book collections. In 2010, a Public Library Funding and Technology Access Study found that 66% of public libraries in the US were offering e-books, and a large movement in the library industry began seriously examining the issues related to lending e-books, acknowledging a tipping point of broad e-book usage.However, some publishers and authors have not endorsed the concept of electronic publishing, citing issues with user demand, copyright piracy and challenges with proprietary devices and systems. In a survey of interlibrary loan librarians it was found that 92% of libraries held e-books in their collections and that 27% of those libraries had negotiated interlibrary loan rights for some of their e-books. This survey found significant barriers to conducting interlibrary loan for e-books.Demand-driven acquisition (DDA) has been around for a few years in public libraries, which allows vendors to streamline the acquisition process by offering to match a library's selection profile to the vendor's e-book titles. The library's catalog is then populated with records for all the e-books that match the profile. The decision to purchase the title is left to the patrons, although the library can set purchasing conditions such as a maximum price and purchasing caps so that the dedicated funds are spent according to the library's budget. The 2012 meeting of the Association of American University Presses included a panel on patron-drive acquisition (PDA) of books produced by university presses based on a preliminary report by Joseph Esposito, a digital publishing consultant who has studied the implications of PDA with a grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation.

Challenges

Although the demand for e-book services in libraries has grown in the decades of the 2000s and 2010s, difficulties keep libraries from providing some e-books to clients. Publishers will sell e-books to libraries, but they only give libraries a limited license to the title in most cases. This means the library does not own the electronic text but that they can circulate it either for a certain period of time or for a certain number of check outs, or both. When a library purchases an e-book license, the cost is at least three times what it would be for a personal consumer. E-book licenses are more expensive than paper-format editions because publishers are concerned that an e-book that is sold could theoretically be read and/or checked out by a huge number of users, which could adversely affect sales.Archival storage

The Internet Archive and Open Library offer over 6,000,000 fully accessible public domain e-books. Project Gutenberg has over 52,000 freely available public domain e-books.Dedicated hardware readers and mobile software

An e-reader, also called an e-book reader or e-book device, is a mobile electronic device that is designed primarily for the purpose of reading e-books and digital periodicals. An e-reader is similar in form, but more limited in purpose than a tablet. In comparison to tablets, many e-readers are better than tablets for reading because they are more portable, have better readability in sunlight and have longer battery life. In July 2010, online bookseller Amazon.com reported sales of e-books for its proprietary Kindle outnumbered sales of hardcover books for the first time ever during the second quarter of 2010, saying it sold 140 e-books for every 100 hardcover books, including hardcovers for which there was no digital edition. By January 2011, e-book sales at Amazon had surpassed its paperback sales. In the overall US market, paperback book sales are still much larger than either hardcover or e-book; the American Publishing Association estimated e-books represented 8.5% of sales as of mid-2010, up from 3% a year before. At the end of the first quarter of 2012, e-book sales in the United States surpassed hardcover book sales for the first time.In Canada, The Sentimentalists won the prestigious national Giller Prize. Owing to the small scale of the novel's independent publisher, the book was initially not widely available in printed form, but the e-book edition became the top-selling title for Kobo devices in 2010. Until late 2013, use of an e-reader was not allowed on airplanes during takeoff and landing. In November 2013, the FAA allowed use of e-readers on airplanes at all times if it is in Airplane Mode, which means all radios turned off, and Europe followed this guidance the next month. In 2014, the New York Times predicted that by 2018 e-books will make up over 50% of total consumer publishing revenue in the United States and Great Britain.

Applications

Some of the major book retailers and multiple third-party developers offer free (and in some third-party cases, premium paid) e-reader software applications (apps) for the Mac and PC computers as well as for Android, Blackberry, iPad, iPhone, Windows Phone and Palm OS devices to allow the reading of e-books and other documents independently of dedicated e-book devices. Examples are apps for the Amazon Kindle, Barnes & Noble Nook, iBooks, Kobo eReader and Sony Reader.Until 1979

- ~1949

- Ángela Ruiz Robles patented in Galicia, Spain, the idea of the electronic book, called the Mechanical Encyclopedia.

- Roberto Busa begins planning the Index Thomisticus.

- ~1963

- Doug Engelbart starts the NLS (and later Augment) projects.

- ~1965

- Andries van Dam starts the HES (and later FRESS) projects, with assistance from Ted Nelson, to develop and use electronic textbooks for humanities and in pedagogy.

- 1971

- Michael S. Hart types the US Declaration of Independence into a computer to create the first e-book available on the Internet and launches Project Gutenberg in order to create electronic copies of more books.

- 1978

- The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy radio series launches (novel published in 1979), featuring an electronic reference book containing all knowledge in the Galaxy. This vast amount of data could be fit into something the size of a large paperback book, with updates received over the "Sub-Etha".

- ~1979

- Roberto Busa finishes the Index Thomisticus, a complete lemmatisation of the 56 printed volumes of Saint Thomas Aquinas and of a few related authors.

1980–99

- 1986

- Judy Malloy wrote and programmed Uncle Roger, the first online hypertext fiction with links that took the narrative in different directions depending on the reader's choice.

- 1989

- Project Gutenberg releases its 10th e-book to its website.

- Franklin Computer released an electronic edition of the Bible that was read on a stand-alone device.

- 1990

- Eastgate Systems publishes the first hypertext fiction released on floppy disk, "Afternoon, a story", by Michael Joyce.

- Electronic Book Technologies releases DynaText, the first SGML-based system for delivering large-scale books such as aircraft technical manuals. It was later tested on a US aircraft carrier as replacement for paper manuals.

- 1991

- Voyager Company develops Expanded Books, which are books on CD-ROM in a digital format.

- 1992

- F. Crugnola and I. Rigamonti design and create the first e-reader, called Incipit, as a thesis project at the Polytechnic University of Milan.

- Sony launches the Data Discman e-book player.

- 1993

- Peter James published his novel Host on two floppy disks and at the time it was called the "world's first electronic novel"; a copy of it is stored at the Science Museum.

- Hugo Award and Nebula Award nominee works are included on a CD-ROM by Brad Templeton.

- Bibliobytes, a website for obtaining e-books, both for free and for sale on the Internet, launches.

- 1994

- C & M Online is founded in Raleigh, North Carolina and publishes e-books through its imprint, Boson Books. Authors include Fred Chappell, Kelly Cherry, Leon Katz, Richard Popkin, and Robert Rodman.

- The popular format for publishing e-books changed from plain text to HTML.

- 1995

- Online poet Alexis Kirke discusses the need for wireless internet electronic paper readers in his article "The Emuse".

- 1996

- Project Gutenberg reaches 1,000 titles.

- Joseph Jacobson works at MIT to create electronic ink, a high-contrast, low-cost, read/write/erase medium to display e-books.

- 1997

- E Ink Corporation is co-founded in 1997 by MIT undergraduates J.D. Albert, Barrett Comiskey, MIT professor Joseph Jacobson, as well as Jeremy Rubin and Russ Wilcox to create an electronic printing technology. This technology is later used to on the displays of the Sony Reader, Barnes & Noble Nook, and Amazon Kindle.

- 1998

- NuroMedia released the first handheld e-reader, the Rocket eBook.

- SoftBook launched its SoftBook reader. This e-reader, with expandable storage, could store up to 100,000 pages of content, including text, graphics and pictures.

- The Cybook was sold and manufactured at first by Cytale (1998–2003) and later by Bookeen.

- 1999

- The NIST released the Open eBook format based on XML to the public domain, most future e-book formats derive from Open eBook. and on XML.

- Publisher Simon & Schuster created a new imprint called ibooks and became the first trade publisher to simultaneously to publish some of their titles in e-book and print format.

- Oxford University Press offered a selection of its books available as e-books through netLibrary.

- Publisher Baen Books opens up the Baen Free Library to make available Baen titles as free e-books.

- Kim Blagg, via her company Books OnScreen, began selling multimedia-enhanced e-books on CDs through retailers including Amazon, Barnes & Noble and Borders Books.

2000s[edit]

- 2000

- Joseph Jacobson, Barrett O. Comiskey and Jonathan D. Albert are granted US patents related to displaying electronic books, these patents are later used in the displays for most e-readers.

- Stephen King releases his novella Riding the Bullet exclusively online and it became the first mass-market e-book, selling 500,000 copies in 48 hours.

- Microsoft releases the Microsoft Reader with ClearType for increased readability on PCs and handheld devices.

- Microsoft and Amazon worked together to sell e-books that could be purchased on Amazon and using Microsoft software downloaded to PCs and handhelds.

- A digitized version of the Gutenberg Bible was made available online at the British Library.

- 2001

- Adobe releases Adobe Acrobat Reader 5.0 allowing users to underline, take notes and bookmark.

- 2002

- Palm, Inc and OverDrive, Inc make Palm Reader e-books available worldwide and offered over 5,000 e-books in several languages; these could be read on Palm PDAs or using a computer application.

- Random House and HarperCollins start to sell digital versions of their titles in English.[citation needed]

- 2004

- Sony Librie, first e-reader using an E Ink display was released; it had a six-inch screen.

- Google announces plans to digitize the holdings of several major libraries, as part of what would later be called the Google Books Library Project.

- 2005

- Amazon buys Mobipocket, the creator of the mobi e-book file format and e-reader software.

- Google is sued for copyright infringement by the Authors Guild for scanning books still in copyright.

- 2006

- Sony Reader PRS-500 with an E Ink screen and two weeks of battery life was released.

- LibreDigital launched BookBrowse as an online reader for publisher content.

- 2007

- The International Digital Publishing Forum releases EPUB to replace Open eBook.

- Amazon.com releases the Kindle e-reader with 6-inch E Ink screen in the US and it sells outs in 5.5 hours.

- Simultaneously with the Kindle in November, the Kindle Store opened that initially had more than 88,000 e-books available.

- Bookeen launches Cybook Gen3 in Europe, it could display e-books and play audiobooks.

- 2008

- Adobe and Sony agree to share their technologies (Adobe Reader and DRM) with each other.

- Sony sells the Sony Reader PRS-505 in UK and France.

- BooksOnBoard becomes first retailer to sell e-books for iPhones.

- 2009

- Bookeen releases the Cybook Opus in the US and in Europe.

- Sony releases the Reader Pocket Edition and Reader Touch Edition.

- Amazon releases the Kindle 2 that included a text-to-speech feature.

- Amazon releases the Kindle DX that had a 9.7-inch screen in the US.

- Barnes & Noble releases the Nook e-reader in the US.

- Amazon released the Kindle for PC application in late 2009, making the Kindle Store library available for the first time outside Kindle hardware.

2010s

- 2010

- In January 2010, Amazon releases the Kindle DX International Edition worldwide.

- Bookeen reveals the Cybook Orizon at CES.

- Apple releases the iPad bundled with an e-book app called iBooks.

- Kobo Inc. releases its Kobo eReader to be sold at Indigo/Chapters in Canada and Borders in the United States.

- Amazon reports that its e-book sales outnumbered sales of hardcover books for the first time ever during the second quarter of 2010.

- Amazon releases the third generation Kindle, available in Wi-Fi and 3G & Wi-Fi versions.

- Kobo Inc. releases an updated Kobo eReader, which included Wi-Fi.

- Barnes & Noble releases the Nook Color, a color LCD tablet.

- Google launches Google eBooks offering over 3 million titles, becoming the world's largest e-book store at that time.

- PocketBook expands its line with an Android e-reader.

- 2011

- Amazon.com announces in May that its e-book sales in the US now exceed all of its printed book sales.

- Barnes & Noble releases the Nook Simple Touch e-reader and Nook Tablet.

- Bookeen launches its own e-books store, BookeenStore.com, and starts to sell digital versions of titles in French.

- Nature Publishing publishes Principles of Biology, a customizable, modular textbook, with no corresponding paper edition.

- The e-reader market grows in Spain, and companies like Telefónica, Fnac, and Casa del Libro launches their e-readers with the Spanish brand "bq readers".

- Amazon launches the Kindle Fire and Kindle Touch; both devices were designed for e-reading.

- 2012

- E-books sold in the U.S. market collects over three billion in revenue.

- Kbuuk released the cloud-based e-book self-publishing SaaS platform on the Pubsoft digital publishing engine.

- Apple releases iBooks Author, software for creating iPad e-books to be directly published in its iBooks bookstore or to be shared as PDF files.

- Apple opens a textbook section in its iBooks bookstore.

- Library.nu - previously called ebooksclub.org and gigapedia.com, a popular linking website for downloading e-books - was accused of copyright infringement and shut down by court order on February 15.

- The publishing companies Random House, Holtzbrinck, and arvato get an e-book library called Skoobe on the market.

- US Department of Justice prepares anti-trust lawsuit against Apple, Simon & Schuster, Hachette Book Group, Penguin Group, Macmillan, and HarperCollins, alleging collusion to increase the price of books sold on Amazon.

- PocketBook releases the PocketBook Touch, an E Ink Pearl e-reader, winning awards from German magazines Tablet PC and Computer Bild.

- In September, Amazon releases the Kindle Paperwhite, its first e-reader with built-in front LED lights.

- 2013

- In April 2013, Barnes & Noble posts losses of $475 million on its Nook business for the prior fiscal year and in June announces its intention to discontinue manufacturing Nook tablets, although it plans to continue making and designing black-and-white e-readers such as the Nook Simple Touch, which "are more geared to serious readers, who are its customers, than to tablets".

- The Association of American Publishers announces that e-books now account for about 20% of book sales. Barnes & Noble estimates it has a 27% share of the U.S. e-book market.

- In June, Apple executive Keith Moerer testifies in the e-book price fixing trial that the iBookstore held approximately 20% of the e-book market share in the United States within the months after launch - a figure that Publishers Weekly reports is roughly double many of the previous estimates made by third parties. Moerer further testified that iBookstore acquired about an additional 20% by adding Random House in 2011.

- Five major US e-book publishers, as part of their settlement of a price-fixing suit, were ordered to refund about $3 for every electronic copy of a New York Times best-seller that they sold from April 2010 to May 2012.This could equal $160 million in settlement charges.

- Barnes & Noble releases the Nook Glowlight, which has a 6-inch touchscreen using E Ink Pearl and Regal, with built-in front LED lights.

- In April, Kobo released the Kobo Aura HD with a 6.8-inch screen, which is larger than the current models produced by its US competitors.

- In May, Mofibo launched the first Scandinavian unlimited access e-book subscription service.

- In July, US District Court Judge Denise Cote finds Apple guilty of conspiring to raise the retail price of e-books and schedules a trial in 2014 to determine damages.

- In August, Kobo released the Kobo Aura, a baseline touchscreen six-inch e-reader.

- In September, Oyster launches its unlimited access e-book subscription service.

- In November, US District Judge Chin sides with Google in Authors Guild v. Google, citing fair use. The authors said they would appeal.

- In December, Scribd launched the first public unlimited access subscription service for e-books.

- 2014

- In early 2014, Amazon launches Kindle Unlimited as an unlimited-access e-book and audiobook subscription service.

- In April, Kobo released the Aura H₂0, the world's first waterproof commercially produced e-reader.

- In June, US District Court Judge Cote grants class action certification to plaintiffs in a lawsuit over Apple's alleged e-book price conspiracy; the plaintiffs are seeking $840 million in damages. Apple appeals the decision.

- In June, Apple settles the e-book antitrust case that alleged Apple conspired to e-book price fixing out of court with the States; however if Judge Cote's ruling is overturned in appeal the settlement would be reversed.

- 2015

- In June 2015, the 2nd US Circuit Court of Appeals with a 2-1 vote concurs with Judge Cote that Apple conspired to e-book price fixing and violated federal antitrust law. Apple appealed the decision.

- In June, Amazon released the Kindle Paperwhite (3rd generation) that is the first e-reader to feature Bookerly, a font exclusively designed for e-readers.

- In September, Oyster announced its unlimited access e-book subscription service would be shut down in early 2016 and that it would be acquired by Google.

- In September, Malaysian e-book company, e-Sentral, introduced for the first time geo-location distribution technology for e-books via bluetooth beacon. It was first demonstrated in a large scale at Kuala Lumpur International Airport.

- In October, Amazon releases the Kindle Voyage that has a 6-inch, 300 ppi E Ink Carta HD display, which was the highest resolution and contrast available in e-readers as of 2014. It also features adaptive LED lights and page turn sensors on the sides of the device.

- In October, B&N released the Glowlight Plus, its first waterproof e-reader.

- In October, the US appeals court sided with Google instead of the Authors' Guild, declaring that Google did not violate copyright law in its book scanning project.

- In December, Playster launched an unlimited-access subscription service including e-books and audiobooks.

- By the end of 2015, Google Books scanned more than 25 million books.

- By 2015, over 70 million e-readers had been shipped worldwide.

- 2016

- In March 2016, the Supreme Court of the United States declined to hear Apple's appeal that it conspired to e-book price fixing therefore the previous court decision stands, which means Apple must pay $450 million.

- In April, the Supreme Court declined to hear the Authors Guild's appeal of its book scanning case that means the lower court's decision stands; this result means Google is allowed to scan library books and display snippets in search results without violating US copyright law.

- In April, Amazon released the Kindle Oasis, its first e-reader in five years to have physical page turn buttons and as a premium product includes a leather case with a battery inside; the Oasis without including the case is the lightest e-reader on the market.

- In August, Kobo released the Aura One, the first commercial e-reader with a 7.8-inch E Ink Carta HD display.

- By the end of 2016, smartphones and tablets both individually overtook e-readers for ways to read an e-book, and paperbook books sales were higher than e-book sales.

- 2017

- In February 2017, the Association of American Publishers released data that shows the U.S. adult e-book market declined 16.9% in the first nine months of 2016 over the same time in 2015 and Nielsen Book determined that in 2016 the e-book market had an overall total decline of 16% in 2016 over 2015, including all age groups. This decline is partly due to widespread e-book price increases by major publishers, which brought the average price from $6 to nearly $10.

- In March, The Guardian reported that sales of physical books outperform digital titles in the UK, since it can be cheaper to buy the physical version of a book when compared to the digital version due to Amazon's deal with publishers that allows agency pricing.

- In April, it was reported that the 2016 sales of hardcover books were higher than e-books for the first time in five years.

Formats

Writers and publishers have many formats to choose from when publishing e-books. Each format has advantages and disadvantages. The most popular e-readers and their natively supported formats are shown below:| Reader | Native e-book formats |

|---|---|

| Amazon Kindle and Fire tablets | AZW, AZW3, KF8, non-DRM MOBI, PDF, PRC, TXT |

| Barnes & Noble Nook and Nook Tablet | EPUB, PDF |

| Apple iPad | EPUB, IBA (Multitouch books made via iBooks Author), PDF |

| Sony Reader | EPUB, PDF, TXT, RTF, DOC, BBeB |

| Kobo eReader and Kobo Arc | EPUB, PDF, TXT, RTF, HTML, CBR (comic), CBZ (comic) |

| PocketBook Reader and PocketBook Touch | EPUB DRM, EPUB, PDF DRM, PDF, FB2, FB2.ZIP, TXT, DJVU, HTM, HTML, DOC, DOCX, RTF, CHM, TCR, PRC (MOBI) |

Digital rights management

Most e-book publishers do not warn their customers about the possible implications of the digital rights management tied to their products. Generally, they claim that digital rights management is meant to prevent illegal copying of the e-book. However, in many cases, it is also possible that digital rights management will result in the complete denial of access by the purchaser to the e-book.The e-books sold by most major publishers and electronic retailers, which are Amazon.com, Google, Barnes & Noble, Kobo Inc. and Apple Inc., are DRM-protected and tied to the publisher's e-reader software or hardware. The first major publisher to omit DRM was Tor Books, one of the largest publishers of science fiction and fantasy, in 2012. Smaller e-book publishers such as O'Reilly Media, Carina Press and Baen Books had already forgone DRM previously.Production

Some e-books are produced simultaneously with the production of a printed format, as described in electronic publishing, though in many instances they may not be put on sale until later. Often, e-books are produced from pre-existing hard-copy books, generally by document scanning, sometimes with the use of robotic book scanners, having the technology to quickly scan books without damaging the original print edition. Scanning a book produces a set of image files, which may additionally be converted into text format by an OCR program. Occasionally, as in some projects, an e-book may be produced by re-entering the text from a keyboard. Sometimes only the electronic version of a book is produced by the publisher. It is possible to release an e-book chapter by chapter as each chapter is written. This is useful in fields such as information technology where topics can change quickly in the months that it takes to write a typical book. It is also possible to convert an electronic book to a printed book by print on demand. However, these are exceptions as tradition dictates that a book be launched in the print format and later if the author wishes an electronic version is produced. The New York Times keeps a list of best-selling e-books, for both fiction and non-fiction.Reading data

All of the e-readers and reading apps are capable of tracking e-book reading data, and the data could contain which e-books users open, how long the users spend reading each e-book and how much of each e-book is finished. In December 2014, Kobo released e-book reading data collected from over 21 million of its users worldwide. Some of the results were that only 44.4% of UK readers finished the bestselling e-book The Goldfinch and the 2014 top selling e-book in the UK, "One Cold Night", was finished by 69% of readers; this is evidence that while popular e-books are being completely read, some e-books are only sampled.Comparison to printed books

Advantages

iLiad e-book reader equipped with an e-paper display visible in sunlight

Printed books use three times more raw materials and 78 times more water to produce when compared to e-books. While an e-reader costs more than most individual books, e-books may have a lower cost than paper books. E-books may be printed for less than the price of traditional books using on-demand book printers. Moreover, numerous e-books are available online free of charge on sites such as Project Gutenberg. For example, all books printed before 1923 are in the public domain, which means its free to obtain e-book versions of them.

Depending on possible digital rights management, e-books (unlike physical books) can be backed up and recovered in the case of loss or damage to the device on which they are stored, a new copy can be downloaded without incurring an additional cost from the distributor, as well as being able to synchronize the reading location, highlights and bookmarks across several devices.

Downsides

There may be a lack of privacy for the user's e-book reading activities; for example, Amazon knows the user's identity, what the user is reading, whether the user has finished the book, what page the user is on, how long the user has spent on each page, and which passages the user may have highlighted. One obstacle to wide adoption of the e-book is that a large portion of people value the printed book as an object itself, including aspects such as the texture, smell, weight and appearance on the shelf. Print books are also considered valuable cultural items, and symbols of liberal education and the humanities.Kobo found that 60% of e-books that are purchased from their e-book store are never opened and found that the more expensive the book is, the more likely the reader would at least open the e-book.Joe Queenan has written about the pros and cons of e-books:

Electronic books are ideal for people who value the information contained in them, or who have vision problems, or who like to read on the subway, or who do not want other people to see how they are amusing themselves, or who have storage and clutter issues, but they are useless for people who are engaged in an intense, lifelong love affair with books. Books that we can touch; books that we can smell; books that we can depend on.While a paper book is vulnerable to various threats, including water damage, mold and theft, e-books files may be corrupted, deleted or otherwise lost as well as pirated. Where the ownership of a paper book is fairly straightforward (albeit subject to restrictions on renting or copying pages, depending on the book), the purchaser of an e-book's digital file has conditional access with the possible loss of access to the e-book due to digital rights management provisions, copyright issues, the provider's business failing or possibly if user's credit card expired.

United States

In 2015, the Author Earnings Report estimated that Amazon held a 74% market share of the e-books sold in the U.S.] By the end of 2016, that year's Report estimated that Amazon held 80% of the e-book market share in the U.S.Canada

Spain

In 2013, Carrenho estimates that e-books would have a 15% market share in Spain in 2015.UK

According to Nielsen Book Research, e-book share went from 20% to 33% between 2012 and 2014, but down to 29% in the first quarter of 2015. Amazon-published and self-published titles accounted for 17 million of those books - worth £58m – in 2014, representing 5% of the overall book market and 15% of the digital market. The volume and value sales are similar to 2013 but up 70% since 2012.Germany

The Wischenbart Report 2015 estimates the e-book market share to be 4.3%.Brazil

The Brazilian e-book market is only emerging. Brazilians are technology savvy, and that attitude is shared by the government. In 2013, around 2.5% of all trade titles sold were in digital format. This was a 400% growth over 2012 when only 0.5% of trade titles were digital. In 2014, the growth was slower, Brazil had 3.5% of its trade titles being sold as e-books.China

The Wischenbart Report 2015 estimates the e-book market share to be around 1%.X . IIIIII

Online book

Online books are a common resource in virtual learning environments (VLEs). For example, the Moodle VLE defines an online book in this way. Over the last few years, there has been an increase of online books that are being used for notable events or to commemorate the memory of someone. The fundraising industry often uses online books as a way to fundraise, as online books are also a way to collect donations and engage with their audience .

Electronic journals, also known as ejournals, e-journals, and electronic serials, are scholarly journals or intellectual magazines that can be accessed via electronic transmission. Some journals are 'born digital' in that they are solely published on the web and in a digital format, but most electronic journals originated as print journals, which subsequently evolved to have an electronic version, while still maintaining a print component. As academic research habits have changed in line with the growth of the internet, the e-journal has come to dominate the journals world.

An e-journal closely resembles a print journal in structure: there is a table of contents which lists the articles, and many electronic journals still use a volume/issue model, although some titles now publish on a continuous basis. Online journal articles are a specialized form of electronic document: they have the purpose of providing material for academic research and study, and they are formatted approximately like journal articles in traditional printed journals. Often a journal article will be available for download in two formats - as a PDF and in HTML format, although other electronic file types are often supported for supplementary material. Articles are indexed in bibliographic databases, as well as by search engines. E-journals allow new types on content to be included in journals, for example video material, or the data sets on which research has been based.

With the growth and development of the internet, there has been a growth in the number of new journals, especially in those that exist as digital publications only. A subset of these journals exist as Open Access titles, meaning that they are free to access for all, and have Creative Commons licences which permit the reproduction of content in different ways. High quality open access journals are listed in Directory of Open Access Journals. Most however continue to exist as subscription journals, for which libraries, organisations and individuals purchase access

Academic publishing is the subfield of publishing which distributes academic research and scholarship. Most academic work is published in academic journal article, book or thesis form. The part of academic written output that is not formally published but merely printed up or posted on the Internet is often called "grey literature". Most scientific and scholarly journals, and many academic and scholarly books, though not all, are based on some form of peer review or editorial refereeing to qualify texts for publication. Peer review quality and selectivity standards vary greatly from journal to journal, publisher to publisher, and field to field.

Most established academic disciplines have their own journals and other outlets for publication, although many academic journals are somewhat interdisciplinary, and publish work from several distinct fields or subfields. There is also a tendency for existing journals to divide into specialized sections as the field itself becomes more specialized. Along with the variation in review and publication procedures, the kinds of publications that are accepted as contributions to knowledge or research differ greatly among fields and subfields.

Academic publishing is undergoing major changes, as it makes the transition from the print to the electronic format. Business models are different in the electronic environment. Since the early 1990s, licensing of electronic resources, particularly journals, has been very common. Currently, an important trend, particularly with respect to journals in the sciences, is open access via the Internet. In open access publishing, a journal article is made available free for all on the web by the publisher at the time of publication. It is typically made possible after the author pays hundreds or thousands of dollars in publication fees, thereby shifting the costs from the reader to the researcher or their funder. The Internet has facilitated open access self-archiving, in which authors themselves make a copy of their published articles available free for all on the web

In academic publishing, a paper is an academic work that is usually published in an academic journal. It contains original research results or reviews existing results. Such a paper, also called an article, will only be considered valid if it undergoes a process of peer review by one or more referees (who are academics in the same field) who check that the content of the paper is suitable for publication in the journal. A paper may undergo a series of reviews, revisions, and re-submissions before finally being accepted or rejected for publication. This process typically takes several months. Next, there is often a delay of many months (or in some subjects, over a year) before an accepted manuscript appears. This is particularly true for the most popular journals where the number of accepted articles often outnumbers the space for printing. Due to this, many academics self-archive a 'pre-print' copy of their paper for free download from their personal or institutional website.

Some journals, particularly newer ones, are now published in electronic form only. Paper journals are now generally made available in electronic form as well, both to individual subscribers, and to libraries. Almost always these electronic versions are available to subscribers immediately upon publication of the paper version, or even before; sometimes they are also made available to non-subscribers, either immediately (by open access journals) or after an embargo of anywhere from two to twenty-four months or more, in order to protect against loss of subscriptions. Journals having this delayed availability are sometimes called delayed open access journals. Ellison has reported that in economics the dramatic increase in opportunities to publish results online has led to a decline in the use of peer-reviewed articles

Publishing process

The process of academic publishing, which begins when authors submit a manuscript to a publisher, is divided into two distinct phases: peer review and production.The process of peer review is organized by the journal editor and is complete when the content of the article, together with any associated images or figures, are accepted for publication. The peer review process is increasingly managed online, through the use of proprietary systems, commercial software packages, or open source and free software. A manuscript undergoes one or more rounds of review; after each round, the author(s) of the article modify their submission in line with the reviewers' comments; this process is repeated until the editor is satisfied and the work is accepted.

The production process, controlled by a production editor or publisher, then takes an article through copy editing, typesetting, inclusion in a specific issue of a journal, and then printing and online publication. Academic copy editing seeks to ensure that an article conforms to the journal's house style, that all of the referencing and labelling is correct, and that the text is consistent and legible; often this work involves substantive editing and negotiating with the authors. Because the work of academic copy editors can overlap with that of authors' editors, editors employed by journal publishers often refer to themselves as “manuscript editors”.

In much of the 20th century, such articles were photographed for printing into proceedings and journals, and this stage was known as camera-ready copy. With modern digital submission in formats such as PDF, this photographing step is no longer necessary, though the term is still sometimes used.

The author will review and correct proofs at one or more stages in the production process. The proof correction cycle has historically been labour-intensive as handwritten comments by authors and editors are manually transcribed by a proof reader onto a clean version of the proof. In the early 21st century, this process was streamlined by the introduction of e-annotations in Microsoft Word, Adobe Acrobat, and other programs, but it still remained a time-consuming and error-prone process. The full automation of the proof correction cycles has only become possible with the onset of online collaborative writing platforms, such as Authorea, Google Docs, and various others, where a remote service oversees the copy-editing interactions of multiple authors and exposes them as explicit, actionable historic events

Scientific, technical, and medical (STM) literature is a large industry which generated $23.5 billion in revenue; $9.4 billion of that was specifically from the publication of English-language scholarly journals. Most scientific research is initially published in scientific journals and considered to be a primary source. Technical reports, for minor research results and engineering and design work (including computer software), round out the primary literature. Secondary sources in the sciences include articles in review journals (which provide a synthesis of research articles on a topic to highlight advances and new lines of research), and books for large projects, broad arguments, or compilations of articles. Tertiary sources might include encyclopedias and similar works intended for broad public consumption or academic libraries.

A partial exception to scientific publication practices is in many fields of applied science, particularly that of U.S. computer science research. An equally prestigious site of publication within U.S. computer science are some academic conferences. Reasons for this departure include a large number of such conferences, the quick pace of research progress, and computer science professional society support for the distribution and archiving of conference proceedings.

In recent decades there has been a growth in academic publishing in developing countries as they become more advanced in science and technology. Although the large majority of scientific output and academic documents are produced in developed countries, the rate of growth in these countries has stabilized and is much smaller than the growth rate in some of the developing countries. The fastest scientific output growth rate over the last two decades has been in the Middle East and Asia with Iran leading with an 11-fold increase followed by the Republic of Korea, Turkey, Cyprus, China, and Oman. In comparison, the only G8 countries in top 20 ranking with fastest performance improvement are, Italy which stands at tenth and Canada at 13th globally.

By 2004, it was noted that the output of scientific papers originating from the European Union had a larger share of the world's total from 36.6 to 39.3 percent and from 32.8 to 37.5 per cent of the "top one per cent of highly cited scientific papers". However, the United States' output dropped 52.3 to 49.4 per cent of the world's total, and its portion of the top one percent dropped from 65.6 to 62.8 per cent.

Iran, China, India, Brazil, and South Africa were the only developing countries among the 31 nations that produced 97.5% of the most cited scientific articles in a study published in 2004. The remaining 162 countries contributed less than 2.5%. The Royal Society in a 2011 report stated that in share of English scientific research papers the United States was first followed by China, the UK, Germany, Japan, France, and Canada. The report predicted that China would overtake the United States sometime before 2020, possibly as early as 2013. China's scientific impact, as measured by other scientists citing the published papers the next year, is smaller although also increasing.

In academic publishing, an eprint or e-print is a digital version of a research document (usually a journal article, but could also be a thesis, conference paper, book chapter, or a book) that is accessible online, whether from a local institutional, or a central (subject- or discipline-based) digital repository.

When applied to journal articles, the term "eprints" covers both preprints (before peer review) and postprints (after peer review).

Digital versions of materials other than research documents are not usually called e-prints, but some other name, such as e-books.

Internet Public Library

The digital collections on the site were divided into five broad categories, and include Resources by Subject, Newspapers & Magazines, Special Collections Created By the ipl2, and Special Collections for Kids and Teens. As of March 2011 it had about 40,000 searchable resources

The IPL originated at the University of Michigan’s School of Information. Michigan SI students almost exclusively generated its content. They also managed the Ask a Question reference service. In 2006 the University of Michigan opened up management of the IPL to other information science and library schools. They stopped hosting the IPL and moved the servers and staff positions to Drexel University, and by January 2007 the "IPL Consortium" that ran the IPL comprised a group of 15 colleges, including the University of Michigan. Drexel's College of Computing and Informatics hosted the site. With a grant from the Institute of Museum and Library Services, Drexel also used the site as a "'technological training center' for digital librarians."

In 2009 the Internet Public Library merged with the Librarians' Internet Index, a publicly funded website that until then was managed by the Califa Library group; the new web presence, which continued to be hosted by Drexel University, was dubbed "ipl2".

According to Dr. Joseph Janes, ipl2 would no longer be supported as of the end of 2014. The last ipl2 monthly newsletter was February 2014. All operations officially ended on June 30, 2015.

The IPL originated at the University of Michigan’s School of Information. Michigan SI students almost exclusively generated its content. They also managed the Ask a Question reference service. In 2006 the University of Michigan opened up management of the IPL to other information science and library schools. They stopped hosting the IPL and moved the servers and staff positions to Drexel University, and by January 2007 the "IPL Consortium" that ran the IPL comprised a group of 15 colleges, including the University of Michigan. Drexel's College of Computing and Informatics hosted the site. With a grant from the Institute of Museum and Library Services, Drexel also used the site as a "'technological training center' for digital librarians."

In 2009 the Internet Public Library merged with the Librarians' Internet Index, a publicly funded website that until then was managed by the Califa Library group; the new web presence, which continued to be hosted by Drexel University, was dubbed "ipl2".

According to Dr. Joseph Janes, ipl2 would no longer be supported as of the end of 2014. The last ipl2 monthly newsletter was February 2014. All operations officially ended on June 30, 2015.

Scope

ipl2's Mission Statement and Vision Statement, adopted 19 May 2008, are:| “ | Mission Statement of ipl2 ipl2 is a global information community that provides in-service learning and volunteer opportunities for library and information science students and professionals, offers a collaborative research forum, and supports and enhances library services through the provision of authoritative collections, information assistance, and information instruction for the public. Vision Statement of ipl2 ipl2 will shape and direct the evolving role of libraries in an increasingly digital world while working to become a virtual learning laboratory for the study of information services and technology. The ipl2 staff, faculty, and volunteers will strive to meet these goals by:

The Internet Public Library was generally highly regarded. It was noted for its "clean design" and depth of resources as well as its reference service that by 2011 had answered more than 100,000 queries.[2] Elimination of site suggestionsIPL has been closed, with regard to website suggestions from outsiders, since 2010. At that time, the site had more than 21,000 suggestions, of which greater than 85% were deemed inappropriate, based on the site's inclusion criteria.XAMPLE ; Digital Public Library of America

OverviewThe DPLA is a discovery tool, or union catalog, for public domain and openly licensed content held by the United States' archives, libraries, museums, and other cultural heritage institutions. It was started by Harvard University's Berkman Center for Internet & Society in 2010, with financial support from the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, and has subsequently received funding from several foundations and government agencies, including the US National Endowment for the Humanities, and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. It "aims to unify such disparate sources as the Library of Congress, the Internet Archive, various academic collections, and presumably any other collection that would be meaningful to include. ... They have yet to ... decide such issues as how near to the present their catalog will come. There is an ongoing dispute regarding so-called 'orphan works' and other questions of copyright." John Palfrey, co-director of the Berkman Center, stated in 2011: "We aspire to establish a system whereby all Americans can gain access to information and knowledge in digital formats in a manner that is 'free to all.' It is by no means a plan to replace libraries, but rather to create a common resource for libraries and patrons of all types.”The DPLA links service hubs, including twelve major state and regional digital libraries or library collaborations, as well as sixteen content hubs that maintain a one-to-one relationship with DPLA. Board of DirectorsIn September, 2012, an inaugural Board of Directors was appointed to guide the DPLA: Cathy Casserly, CEO of Creative Commons; Paul Courant, University Librarian and Dean of Libraries, Harold T. Shapiro Collegiate Professor of Public Policy, Arthur F. Thurnau Professor, Professor of Economics and Professor of Information at the University of Michigan; Laura DeBonis, Former Director of Library Partnerships for Google Book Search; Luis Herrera, City Librarian for the City and County of San Francisco; and John Palfrey, Head of School, Phillips Academy Andover. In 2015, John Palfrey, the founding chairman of the board, was succeeded by Amy Ryan of the Boston Public Library and Jennifer 8. Lee also joined the board.Daniel J. Cohen was appointed as the founding Executive Director in March 2013. | ||||||||||||||

3D printing

3D printing